by Terry Messman

“Martin was attuned to the Hebrew prophets, and that was their constant message: Don’t talk about loving God or being religious unless you stand with the outcasts and the weak. Jesus said the same thing. There’s no way to understand Martin’s urgency about standing with the poor without taking into consideration his deepest religious grounding.” Vincent Harding

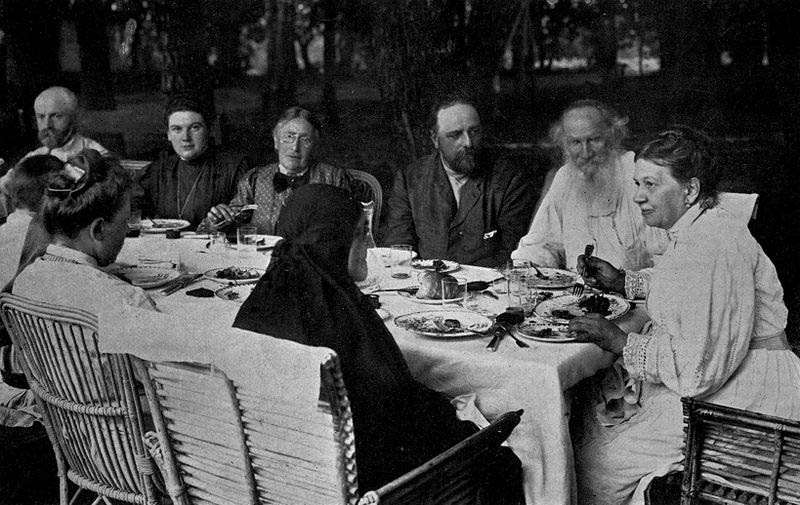

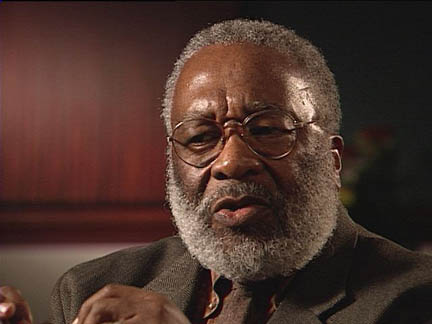

Vincent Harding, c. 2013; photographer unknown.

Street Spirit: In your book, Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero, you wrote that the public seems most aware of the first part of Dr. King’s journey that culminated in his “I have a dream” speech during the March on Washington in August 1963. Yet, in the final year of his life, King attempted to build a far more militant movement that could challenge racism, the war in Vietnam, poverty, unemployment and slum housing. What are your reflections on Martin Luther King in the last year of his life?

Vincent Harding: Well, Terry, I think that he was, as much as anything else, a man in search. He was not simply repeating himself, but trying to develop himself. It was clear that he was responding to the world that he was living in, and the world that was coming into being all around him. I think that that element of being engaged with the world as it was developing is one of the most important things that I would see.

He was trying to speak to the developing Black consciousness that was rising up in the Black community. He was trying to speak to the younger people who probably, even more than they knew it, were responding themselves to the society’s tendency to see them simply as waste material. He was trying to understand ways in which he could help those young people to see a sense of purpose for their lives, beyond the explosive kinds of actions that they were engaged in, in the urban areas of this country.

And then, of course, he was trying to respond to his country’s imperialism and militarism. And that was something that he simply could not let pass him by. It was absolutely necessary to speak to what that militarism was doing to the country — especially as expressed in Vietnam.

Because he was a deep lover of his country, he felt that there would be no way in which he could be a person of integrity, and be silent about the damage that he saw us, as a nation, inflicting on ourselves and on other people. And, of course, in the midst of this period, he also tried to figure out how the wealthiest country in the world could respond to the growing damage that it was doing to its poor people. That whole question of poverty, and the response to poverty and the response to the poor, is another element, I would say, of his overwhelming concern.

I’d like to mention one other thing, though. And that is that if we’re talking about that last year, he is really constantly trying to understand what would nonviolent revolution be like in America. And, at least as important, how would he call the angry, explosive, young people into that kind of task — for the good of the country, for the good of themselves, for the good of the world.

This whole matter of the young people — their explosive energy somehow being called into participation in a nonviolent revolutionary change and struggle — that was something that was very much on his mind and heart, and that needs to be seen as crucial to those last years.

Read the rest of this entry »