The Nonviolent Shift

by Ken Butigan

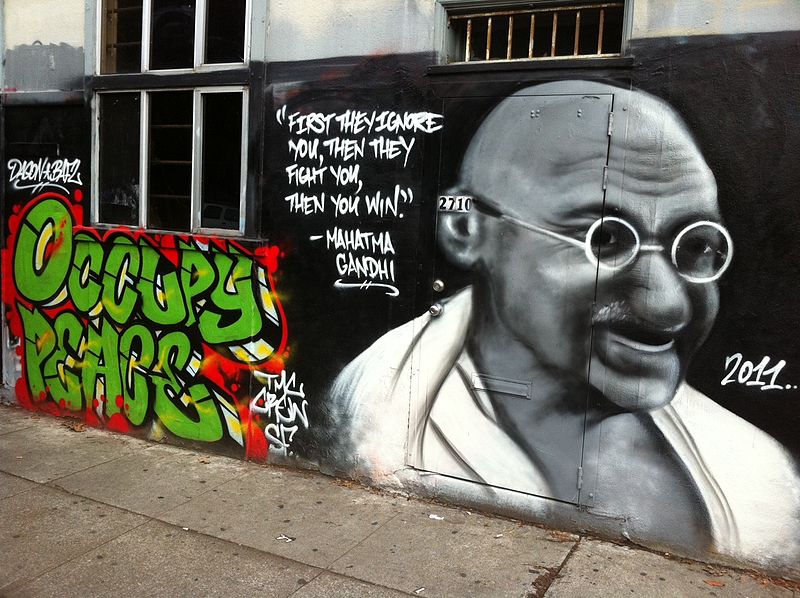

“Then you Win”; Occupy graffiti;

Artist unknown; posted on

wagingnonviolence.org

For some time I have been increasingly convinced that, in spite of the horrific systems of violence and injustice that grind away, we are in the midst of a long-term “nonviolent shift.” By this I don’t mean we will create a utopia where conflict, violence, and injustice cease to exist. Interpersonal and structural violence — reinforced by a deeply rooted violence belief system — are grim realities that humanity will long have to face. The nonviolent shift, rather than portending an ideal society, here signifies a world where people are increasingly equipped with the tools to challenge, transform, and heal violence and injustice in a more powerful, creative, and effective way.

The Egyptian revolution, which began just over a year ago, was dedicated to ending a thirty-year dictatorship and sparking a long-term process of transformation within the country. But like many other powerful movements, it has also had unintended world-historical consequence that have helped to boost the momentum of this shift.

It has done this by casting light on both the future and the past.

The revolution in Egypt lit up avenues for hope and action going forward that had only been dimly seen or imagined before then. Together with the founding events of Tunisia weeks earlier, the spark that became the Arab Spring unleashed the still-unfolding impact in the Middle East and around the world, including the Occupy movement.

At the same time, it also shed light on the past in a new way. The power of ordinary people to shake the pillars of a deeply entrenched dictatorship in Egypt has prompted us to carefully reassess the role, power, and historical place of past nonviolent movements. Not only does its success impel us to more clearly comprehend and honor individual past people-power initiatives (for example, pro-democracy movements in The Philippines, Chile, Argentina, Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, South Africa, Indonesia, East Timor, Serbia, Georgia, Ukraine, and Liberia, as well as many much less visible struggles), it forces us to reframe our understanding of the phenomenon itself.

Nonviolent change, increasingly, is not an exceptional or isolated case. It is not a “lucky accident.” It can be understood, in an increasingly definitive way, as a powerful and even methodical alternative to either violence or passivity. And Egypt is one of the watershed events that has moved this, for many, from a hunch to a increasingly viable course of action, chipping away at a deeply-entrenched worldview that previously “couldn’t see” or “couldn’t compute” the facts right before their eyes.

Egypt sends us scurrying back to our history with new eyes. Just as the liberative gumption of the modern women’s movement in the 1970s prompted a new wave of scholars to scour history to discover and reclaim the agency of powerful women through the centuries, so the events of the Arab Awakening stimulate us to retrieve and understand in a new way the often hidden history of nonviolent change. It can help us to see this history not as a series of isolated and misremembered events but a forceful tradition that, over the past century, has gained accelerating momentum and significance.

In his classic study The Structures of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn proposed the notion of a paradigm shift, in which the prevailing model of science gives way to a more adequate model as anomalies (exceptions to the status quo) accumulate. The classic example was the shift from Newtonian to Eisteinian physics, but there are many other paradigm shifts in science and other disciplines. The nonviolent shift — from a governing worldview where violence is the default to one that increasingly recognizes that we have the power to create and apply alternatives to violence — is a long-term process. But anomalies are accumulating. In addition to the contemporary plethora of nonviolent social movements and campaigns, there has been a proliferation of tools for nonviolent transformation (restorative justice, nonviolent communication, trauma healing, anti-oppression training), a dramatic increase in the study of nonviolent change (empathy, forgiveness, creativity, movement-building), and an increasingly emerging worldview that stresses the interconnectedness of the planet and its inhabitants.

And every once in a while an anomaly rolls by that just seems too good to be true, like the recent call for applications by the University of Massachusetts Amherst for a new faculty position called the Endowed Chair in the Study of Nonviolent Direct Action and Civil Resistance.

When I first went to work in 1990 for Pace e Bene, a small nonviolence training organization, we were often confronted with befuddlement if not incomprehension at the word nonviolence, let alone the practice to which it referred. In the activist circles that we traveled in, “nonviolent direct action” and “civil resistance” were standard accessories, but in academia (where I taught occasionally), one was often met with a polite distance that communicated an incapacity to see how this could relate to “real” academic subjects.

Something is happening.

A year after the Egyptians brought down Hosni Mubarak, their revolution continues to unfold, encountering all the obstacles and reversals that most successful social movements face in their attempt to create enduring change. The nonviolent shift is not easy, and will face harsh reprisals from a system that’s been in the driver’s seat for thirty years (or 5,000, depending on your short or long view of things).

Once in a while, though, there are signals from a nonviolent future: the roar of two hundred thousand people jamming a city square — or, at the other end of the cosmic telescope, an out-of-the-blue job announcement.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Ken Butigan is director of Pace e Bene, a nonprofit organization fostering nonviolent change through education, community and action. He also teaches peace studies at DePaul University and Loyola University in Chicago. We wish to thank both Ken Butigan and Waging Nonviolence for permission to repost this article.