by Alan Drengson

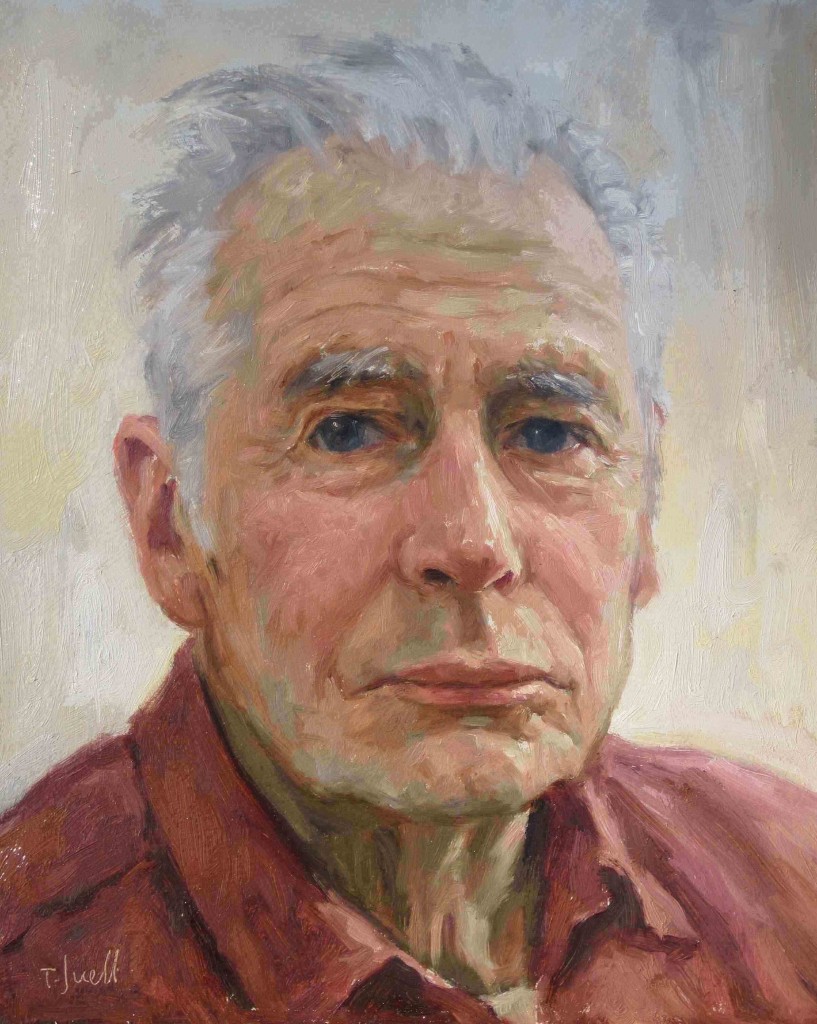

Tore Juell. “Portrait of Arne Naess;”

Tore Juell. “Portrait of Arne Naess;”

courtesy of the artist.

“Self-realization is not a maximal realization of the coercive powers of the ego. The self, in the kinds of philosophy I am alluding to, is something expansive, and the environmental crisis may turn out to be of immense value for the further expansion of human consciousness.” Arne Naess (In Drengson and Devall 2008, p. 132)

From his earliest major work, Naess used a deep and comprehensive approach for studying languages and communication. (The work is, Interpretation and Preciseness: A Contribution to the Theory of Communication, 1953. Now SWAN Vol I in The Selected Works of Arne Naess, 2005.) He united disciplines to explore languages as part of diverse communication systems in the natural and human world. These systems are open ended, adaptive, creative and dynamic. They are constantly adjusting to changing conditions in unique communities and places. Communication between and within species involves meaningful variations of qualities (e.g. in sound, light, odor, heat, color, pattern, and texture,) with a wide range of frequencies, intensities and velocities. We now explore the communication ecology of languages with broad analytical and empirical methods, some pioneered by Naess. By studying whole systems, we appreciate the creative, place-based, knowledge skills of cultures woven into the other systems of the natural world. Diversity, complexity and creativity are important for environmental integrity, cultural richness, and personal freedom. Naess noted that when we know the ecological context, it helps us to understand one another without translation, even when from different cultures with unfamiliar languages. Knowing communication ecology helps us to resolve conflicts nonviolently. By having a sense for these whole systems, we are aware of the challenges to precise interpretation; this engenders positive cross-cultural and interspecies communication exchanges.

Naess loved diversity and appreciated the role of dialects in evolving systems of language families. He learned from empirical studies and by knowing many formal and vernacular languages (living and dead), that it is difficult to give precise (universal) definitions. There are many ways to feel, see, say and write things. He used a descriptive approach to study linguistic communication. He remarked in The SWAN (see the Appendix below for excerpts) that his view contrasted with analytic philosophers in England and elsewhere, who used a prescriptive approach, suggesting there is one right meaning and that a single language reflects reality more precisely than others. Their views were more insular; they did not study dialects and the cross-cultural, natural context of language families (such as Indo-European) that we study in communication ecology. Communication ecology enabled Naess to reach a mature, whole understanding of human life in the evolving, changing Earth. The culture that he grew up in accepted multiple dialects, perhaps because there was no Norse king as authority for proper Norsk. For several centuries the rulers were not Norwegians but foreigners. In the English speaking world there was the authority of the “King’s English.”

Read the rest of this entry »

“Silent No More”. Poster art by

“Silent No More”. Poster art by