Walking Satyagraha Reflections

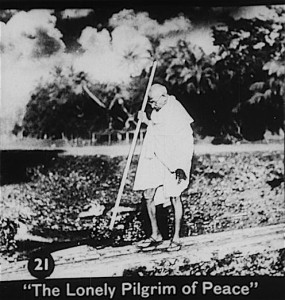

Gandhi on the Salt March, 1930; public domain photo; photographer unknown

The image of Gandhi in action, walking with a staff in his hand, is well known. We see it in newsreels, statues, films and photos. Thomas Merton described Gandhi as a human question mark. Perhaps we should amend that to “a walking human question mark” moving across the landscape. He was a man on the move, inquiring why injustices exist and how to remedy them.

When Gandhi returned to India after being away for years studying in England and practicing law in South Africa, he tirelessly traveled all over the subcontinent. He went to places where he was invited to resolve conflicts, and was constantly taking the pulse of the people of India, assessing their needs and views, diagnosing the nation’s ills, and, when possible, trying to address them with his legal expertise. During much of this period he traveled by trains in third class cars.

We can begin to comprehend Gandhi’s use of walking as a strategy by considering the Salt March of 1930. At first the strategy of civil disobedience in regard to making salt did not appeal to leaders like Nehru and Sardar Patel, but in time they realized that the issue of freedom regarding salt affected all—literate and illiterate, Hindu and Muslim—and that Gandhi’s plan of walking to the sea was dynamic. The action was pragmatic, because the poor peasants, living in such a hot climate where salt was an essential, were especially oppressed by the Salt Tax. And it was a deeply symbolic action, as the Boston Tea Party in America a century and a half before had been.

Gandhi organized the Salt Tax Satyagraha to include more than just making salt. It began with Gandhi and several companions journeying from the ashram where Gandhi lived near Ahmedhabad to Dandi, 240 miles away. This twenty-four day march gave the demonstration a chance for enthusiastic momentum to grow and the crowd of protestors to multiply, and for the cause to get sympathetic attention from people all over India and the world.

The march on foot arrived at the seashore at Dandi village in Gujarat, culminating with Gandhi defying British law by taking some crystalized salt into his hand, without paying a tax. At that time this tax was the second largest source of revenue for the British government in India, and it was a vivid symbol of colonial injustice, exploitative oppression. Many of Gandhi’s fellow protestors defiantly made salt there and the protest grew to a massive gesture of self-determination and self-liberation. The British responded by putting 100,000 rebellious but non-violent protestors in jails. This led to further steps toward self-rule for the people of India.

The significance of Gandhi’s use of protest marches has been underestimated. To underline their importance, the philosopher Ramchandra Gandhi asserted that: “Gandhi’s distinctive contribution to modernity as well as to tradition is a philosophy of walking which embodies the spiritual truth of nomadism, forgotten substantially by all civilizations, old and new.”

This is a profound insight, one the world has not fully reckoned with. To elaborate on this point, Ramchandra Gandhi contemplated further the implications of the “walking satyagraha” contribution:

“Not the going-a-begging of mendicancy, but the vibrant cinematic walking of satyagraha; very Chaplinesque, unanxious and yet fast-forward. Gandhi walks to Dandi and salt finds its savior, bland politics becomes salted with the truth of walking in truth, a very root meaning of brahmacharya. Gandhi walks up the steps of the Viceroy’s palace and extracts from Churchill the ‘half-naked fakir’ sneer—motorised, over-clothed, overfed, one-track, delinquent modern civilisation’s deep fear and hatred of the all-direction-ness of meandering, looking, loving, challenging, being. Monadism’s fear of nomadism. Gandhi walks to meet his murderer in the prayer ground, the walking lover stopping the bullets of hate, at least temporarily, not really the other way round. With Gandhi as model, Giacometti ought to have sculpted a ‘walking Man’ figure, dialectically completing his ‘standing Man’, ‘falling Man’ figures, symbolically and substantially pointing to a way out of stagnation and fall, i.e., the way of walking in truth, satyagraha. Gandhi is a line taken for a walk by God, in the manner of Klee’s great painting. ‘Speed is not the end of life,’ Gandhi said. ‘Man sees more and lives more truly by walking to his duty.’ Vanished nomadic wisdom would concur.” (Ramchandra Gandhi, I Am Thou: Meditations on the Truth of India, p. 203.)

In light of those lively reflections, I think it is useful to consider the symbolic importance of long marches, processions, walkathons and peregrinations of wanderers and pilgrims in history, and in Indian literature and elsewhere. Deep philosophies and value systems are often involved in such actions. There are deep roots in human activities done on foot. Dynamic engagement in symbolic motion is a dimension of physical behavior that is often useful in seeking justice, and it is a powerful aspect of satyagraha. To move confidently to a public confrontation in an act of civil disobedience is more dramatic than stagnant stasis and wishful waiting.

If we reflect on this historic image of active walking, roaming, hiking and wandering with added philosophical values we find it very rich with meanings. There are old traditions of people being in motion as a way of expressing freedom and detachment. The orders of Hindu sadhus (mendicants) include the rule to be ever on the move, not to stop in any one place too long, not to gather belongings, not to get attached. In fact, sadhus traditionally are not supposed to sleep in the same place two nights in a row. Like Buddhist monks, sadhus are dropouts who stay on the move; therein lies their freedom from worldly attachments.

I remember Professor Charles Long, as a guest speaker at Harvard Divinity School, discussing old human agrarian societies of semi-nomadic people, with cattle grazing over large stretches of land, and what happened when that way of life changed to a social structure of owning land. Prof. Long dramatically said that when people became sedentary, they went a bit insane. When people stopped moving on perpetually and pitching a tent temporarily, changing location with the seasons, circulating like other energies of the universe and organisms on earth, people lost something vital, he suggested. Owning land perpetuated a different ethos, he said.

The old stories of the great traditions have important images of wandering. Abraham wandered, called out from Ur to begin the new faith of Judaism. The wandering of Moses, going toward the Promised Land, was another archetypal scenario. The early Christian pilgrims of Ireland wandered wherever fate took them, surrendered to God’s will. Medieval pilgrims who went to the Holy Land are also part of western culture. In India, the great epics—Ramayana, and Mahabharata, are stories of exile, wandering in the forests, moving on while hoping for return. In ancient Greece the epic Odyssey, is another story of exile, adventures of wanderers en route to homecoming. Picaresque novels, like Don Quixote, and On The Road narrate adventures along the open road, revealing the traveler’s soul, and the characters of those he encounters. American folk hero Johnny Appleseed wandered in the frontier areas, planting orchards for settlers to use.

The 20th century philosopher Martin Heidegger explored the concept and experience of modernity being a period of homelessness and seeking experience of a homecoming. There are many displaced people, refugees and emigrants in our age. The discomfort of being unsettled, of searching for a new life, and the promise of arriving after a serious struggle are significant themes of many life stories.

American activist Martin Luther King, Jr., organized civil rights marches in the 1960s, which utilized public demonstrations. Protestors showed up, and joined together to walk to a symbolic place to show their presence to authorities, to make a demand, to seek justice. When police dogs, fire hoses, billy clubs, cattle prods or other implements were used to deter the marching protestors, the sight of oppressive power ruthlessly striking nonviolent victims gained sympathy for the protestors. (As the old saying about early Christianity goes, “The blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church.”)

In America during the 20th century a woman who called herself Peace Pilgrim walked across America repeatedly for the cause of peace for 24 years. She said, “A pilgrim is a wanderer with purpose.” And she explained, “In the middle ages pilgrims went out as the disciples were sent out—without money, without food, without adequate clothing—and I know that tradition. I have no money. I do not accept any money on my pilgrimage. I belong to no organization. I own only what I wear and carry… I am as free as a bird soaring in the sky… I walk until given shelter, fast until given food… My walking is… a prayer for peace.” She saw herself as “an embodiment of the heart of the world which is pleading for peace.” Her message was to “overcome evil with good, and falsehood with truth, and hatred with love.”

There are other pilgrims too, who have also tried to walk across America and other lands for peace or for some other cause. Stories in newspapers and on TV news sometimes feature these pilgrims. By walking through the land such people have drawn attention to important issues. Some have ended their journey sooner than they had planned, but that too, was a learning experience for them. They realized how much dedication it takes to undertake such an endeavor, for example. Dorothy Day, the American social activist said, “To me a pilgrim is someone who thinks ahead, who wonders what’s coming, and I mean spiritually. We are on a journey through the years—a pilgrim is—and we are trying to find out what our destination is.” Helping fellow pilgrims along the way was part of her philosophy of humility and service, foresight and mutuality.

I also find the reflections on walking and maturity in a book by David Jonas and Doris Kline intriguing. In an interview, poet Robert Bly paraphrased the ideas of this book, Manchild: Infantilization of Man, in this way: “…each generation of Westerners after the Industrial Revolution has been more infantile than the one before…An adult [is] someone who can exist in the physical world without a lot of supportive devices… in some mysterious way, such success matures a human being… If you walk from Boston to Labrador, you’re more mature when you arrive; if you drive, you’re more infantile when you arrive than when you left…”

Alfred North Whitehead wrote of the way living beings have adapted over the centuries:

“One main factor in the upward trend of animal life has been the power of wandering. Perhaps this is why the armor-plated monsters fared so badly. They could not wander. Animals wander into new conditions. They have to adapt themselves or die. Mankind has wandered from the trees to the plains, from the plains to the seacoast, from climate to climate, from continent to continent, and from habit of life to habit of life. When man ceases to wander he will cease to ascend in the scale of being. Physical wandering is still important, but greater still is the power of man’s spiritual adventures—adventures of thought, adventures of passionate feeling, adventures of aesthetic experience.” (Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World, New York: Free Press, Simon and Schuster, 1967, p. 207.) He also wrote: “Something new must be discovered. The human being wanders on.”

Einstein spoke of his own quest to fathom gravity in this way: “…years of anxious searching in the dark, with their intense longing, their alternations of confidence and exhaustion, and final emergence into the light.” Brian Greene, writing about this thought observed, “We are all, each in our own way, seekers of the truth and we each long for an answer to why we are here,” saying each generation climbs the mountain of explanation, always ascending a little higher, continually reaching for the stars.

Civilization, it has been said, depends on many individuals moving forward with their quests, their personal nomadic wisdom expressed in their life journeying and sharing what they have found with others. Each civilization needs these “questers” for its renewed stability and its long-term pilgrimage toward fulfillment. As Arnold Toynbee said, “Civilization is a movement—not a condition, a voyage—not a harbor.” Thinking, and living itself, involves a process in motion, it’s not a fixed and finished thing. In the long run, human beings always seem to find a way around impasses, refusing to stay stuck.

Satyagraha has been translated as “Truth-force,” “Soul-force”, “the appeal to conscience,” “voluntary sacrifice,” “pacifist activism,” “militant but nonviolent resistance,” and “the leverage of truth.” Satyagraha in Gandhi’s work usually included the physical presence of the protestor in an encounter. The opponent is approached and met eye to eye, protestors step forward and stand together, often linking arms in a phalanx, to paraphrase Erik Erikson (Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence) . It involves the solidarity of unarmed bodies standing present as witnesses protesting, not cooperating with injustice, but accepting suffering if it comes while resisting tyranny. This example has inspired many people around the world to attempt to find justice peacefully.

In recent years there are many diverse examples of protest marches around the world. In 2004, Indians in Columbia marched wearing traditional ponchos carrying ceremonial canes, walking 75 miles along the Pan American Highway to protest violence directed at their communities in the country’s long civil conflict; in 2010 Australian aborigines in the Outback marched in peaceful protests; in 2011-12 the “Arab Spring” demonstrations brought many changes, to name just a few.

South African protests for decades have used a unique kind of movement of the bodies of protestors, dancing in place, jogging without moving forward. It is called Toyi-toyi—jogging in place while chanting, and it presents a very energetic picture, with hundreds and thousands in motion—an ocean of energy, a dance of people seeking liberation, non-violent, non-clashing action. (See the video “How to Toyi-toyi”, which demonstrates and shows some protestors doing Toyi-toyi)

I find it wonderfully fitting that Gandhi was classed by Howard Gardner in his book about important people of the Twentieth Century, Creating Minds, with a dancer, Martha Graham, because both were judged by their public performances. They were “judged by others in terms of the effectiveness of their performances at a given moment.” Gandhi was a skillful person on the go, not an armchair philosopher. His last efforts of solving problems by way of a march were especially moving.

Gandhi, 1946 on his peace march; public domain photograph; photographer unknown.

Near the end of his life Gandhi walked across areas of northern India to stop the violence between Hindus and Muslims. Walking with a lengthy staff in his right hand and often with the support of a helper on his left arm, he walked barefoot through villages in Noakhali District of East Bengal for four months at the end of 1946 and beginning of 1947, at a time when riots had brought violence, murders, rapes and forced conversions, and the region was a tinderbox of fear and rage. The newsreel images of the thin and aged Gandhi patiently walking to quell the violence leave a vivid impression of Gandhi’s determination, sacrifice, hope and strenuous efforts. Gandhi walked to each Noakhali village and spent several days there, asking the people to take a pledge not to kill anyone. He responded to conditions like a skillful improviser. When adults were too fearful to come to a meeting in one village, Gandhi played ball with the children of the village for a half hour, then asked that the grown ups emulate their children and show some courage. In another place, while Gandhi was praying in an assembly, a Muslim man tried to choke him, and he responded by reciting verses from the Quran. The attacker released him, and, after apologizing, asked Gandhi what he should do. Gandhi asked him not to talk about the incident, for fear it might cause further riots. “Forget me and forget yourself.”

It may have been the dramatic impressions that this poignant Noakhali peace march made on Martin Luther King and others which helped inspire the American Civil Rights movement’s marches in Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and the March on Washington in 1963 Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote: “I was particularly moved by Gandhi’s Salt March to the sea and his numerous fasts. The whole concept of satyagraha was profoundly significant to me.” (The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr., p. 23) Viewing the documentary footage, one gets the sense that during the Noakhali march the frail Gandhi was putting his life on the line, that he could have expired from the exertions of walking, or could have died from the strategy of placing himself in the midst of the conflagration.

It is especially significant that Gandhi did not rely on words alone, but pro-actively put himself out there on the streets for the causes he believed in. He used his intelligence to learn how to accomplish his aims non-violently, and he taught others how to focus their energies and wander on and reach their goals. “The human being wanders on,” as Whitehead observed. And “Speed is not the end of life,” as Gandhi said, because “Man sees more and lives more truly by walking to his duty.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: William J. Jackson is a regular contributor to this site. He is professor emeritus of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University, and was the first Lake Scholar (2005-2008) at the Lake Family Institute on Faith and Giving, Philanthropic Studies Center, Indiana-Purdue University. His most recent publication is the novel Gypsy Escapades. New Dehli: Rupa & Co, 2012, on the themes of terrorism and satyagraha. We hope to review this book in the near future. Further information about Dr. Jackson can be found under the Editor’s Notes for his previous writings here, and is also available on Indiana University’s website.