by Lawrence Rosenwald

For most of my life, reading literature has given me some of my most intense and purest experiences. I know from these experiences what Nabokov means when he writes, “ . . . a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm” (316-7); what Kafka means when he writes, “a book must be the axe for the frozen seas within us”; what Emily Dickinson means when she writes, “if I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry” (NA I: 2483). A society that sought to deprive readers of such experiences, that sought to keep writers from creating works in relation to which such experiences might be found, would seem to me cold and impoverished – the frozen seas would remain within us, with no axe to break them up.

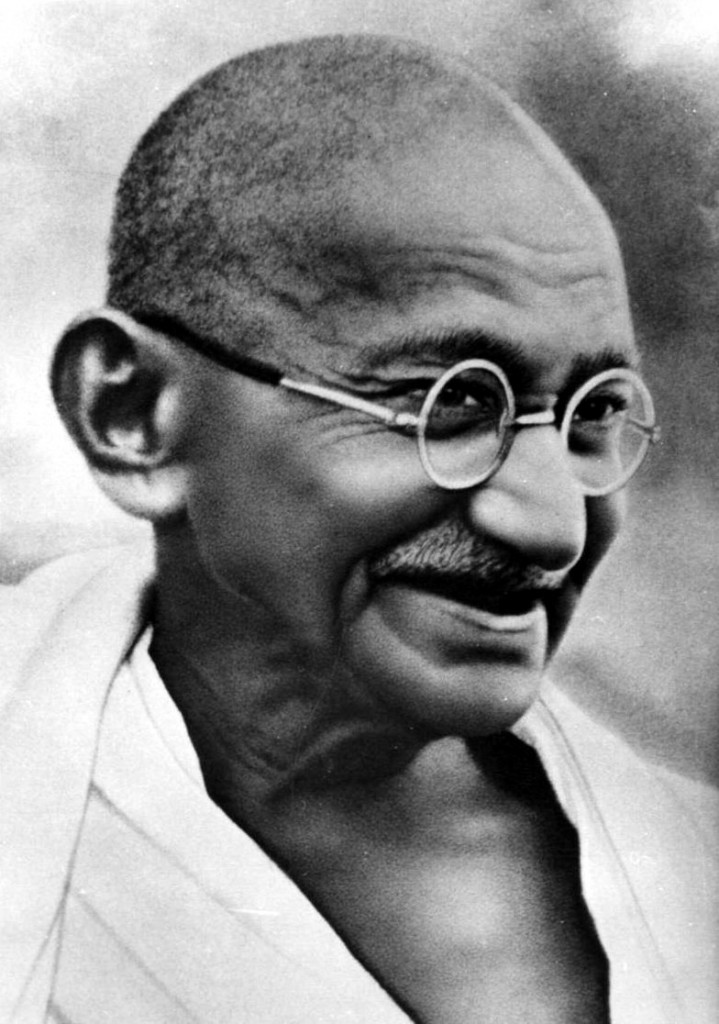

More recently, I have also become intensely committed to nonviolence – to nonviolence in relation to national conflict, i.e., to pacifism, but also to nonviolence as a way of life.[1] I am a modestly obedient citizen in most spheres of public life; in this one, I have become a deliberate and assertive lawbreaker. For the past sixteen years, when my wife, Cynthia Schwan, and I have paid our federal income tax, we have subtracted from what we owe (though I don’t believe that “owe” is the right word for our relation to the government in this matter) the percentage of the federal budget that goes towards current military expenses, sent the subtracted percentage to progressive organizations or a progressive escrow fund, and informed the IRS of the action that we have taken. This is, as noted, illegal, and the IRS has accordingly seized the money we have refused to pay, either from our bank accounts or from my salary at the college. I do this annual act of civil disobedience because, just as I refuse to endorse a world without literature as I might imagine it, so I refuse, with equal intensity, to endorse the violent world I actually inhabit, the world of East Timor and Rwanda and Bosnia and the sanctions on Iraq, and in particular the violent country I inhabit, with its military budget that is by far the largest in the world, greater than the military budget of the twelve next largest military budgets combined.

Read the rest of this entry »