Workers on the Land: The Grape Strikers in Delano

by Jeff Rudick

Editor’s Preface: In 1970, the year this article was written, the Catholic Worker Farm was in Tivoli, New York, not far from Bard College, a highly regarded liberal arts institution, as it still is. Indeed Bard was close enough for students to walk to the farm, and not only did many do this regularly, but some came to live at the Worker summers and holidays. The poet and theater director Jeffrey Rudick was one such student, and a valuable addition to the community. He was “looking for a project” and Dorothy encouraged him to “get yourself to Delano and write about it for the paper”, as he recalls her saying. The Worker could be said to have “raised the social consciousnesses” of many generations of students, not just those from Bard. JG

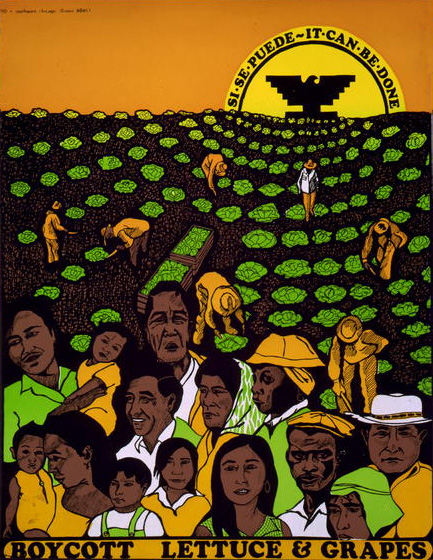

Poster c. 1970, artist unknown; courtesy of University of Michigan

I joined the strikers in Delano, now well into their fifth year of a frustrating battle, for little more than five weeks, and hardly claim to know in a real way what their hardship was. But my impressions from the experience were and are strong and lasting, and I would like to share some of them.

I bussed up from Bakersfield to Delano through the flat commercial roads interspersed with long rows of vines. Delano appeared an ugly flat monotonous town devoid of woodland, crammed with the commercial clutter that plagues the landscape of America. I was later to learn that the railroad, which slices through the town, the planted orange trees and palms, and the long fields of vines on the outskirts were the only pleasing diversions for the eye.

As I sat on the bench in front of the small Greyhound station, I felt increasingly defensive. Many drivers in the traffic I was watching turned their heads and eyed me suspiciously as they passed by. I became conscious of my long hair as in so many small towns; I wondered if they knew I had come to join the strikers. I stepped into the nearest phone booth and leafed through the book for the number of the strikers’ headquarters. It was nearly dark and the last rays of the setting sun were fading, a dark shadow of rusted red becoming more prominent, until, as I reached the U’s there was a large red blotch as of crusted blood over the United Farm Workers’ listing.

Reverend Jim Drake came to pick me up and drove me to Filipino Hall where the strikers took their communal meals. Supper was almost completed and as I ate I met some of the earliest organizers of the strike: Pablo Espinoza, a warm Chicano, Julian Baladoy and Pete Velasco, both Filipinos. When I mentioned to Julian the hostility I sensed from the people as I arrived he smiled patiently and said, “Well, sure, most people in this town have been opposed to our strike from the beginning. Many growers live here, and if you mention the strike to many in Delano they will look at you and say ‘What strike? I didn’t know of any grape strike.’”

After supper Pete Velasco drove another newly arrived volunteer and me to the Filipino Camp. There were two rows of long white clapboard cabins and a mess/recreation hall. Outside the hall two men were turning two lambs on spits over an open fire. Beyond the fire the wind was picking up and chilling a huge dark field of vines. The lights of Delano flickered far off around the rim of the field. I learned there was to be a barbecue as it was Saturday night and strikers would soon be arriving. A man who had been on strike for some time was talking to Pete. I heard Pete tell him, “I know you need the money. If you must go back to work that’s your decision.” With the dark cold wind through the vines these words brought the problem home. Those of us there sat around the fire. I pulled out my guitar and we began singing. Soon I handed the guitar to a warm and melancholy man who said he would like to play. Marcario began playing and singing beautiful Mexican songs, and songs about Zapata, as well as quick and romping and gentle love songs. His voice was thick and emotional; the fire illuminated his face, his eyes closed as he lifted his head to sing. All of us entered into the mood of the songs.

Soon others had arrived and the meat was cooked. We entered the brightly lighted mess hall and began to eat. More and more people entered and the spirit was very high. Soon there was a great deal of laughing, joking, and shouting. As each new group of strike-workers entered they were met with delightfully silly ovations. Everyone would begin a rhythmic clap or pound the table or the floor, and the tempo would increase to a deafening roar until it dissipated in chaos and laughter.

Gallons of their own wine appeared though spirits were high enough without it. Pete turned to me smiling and said, “It is very rare we get to relax like this. It is good to see everyone happy, letting go and having fun. Saturday night is our one night to rest like this.” He and Julian pointed out those who “have been in this struggle since the beginning.” Pete emphasized the good in Filipinos, Chicanos, and Anglos coming together for the common good. “It is beautiful that there is no discrimination here. We are all together and any man is welcome to join us if he will help us.” Pete, Julian, and all the Filipinos very often refer to fellow workers as “brothers”, using the term with great sincerity. The tone in which they say it implies all that it can mean: We must work together.

Guitars appeared and songs burst out spontaneously. Old and young alike pounded tables in rhythm and freely yelled out additions and cries of delight. Then there were brief, fiery speeches; some rhythmic ovations followed these; they follow every speech of spirit and good news at Delano. And always the love of song unifies. Songs went on until guitar strings broke and voices were hoarse. Eventually I walked outside, a bit overwhelmed with the noise. It struck me that first night that there was great optimism and energy, real joy and togetherness, an intense kind of peace, that all this energy and togetherness would have to go somewhere, move something.

In the weeks that followed, I worked in the office of El Malcriado, the union newspaper, and in the headquarters office. As all causes become organized there inevitably arises reams of paperwork, the tasks at times seeming removed from the real issues, which are in the fields—organizing, picketing, communicating—and in the stores of the cities and towns, the boycotting. Delano is the administrative center at this point, but as Chavez said in a meeting, “The action is not in Delano. It is not here that the strike will be won or lost. But there is work here that must be done.” Almost everyone was itching to be “where the action is,” including Chavez himself, I think, but it is important to recognize how much the full-time volunteers put into their work at one remove from the “action” and how little they felt removed.

Of course many who were at Delano that winter had in the past been in the fields, picketing scabs and organizing, and in the cities boycotting. Many women in Delano who once endured the pre-dawn hardships of picketing now cringe at the word. But there is the pervasive attitude in Delano that all work for the strike is important, that without the newspaper to publicize recent events and information or without the defense fund to bring in the crucial flow of donations, the strike would soon be crippled.

I worked a great deal with Pete Velasco in the defense fund office. Pete, who was once an orange grove foreman, and who was one of the most important early organizers in the fields, had for the previous six months been given charge of the tricky responsibility of bringing in money. Although he longed to be back organizing he had totally committed himself to fundraising. He was meticulous in his work, out of his love and appreciation for all those who donated to the strike. Every donor, no matter how much, had to be thanked and contacted. “People are this strike,” he said. “It is people like these who keep it going, bring food to our table and provide the expense money for our boycotters and organizers. These people must know that we are here, and that we thank them and depend on them to go on. These letters are a river and the river must keep flowing.”

The full time strikers at Delano were given five dollars a week spending money. The union provided meals at the Filipino Hall, rent for those who could not meet it and medical expenses. There was a cooperative gas station with discounts for strikers and a clinic begun by the Ladies’ Garment Workers Union volunteers. But, needless to say, for everyone funds were tight and necessities had to suffice.

United Farm Workers at Safeway store, Feb. 1973; photographer unknown; courtesy UFW

A volunteer is given a room in one of the strikers’ homes. Though it was known I could stay only two months, from the first night on I was made to feel at home and felt I was part of the community. While in Delano, I felt there was a change coming, some new turn of tactic to be resolved and enacted. There was a general feeling that the boycott had not been successful enough, that there had not been enough of a nationwide drop in grape sales from 1968 to 1969. The growers were hurt through loss of sales, grapes rotting in cold storage, a significant drop in the selling per lug, and legal expenses from the union’s lawsuits. They had lost well over fifteen million dollars, but they were still making 80 million a year. The growers must feel the impact of the strike’s publicity as they are spending millions of dollars with Whitaker-Baxter and other public relations firms to oppose the strike. The strike has been hurting them but is it enough to win? According to a recent article in El Malcriado, “Grape growers began 1970 with over 6,000,000 boxes of unsold grapes remaining from the 1969 season.” The article continues to note that all of the top ten cities show a decline in grape sales since 1966 with the exception of Montreal. Outside of nine rather “low consumption” cities, which have increased sales, every major U.S. and Canadian city has shown a drop in sales. Some cities have dropped significantly, as in the three largest cities: New York dropped 769 carload rates in 1969 from its 2294 in 1966, Chicago dropped 448 from its 1084, and L.A. dropped 354 from its 2161 in 1966.

Larry Itliong was the boycott director. He also noted in the same El Malcriado article the importance of the price drop in grapes. He said, “Emperors, the main variety of grapes left in cold storage, are selling at $2.50 a lug, a drop of 38 cents from the price at this time last year. Ribiers are selling at $2.50 a lug, a drop of $1.25. Calmerias are selling at $2.38, a drop of $1.50. All these prices have been declining. When they try to unload the 4,300,000 boxes of unsold Emperors, 700,000 boxes of unsold Ribiers, and 600,000 boxes of unsold Calmerias on the market, those prices will drop even further. They are in real trouble.”

The implication is that it was important to intensify the boycott. “If we can block the sale of these grapes, and shut off more markets to the 1970 harvest which begins in May, then the growers will simply have to sit down at the table and work out an agreement with their workers to end the boycott.”

The impetus of the boycott had been seriously interrupted and impeded twice before in the past: once before 1968 when the growers diverted the effort by a pretense of negotiations, and in 1968 when the defense department suddenly ordered huge shipments of unsold grapes for the army’s consumption. The impetus of the boycott was becoming stronger, and the defense department’s purchase was a crucial blow to a possible breakthrough. The union was especially concerned to prevent such diversions from impeding the intensity of the boycott again.

As I mentioned before, there was a sense of change afoot in Delano the first two weeks I was there in January, a kind of unspoken tension and restlessness, which finally surfaced in a special strikers’ meeting at Chavez’s headquarters, Forty Acres. As his back troubled him, Chavez sat in a rocking chair at meetings. He was a bit jumpy, peeved at those who straggled in late, and he was worried about the situation in Delano. He spoke in his usual frank and quiet way about the tensions in the Delano office. People working on the strike had begun to conceal their feelings for and irritations with each other and with him. He looked tired, weary. He said his name was being used as the authority to pass the buck with tasks that had to be done, and that everyone was going to have to start taking more of the workload and responsibilities upon themselves. Everyone was going to have to work longer hours, if necessary, if the strike was to be won. He said, “There’s another thing. Many of us have been talking behind people’s backs. If you’ve got something you’re mad at me for, say it to my face, and I’ll do the same with you. Say it out. Let’s keep these things in the open. If we don’t, we’ll never hold together. If too much anger builds up, we’re in trouble. If a little irritation is concealed, and then the next one is also concealed, before you know it there’s a lot of anger. Let’s get it out in the open every time, before it builds up. We’re going to start doing this. If I say something you don’t approve of, you can kick me out. I’m going to say it, anyway. And I expect the same from you.”

He went on to say that he was upset, not only that there had been no picketing in Delano for over three months, but that no one had even bothered to ask why the action had stopped. He said, “I’m not the only one here who should be worrying about something like this. I can’t run this strike alone. I’m not running it myself. I need you to help me, to give me ideas. I’m an old man already (he smiled shyly at this touch of melodrama). I’m over forty anyway. I want you to know that I think most people are getting things only half-done. Everything has got to be all done, or we’ll lose. The growers aren’t going to help us. I want you all to feel this thing gnawing at your guts, because I’ll tell you, this strike gnaws at mine all the time, and I don’t want to be the only one that feels it. I lose a lot of sleep worrying about how to win this thing. I want you to worry too. I want some ideas. I think we’re floundering here in Delano, like a rudderless ship, placing too much emphasis and time on administrative work, and dividing our emphasis. There are three things we are doing: boycotting, picketing and organizing. But we’re also doing this administrative work here in Delano. It’s important not to divide our energies if we hope to win this strike. I’ve asked Pablo (Espinoza) to immediately set up small discussion groups. I want you to talk this out in these groups, for each group to present a plan to win, and then we’ll have a big meeting, hear the plans, argue them, and vote. One thing’s for sure, if we’re going to win this strike, it won’t be in these offices; it’ll be out in the fields, in the stores, and house to house. The action isn’t here in Delano. The Thompson seedless grapes are going to be picked by late May, and they’ll hit the stores by June. We’ve got to stop those grapes, and if we’re going to, we’ve got to start stopping them now!”

The ice had been broken, and many agreed with Chavez that the energies had been divided, and that a lot of good organizers had been trapped in administrative work at Delano and should get back to the fields as soon as possible, including Chavez himself.

Cesar had asked people to speak their grievances to his face. And out they came, one after another, the charges of half-done jobs and countercharges of misplacement of talent and partial assistance from the top administrators and trusted inner circle. The meeting went on and on, into the afternoon, and the anger was there, the built-up frustration Chavez had sensed so well. But, most importantly, the spirit was there. The anger was constructive once it surfaced. The anger demanded a change of emphasis and harder work from everybody. A change in organization, new and harder tactics were on their way.

The meeting broke up into discussion groups. The consensus issuing from most of them seems to have been that many of the best and most experienced organizers and boycotters who were trapped in the administrative offices should immediately be sent out again to cities around the country, and to the fields in California. The younger volunteers who had the potential to organize and boycott, but who had yet to gain experience, should be sent out also, as many as the office could afford to sacrifice. In the discussion group I attended were Gil Podilla, an experienced bilingual organizer, Pablo Espinoza, the Chicano who organized and moderated the groups of picketers, and Doug Adair, the El Malcriado editor. Gil thought that a skeleton crew could be trained to run the offices in Delano, thus freeing the organizing talent for an activist role. Several positions of crucial importance in the Delano headquarters could never be vacated, of course, such as the ranch and negotiating committees, accounting, and the Legal Department. Pete Velasco would be hard to replace in the Defense Fund; there might be someone such as Leroy Chatfield to handle negotiations, should they arise, and workers’ grievances in the vineyards where there were contracts. As Chatfield pointed out, getting a contract (ten wine growers have now signed) was only the first stage of the battle, because contracts might be and had already been, greatly abused. Therefore, some people talented in organizing and boycotting would inevitably be found indispensable in the Delano office. But many, including Chavez, the best boycott organizer there is, could be freed from administrative work to lead the boycott.

Doug Adair spoke up. He wanted to see a fully organized strike in the Coachela Valley, where one was almost successful in 1968. A strike in Coachela, if successfully securing a contract and wage rise, would break ground for a larger successful strike in Delano and set a precedent for other workers to demand equal concessions and rights. All agreed that picketing and organizing in Delano at this point is fruitless, for the resistance had been too great there, and the only chance would be a resumption of house to house organizing, person to person, night and day, which hasn’t been done in Delano for years. Gil disagreed strongly with Doug. He said, “In Delano we were afraid of the cops. I couldn’t get pickets out. I could convince people to walk out of the fields, but for how long? I’m not going to promise them food and money.” This seems to be the crux of the problem. Gil was saying that even if organizers can clear a field completely of grape-pickers, in a day or two the growers will be able to import scabs from Mexico and the fields are full again. The misuse of the “green card visa” allows a steady flow of Mexican migrants to enter the states at harvest time. Though the wages are low to Americans, they are worth twelve times in Mexico what they are here. The Filipinos are afraid to quit their jobs and see Chicanos take their places. There has been some success at turning Mexicans back at the border, by explaining the strike to them. A radio station has begun broadcasting the facts of the strike across the border from Calexico. But Gil’s point was that unless they, as a group, agree not to scab, a fully successful strike is impossible. Therefore, Gil’s conclusion was that the boycott was the only winning tactic. “Thompson grapes are going to get picked anyway,” he admitted, “so let’s get out and stop them before they hit the stores.”

A proposed piece of legislation called the Murphy Bill was attempting to declare the boycott illegal because it interfered with the consumer’s choice to buy or not to buy. But what about the rights of those that produce the food, which is eaten by those consumers? As Chavez says, “If that law passes, I’ll be the first to break it.” [It was later defeated in the California legislature. JG] Picketing, however, had been repeatedly blocked with injunctions, and as Gil and others concluded, until the green card was enforced and strike-breakers obstructed, organizing would prove the myth of Sisyphus. It seemed that the intensification of the boycott was the only hope to win. Of course, picketing of stores went hand and hand with the boycott. If enough of us could only get together we would win, was Gil’s point.

In my last week in Delano, the consensus seemed to be that the emphasis must immediately fall heavily on the boycott. As Larry Itliong said, if this year’s harvest could be blocked, and last year’s stored grapes kept rotting away, the contracts would have to begin to come, and the pitiful waste of grapes could end. But the boycott was such a hard thing. Who has ever tried to argue with a supermarket manager? It would take a lot more support to force dialogue. Another thing that irked Chavez was the lull in contact with the workers in the contract fields. He said it was not enough that they came to a meeting once a month to air their grievances. He did not want the union apparatus to become distant from the farmer. The workers in the fields, he said, must be constantly informed of developments in what is their own struggle. “We must stay together. In four or five years the grape-picking machines, which are ready now at the University of California will hit the fields. What will we do then if we are not together? It’s not the Schenley workers and the Delano strikers. It has to be all of us together, the United Farm Workers.”

At another California monthly meeting I attended, in Schenley, there was a great deal of grievance and concern for the future, even though the wage was now above two dollars an hour. As a vote was on the floor for a withholding of two dollars a month from each worker’s salary for their own union committee’s emergency fund, some workers were confused and thought the money was going to the Delano funds. Chavez walked to the front of the hall and said, “It’s not the two dollars we’re concerned about. We don’t want your money. We need your commitment, your strength!”

Naturally, the big planning meeting stretched into many continued meetings, for the figures and plans discussed were very complex. As I prepared to go back east, these meetings were still going on. Mac Lyons, a negotiator about to join the boycott and the creator of one of the “plans,” was still sitting through the long meetings, fidgeting on the edge of his chair. Someone said, “C’mon, Cesar, I want to get going.” And Cesar answered, “I know, we all do”, and then went on to insist that everyone must understand all the variables before they could vote and understand.

There are so many fronts, so many areas to cover and handle, so much resistance to such a basic cause. Yet after almost five years, I felt the strikers’ spirits had only strengthened. They are committed, and they will not give in. And if they are meeting resistance, they are also receiving much greater support than they once had. Donations keep pouring in. There are more and more requests for speakers from Delano to come and inform organizations of what is going on. As Pete Velasco told me my first night in Delano, “We stand together and try to achieve our goal through peaceful means. There is real love here. We don’t care what nationality or color a member or volunteer is if he is willing to work with us. If we can remain united and continue with this spirit, we will win.”

During one of the last meetings I attended, five Catholic Bishops appeared, several of whom have had long years of experience in labor management relations, to speak on their recent efforts to mediate in negotiations between the union and the growers. They had returned frustrated; the growers would not answer many of their questions and seemed as little willing as ever to negotiate. They would try once more, they said, this spring, and if things looked as bad, they would, on behalf of the National Council of US Bishops, urge every Catholic priest across the country to encourage their congregations to boycott grapes. But one striker spoke up and reported that he saw a new bumper sticker on a Delano vehicle: “Fight the Commies! Eat Grapes!”

Thinking back now, there were the long walks through the streets to my room each night, past long rows of monotonous one-floor bungalows. As I passed each house, a new angry little watchdog would set up a howl and bark and make his pretentious rush. It seemed each family had a bit of their security tied up in a set of fangs. Dolores Huerta, who never seems to rest, laughingly told me one night how Cesar had handled a group of skeptics at a meeting. “I never would have thought of it,” she said, “he just killed them with kindness. They kept pretending to be concerned, asking questions without caring to hear the answers. All the rest of us were getting furious. But Cesar just kept patiently giving these long, beautiful answers until they were so tired that they wished they’d never faked an interest.”

A grower’s wife also made an impression on me. She was working as a cashier at a supermarket in Delano, and was shocked that I should have come “all that way from out east to work with Cesar Baby and his kooks. He just wants money, just like us. He just likes the power,” she said.

There was also Jerry Cohen, one of the crack lawyers at the Forty Acres, intense and almost pulling his hair in frustration at Friday night meetings as he reported the employers demands, such as requiring Spanish-speaking workers to write out all their grievances in English or they wouldn’t be considered. Philip Veracruz, one of the union’s vice presidents, and once a Filipino migrant worker, was now in charge of the Filipino Retirement Village, funded by the union. Each time a new group of students came to visit, he would take an afternoon to talk to them, patiently explaining the history of strikes since the Great Depression. I remember him speaking to such a group once, with a controlled fury of conviction on the crime of surplus crop destruction: “While thousands right here in California are starving, what happens? Last year there was a surplus of oranges, what should have been a bounty and a thing of joy from God and the earth. But no, the prices may go too low if there are too many oranges, so they are dumped in huge piles, and kerosene is poured on them to keep off scavengers. Then they are burned! This is a crime against humanity.”

There was the joy of song at the Friday night meetings, the persistent smiles, and the steely determination, and Father Mark Day’s explaining to the Bishops that he was glad they were going to actively help the strike, for if the growers continued their refusal to negotiate much longer, even he would have to struggle to continue being nonviolent.

I picketed for one day in Oakland after leaving Delano. The indifference, even from minority groups, is frustrating. It becomes a two-minute verbal struggle with each customer heading for the front door of the market, and the struggle is often fruitless. We turned fifteen cars away in one afternoon, received countless pledges of “next time we won’t shop here,” and yet I couldn’t help but feeling exhausted, that as soon as we were gone there would be more droves of people coming in, many unaware of the issue. And there are so many stores and so few pickets. And the store managers always turn their vacant eyes at you: “We don’t order the grapes here. I have nothing to do with it. You’ll have to talk to the chain owner. No, his office is four states away. Well, sure, good luck.”

And yet the boycott has been gaining momentum. The chain stores may not be very upset when their small stocks of grapes do not sell, but they are moved when they see customers refuse to shop at all in their stores and take their patronage to stores that have the conscience to refuse to sell boycotted grapes.

I wonder about the future of the union. Should the strike be won, problems would still lie ahead not to follow the path of earlier corrupted unions, bureaucratically removed from the spirit and needs of the worker, rife with politics within. But the U.F.W.O.C. is determined to avoid that sort of pitfall by maintaining contact with workers, and winning in the only lasting way possible, through nonviolence and unity. From those I met at Delano, it is clear to me that there is great potential for other leaders in the union. And those that feel the union depends on the charisma of Cesar Chavez are mistaken. Cesar is loved, but his love will encourage others to lead after him. Too much has been accomplished to be undone.

As Mac, Steinbeck’s organizer from In Dubious Battle, explained to a comrade, “I guess we’re going to lose this strike. But we raised enough hell so maybe there won’t be a strike in the cotton. Now the papers say we’re just causing trouble. But we’re getting the men used to working together; getting bigger and bigger bunches working together all the time, see? It doesn’t make any difference if we lose. Here’s nearly a thousand men who’ve learned how to strike. When we get a whole slough of men working together, maybe—maybe Torgas Valley, most of it, won’t be owned by three men. Maybe a guy can get an apple for himself without going to jail for it, see? Maybe they won’t dump apples in the river to keep up the price.”

Of course it does matter whether or not the strike wins. And I for one believe it will. But even if it should lose, over the past five years, 18,000 farm-workers have gone on strike, and all of these workers know the power of unity. The important thing has happened. The different groups of farm workers have come together in a common cause, and the eventual breakthrough cannot be stopped. Delano is preparing to face another bitter harvest, and God knows we are with them.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article appeared in the March-April 1970 issue of The Catholic Worker; pp. 1, 7, 8. With thanks to Marquette University and The Catholic Worker for scans and permission.