by Vinay Lal

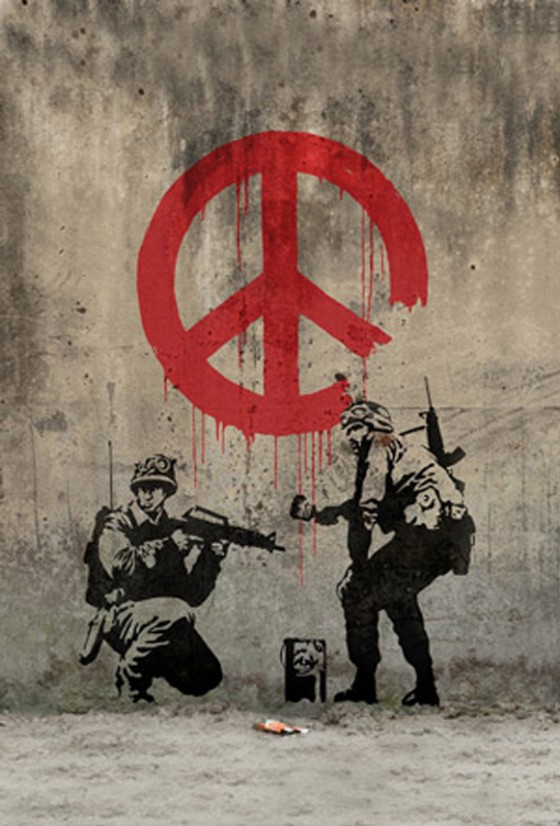

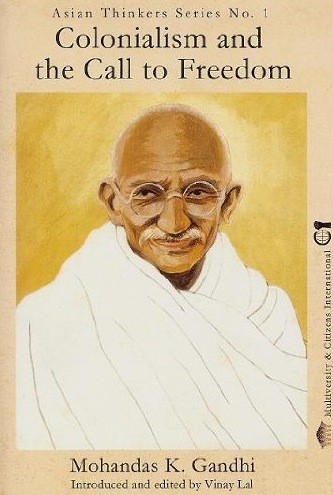

Cover art courtesy Vinay Lal

The enterprise of making a nation is fraught with violence. People have to be not merely cajoled but browbeaten into submission to become proper subjects of a proper nation-state. Overt violence may not always play the primary role in producing the homogenous subject, but social phenomena such as schooling cannot be viewed merely as innocuous enterprises designed to ‘educate’ subjects of the state. One of the most widely cited works to have put forward this argument with elegance and scholarly rigor is Eugen Weber’s Peasants into Frenchmen, where one learns, with much surprise, that even in the Third Republic, “French was a foreign language for half the citizens.” The making of France entailed not only the modernization of the rural countryside but creating, often with violence, proper subjects of a proper nation-state. The making of the United States offers another narrative of the role of violence in the production of the nation-state, with the extermination of Native Americans long before and much after the ‘Revolutionary War’ constituting the most vital link in the long chain of violence that marked the emergence of the United States.

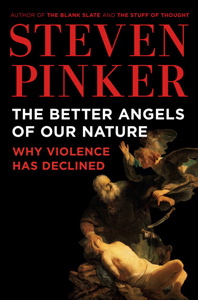

Postcolonial thought, attentive as always to the politics of nation-making and nationalism’s complicity with colonialism, bestowed considerable attention on the various phenomena that can be accumulated under the rubric of violence; however, it had almost no time to spare for a pragmatic, ethical, or even philosophical consideration of nonviolence. The violence of the nation-state may have always been present to the mind of postcolonial theorists, but generally this was reduced to the violence of the colonizer. One thinks, of course, of Fanon, Cesaire, Memmi, and many others in this respect. In those works that have underscored the complicity of nationalist and imperialist thought, a principal motif in the work (say) of Ranajit Guha, the violence of indigenous elites also came under critical scrutiny. (See, for example, Guha’s Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1999) It is characteristic of most social thought in the West that it has been riveted on violence – here, postcolonial thought barely diverged from orthodox social science, mainstream social thought, or the general drift of humanist thinking. Nonviolence is barely present in intellectual discussions. We see here history’s continuing enchantment with ‘events’; nonviolence creates little or no noise, it merely is, it only fills the space in the background.

Read the rest of this entry »