Singing of Liberation: The Street Spirit Interview with Country Joe McDonald, Part Four

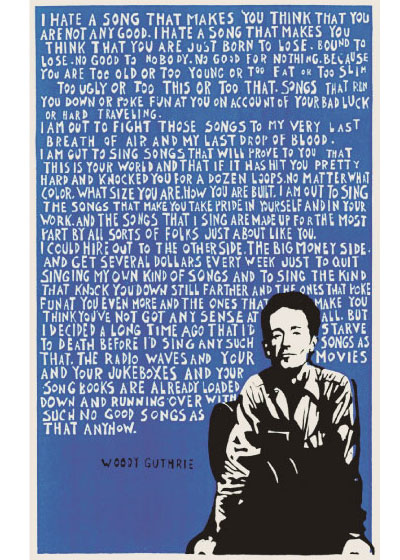

Woody Guthrie poster courtesy countryjoe.com

“I knew a lot of the people had to escape or they were killed by the junta in Chile. It was just tragic and terrible. I had grown up with a full knowledge of the viciousness of imperialism from my socialist parents. So I knew that, but I was still shocked.” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: Robert W. Service called his poems about war “songs from the slaughter mill.” How did it happen that an acid-rock musician of the Vietnam era transformed poems written about World War I into a powerful musical statement in your album War War War?

Country Joe McDonald: When I got out of the Navy and was going to Los Angeles State College, I got a job working in East L.A. at a breaded fish factory. When I was coming home from work, I stopped at a used bookstore, and I saw a book called Rhymes of a Red Cross Man. I took it home and read the poems by Robert W. Service. His brother was killed in World War I and he himself was a Red Cross man during the war — a stretcher-bearer and ambulance driver. I knew about his frivolous, entertaining poems set in the Yukon, like “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” But I was really struck by his poems about war; they’re very different. I just thought they were great.

Spirit: Why were his poems so meaningful to you?

McDonald: They were poignant or humorous poems that were approaching war from different points of view. I just liked them and I thought they were really good. And I liked the little watercolor paintings that illustrated it. One particular poem, “The Ballad of Jean Desprez,” really affected me.

Spirit: You gave a very emotional performance of “Jean Desprez” on your album. Why were you particularly drawn to that poem?

McDonald: It’s a story of a peasant boy who tries to save a wounded French soldier from the German soldiers. He’s given a choice in the end of this very long ballad. In the end, this little boy turns on his oppressor and shoots. It’s a surprise ending. I put it together with music when I first moved to Berkeley in the mid-1960s, and I knew it was great, because it’s a ballad about eight minutes long, but when I got to the end, I started crying because it was so dramatic. And the melody I found was such a great vehicle for it.

It took about five or six years before I could even perform it without crying. So I knew it was really great, and I would sing it at hootenannies and stuff. Before Country Joe and the Fish, I was just a folksinger guy hanging around in Berkeley at hootenannies and I would sing it. It was part of my repertoire and it was really appreciated and people loved it.

So time went on, and we formed a rock band and Country Joe and the Fish got signed on to a recording contract. Then after I did my first solo album, I got the idea of making a whole album of these poems of Robert Service. So I did. I looked through Rhymes of a Red Cross Man, and picked out the poems that I thought were really great and I found vehicles musically for those poems.

It just fell together and I recorded it by myself for Vanguard and they released it. War War War has been a regular seller for 40 years. But they stopped making it in LP form so it occurred to me that I should make it into a CD, so I re-recorded it live in Vancouver. I think it’s one of the best musical statements about war that has ever been made. I still think it’s phenomenal.

“Every Corpse Is a Patriot”

Spirit: “The Munition Maker” is about a man who sits “on a throne of gold” earned from selling the weapons of war. He realizes too late that he shouldn’t have wasted his life worshipping money and military arms and warns the world to turn away from war and work instead for “pity, love and peace.” To me, this song seems more powerful than Dylan’s “Masters of War.”

McDonald: Yes, that song is powerful and it became poignant musically with the organ’s drone through it and the 12-string guitar. And I really love the poetry of it: “Be not by mammon cowed.” You can’t help but think about the Krupp family in Nazi Germany and Dow Chemical. It’s a very romantic song and it is very moving.

Spirit: What other songs from War War War did you feel were especially powerful statements about war and peace?

McDonald: On the album, the song that does it to me is “The March of the Dead.” It’s unbelievable. The troops are returning from the Boer War and everybody’s cheering because they’re home and they hold a ticker-tape parade. But then amongst the crowd, some people are not too happy; they’re thinking about the people who have been killed. And then they see an image of the dead marching along with the living that have returned from war. And they’re all wounded and they’re all fucked-up and they’re horrible to look at, and it’s just so shocking that the dead are marching.

And musically, it’s very moving. I just stumbled onto some dream-like melodies. It concludes with the warning that all of you people who are really happy that the war is over and finally you can get back to your regular life, never forget the dead. Don’t forget the dead!

The folksinger from New York City, Dave Van Ronk, wrote a song called “Luang Prabang.” He has a line in the song about the war dead: “All over the world, there are spots where the corpses of your brothers rot. And every corpse is a patriot. And every corpse is a hero.” And that’s where I’m at! That’s where I’m at! Some of those corpses you may not really feel empathy for, but to somebody, they’re heroes and patriots.

Spirit: It reminds me of Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front, and how it shows the humanity of young soldiers trapped in the German army. We may hate German militarism, but it feels like the end of the world when just one of the young soldiers dies.

McDonald: Oh yeah! Victims! We’re all victims of war!

Two Tributes to Woody Guthrie

Spirit: You did one of the first and best tributes to Woody Guthrie. Why did you record Thinking of Woody Guthrie?

McDonald: I grew up with Woody Guthrie’s music because my parents had his songs on 78 rpm records and I listened to him. When I got a contract to record with Vanguard Records as a solo artist, I did the War War War album. The producers at Vanguard wanted me to go to Nashville and record a country album with session musicians at Bradley’s Barn (a recording studio in Nashville). So I did that. We booked three days and went down there. When I grew up as a kid, I had listened to a lot of country music, and I picked out some really good favorites of mine.

Spirit: Your country album, Tonight I’m Singing Just for You, came out in the early stages of what would later become a whole country-rock movement. But it was pretty unexpected in 1969 because here’s this San Francisco acid-rock guy who is now recording country songs with a great set of Nashville players.

McDonald: Well, I grew up in El Monte, California. A lot of displaced Okies lived in that part of Southern California. My father was a displaced Okie, and he liked country-western music. There was a thing like the Grand Ole Opry West Coast that was near us, and it was called the Hometown Jamboree. All the country-western people played there, and it was on television and the radio.

I listened to a lot of country-western music when I was growing up. So I knew all of those country songs, and we did the recording really fast because these session musicians were really great. We knew we’d have a day and a half left over and the idea was thrown out that we should do a Woody Guthrie album. So we recorded Woody Guthrie with the same musicians.

I don’t think they’d ever heard of Woody Guthrie before. They didn’t even know who Woody Guthrie was. But Marjorie Guthrie (the wife of Woody Guthrie) loved that album because I don’t think that Woody Guthrie had ever gotten a serious treatment from truly excellent country musicians before. That was the thing about that album. These musicians were the top of the line. And, as a matter of fact, they were also the top of the line conservative — really conservative; pro-war, Republican conservative.

Spirit: It’s pretty funny to think of Guthrie’s radical populist songs like “Pretty Boy Floyd” and “Tom Joad” performed by conservative Nashville musicians.

McDonald: It was full of contradictions, you know. Full of contradictions — and it turned out great. And the Woody Guthrie album is still available today.

Spirit: It’s still my favorite collection of Woody Guthrie’s songs ever recorded. It was one of the very first Woody Guthrie tribute albums, wasn’t it? It was released only a couple years after his death.

McDonald: Maybe it was the first — the first tribute to Woody Guthrie.

Spirit: Several years later, you created “A Tribute to Woody Guthrie,” a one-man song and spoken-word performance. How did that come about?

McDonald: Marjorie Guthrie knew I had recorded the Thinking of Woody Guthrie album, and as a result, I was included in the Tribute to Woody Guthrie at the Hollywood Bowl in 1970. The Woody Guthrie thing just kept going. I had these letters that Malvina Reynolds had written to Woody Guthrie about a box of cookies and Woody’s response when he was in the hospital about Malvina’s cookies. And I had some things that my Dad had written about Woody and songs that he liked, and songs from my album, and I thought that I’d put all these words and things together and make a tribute to Woody Guthrie made up of my songs and some of my favorite writings of Woody Guthrie, some of which other people didn’t know about.

They didn’t know about the cookie letters and they didn’t know about his “Woody Sez” columns, pretty esoteric stuff. A lot of people don’t know the things that he did. So I put it all together, and I performed it for 11 years. I couldn’t believe it! I started in Berkeley and I did it for 11 years all over the country. I did it in England a couple times, and I did it at the 100th anniversary of his death. I recorded an album of it. It was quite successful.

Spirit: What does Woody Guthrie’s music mean to you? How do you see his place in American song?

McDonald: That’s difficult to answer because I grew up with Woody Guthrie’s music on 78 records. He was really a good topical songwriter but I’m amazed that he became such an icon. He was also an Oklahoman like my father, and my father had a bit of Woody Guthrie in him, for sure. He was a Dust Bowl refugee, so I kind of latched myself onto the Woody Guthrie phenomenon. It just was natural for me to do. I felt he was like a cousin of mine.

Singing at a Street Protest

Spirit: Longtime Berkeley activist Dan McMullan told me how happy he was when you performed at Arnieville, the homeless encampment that was organized to protest cuts to low-income seniors and disabled people. How did you get involved in performing at this protest?

McDonald: Well, it was a good cause. I knew Dan McMullan and if a certain situation attracts me, I come out and do it. I like to keep doing things and performing in odd situations, so I liked the idea of that performance. I don’t do a lot of homeless concerts. Homelessness freaks me out. I feel guilty that I have a home, and I don’t know what to do about it.

Spirit: It’s a great image of you singing at a homeless encampment from a little stage they made out of a wooden palette on a street corner.

McDonald: It was just a sign of the times that we were doing that concert in the meridian for the little encampment out there, and I was singing on this strange little stage that was set up. I don’t even know how they got the P.A. system there.

We were in this meridian on the streets of Berkeley and the strange thing about that particular performance was that just half a block away, someone had been gunned down and killed. That was all the talk in the camp, about this guy who had just randomly been killed. And that was right next to a home that was low-income housing for elders right there. And also, the Berkeley Bowl food market is right across the street.

So you had the juxtaposition of these things all happening at this one time in this one place. I never could have predicted that they would be talking about a killing, and we were all thinking, “Wow, are we going to get shot?”

I thought, I’m here, I’m protesting this, I’m just entertaining the people that were there, that’s all I was doing. And then I was thinking that there’s the Berkeley Bowl right across the street with all this food that these people can’t really afford, and there’s a guy who just got shot half a block away, and will we get shot, and then there’s this low-income housing. I was just trying to put it all together — and it was psychedelic, huh?

Spirit: When we did housing takeovers in rough parts of East Oakland, we ran into the same kind of stuff. What’s striking is that you began singing on the streets of Berkeley in 1965, and here you are decades later, still singing on the streets for a worthy cause.

McDonald: Well, it’s just another platform for music. I’m a musician and I sing all kinds of different things. Like I said, if it feels good, and it’s the right thing for me, and it attracts me in some way — it was great, so why not do it?

Spirit: Many veterans have been wounded, traumatized or disabled in war, and many suffer economic hardships or end up on the streets. What do you think about veterans ending up homeless?

McDonald: Well, it’s just all about economic priorities. The priority is economic prosperity and investing in war. There isn’t any budget for taking care of homeless people.

It was interesting, because at the Veterans Day ceremony in Berkeley last year that you were just talking about, Councilmember Kriss Worthington gave a little talk about the importance of us taking care of our veterans because so many veterans are homeless on the streets, and we’ve got to do something about it. Then Mayor Tom Bates got up and said that the federal government needs to step up and do something about this problem. I really agree because it’s of such a magnitude that there is no local budget to handle it. The pie has been sliced up too many different ways.

Veterans make up a certain part of the homeless population. A shocking number of veterans are homeless. But we have an enormous homeless population everywhere you go. Everywhere. Every time I go into San Francisco, I can’t believe it. Even in Berkeley they’re just camped out all over the place, and no one seems to be able to do anything about it.

We have billionaires. We’re spending billions and billions of dollars, but the government and those people who have big money and control are not giving any money towards solving this homeless problem. You know, I can go down the street and give a few bucks to a homeless person so they can buy a little something to eat, but I can’t personally solve the problem. And the city of Berkeley can’t solve the problem, and actually, the city of New York can’t solve the problem.

It’s going to have to come on a national, governmental level. It has to be the federal government. It can’t be just a benefit or a benefit concert. All those things help, and we do what we can, but the homeless problem is enormous.

It’s causing, in my opinion, a psychosis. People are becoming homeless and the insecurity of not being able to make your dreams come true creates complicated problems. It’s very complicated and it needs to be solved by inspirational leadership and money coming from the national level. It actually needs to be addressed on a global level because homelessness is not only in America. We have an overpopulated planet which is struggling to feed seven billion people now.

Songs of Liberation

Spirit: I went to a great Brian Wilson concert in San Francisco and they did “California Saga” from the Beach Boys’ Holland album. I was so surprised when Al Jardine sang these lyrics about you.

Have you ever been to a festival — the Big Sur congregation;

Where Country Joe will do his show, and he’d sing about liberation.

Did you realize they sang that song about you?

McDonald: You know, the song does ring a bell. I’m very surprised Brian Wilson is still playing it in concert.

Spirit: I wanted to figure out why exactly Al Jardine wrote those lyrics about your songs of “liberation” for the Big Sur “congregation” and I discovered that the Beach Boys, Country Joe McDonald and Joan Baez all performed at the Big Sur Folk Festival on October 3, 1970. That’s where those Beach Boys lyrics originated. You performed “Air Algiers” at the festival. Do you remember the Big Sur Folk Festival?

McDonald: I do! Although it was actually held in Monterey. “Air Algiers” was part of my repertoire at the time. That was not a happy period of my life. I was trying to adjust to the band disappearing and other personal issues. I think I’m probably the only singer-songwriter that wrote about the flight of Black Panthers leaving the country to go to Algiers. The song’s about Eldridge Cleaver. I was taking on the persona of Eldridge Cleaver when I sang, “I can remember seeing my picture on the post office wall. I can remember the day that the FBI called.”

Spirit: You were now a solo act because Country Joe and the Fish had disbanded. The band was creating important music and was a popular concert draw, so why did the band members break up?

McDonald: Well, the manager started firing people, I guess. People would have a conversation with our manager and then they’d leave. I don’t know. They didn’t get along. It’s too bad the original members didn’t stay together, because we had something going. The Grateful Dead managed to stay together. But we didn’t stay together, and the band began to fall apart.

We were overworked, but the most important thing was that many of the original players left — Bruce Barthol left, David Cohen left, and Chicken Hirsh left. I remember talking to Chicken decades after he left the Fish. He said that a few weeks before Woodstock, he came into the office and he thought, “I’m going to quit today.” And he quit! It’s just weird. By the time we played Woodstock, it was not the original band any longer. For the first year or so, I had the power to force the band to rehearse, and play those complicated arrangements. But after a while, it was impossible.

Spirit: Why did it become impossible? And why did people just walk away when the band was still at a peak?

McDonald: It just fell apart. They just wouldn’t rehearse and wouldn’t play the complicated arrangements any longer. They began to just play the simpler stuff. It’s really hard to play “Section 43” and “Grace” and “The Masked Marauder.” Those are very complicated pieces of music and without rehearsal, they can’t be played. And we had new people coming in, and we just started playing the simpler stuff.

Also, we never had a sympathetic record company. The record company never said, “What can we do to help you be The Fish?” They just said, “Time for a new record, time for a new record, time for a new record.” And the management was saying, “Time to go to work, time to go over here, time to go over there.”

I remember at one point we went to Hawaii and then New York and then England and then back to California in like four days, and we were going, “What the fuck is going on here?” I don’t know, maybe it was doomed from the start. But you know groups go through periods where they’re not so good, or they’re better than they were, and then they have changes in personnel. It all just fell apart. And I remember getting sick of it, and I didn’t like it. I hated it. And then the miracle for me happened at Woodstock when I got a solo career.

Spirit: You actually ended up hating the band at that time?

McDonald: The vibes were wrong. We were not having fun. We went from having a lot of fun and loving playing music with each other, to hating playing with each other and not having fun.

Spirit: You wrote virtually all the songs on the first two widely praised albums, didn’t you?

McDonald: Yes.

Spirit: Barry Melton was a crucial part of the Fish, and he never came back, right? Did you guys have a falling out?

McDonald: Oh, we had a big falling out — to this day. We didn’t get along. He just wouldn’t cooperate, and it just all fell apart.

Allende and the Coup in Chile

Spirit: I was fascinated to learn that you were in Chile writing music for a political film at the time when Salvador Allende ran for the presidency.

McDonald: Well, it was a fanciful melodrama, taking place at the time of the Allende election, called Que Hacer and made by the leftist filmmakers Saul Landau, Raoul Ruiz and Nina Serrano. I wrote most of the music for the film.

Spirit: The film had footage of Allende’s election. What did you feel when the CIA and ITT staged a coup in Chile and Allende was assassinated after the film was completed?

McDonald: It was horrible because I met people who were Miristas — from the MIR — during the time we were in Chile. [Editor: The MIR or Movimiento de la Izquierda Revolucionaria, was the Revolutionary Left Movement in Chile. TM] I knew a lot of the people and we knew they had to escape or they would be killed by the junta in Chile, literally. People that we knew were killed. It was just tragic and terrible. But also, I had grown up with a full knowledge of the viciousness of imperialism from my socialist parents. So I knew that, but I was still shocked.

The MIR was a revolutionary group that was behind the election of Salvador Allende. They were seizing land, and they were in every aspect of Chilean life, in the upper and middle class, in the working class and in the military. They were everywhere. When I asked somebody where the Miristas were, they said, “Well, we’re everywhere.” Because they had to be secret; they were anonymous.

But when Pinochet took over, they ferreted out the Miristas, and when they found you, they either imprisoned you or killed you, or you escaped. A lot of them escaped up to Canada and got the hell out of Chile. When I left Chile at the Santiago airport, there was an image of Che Guevara on the TV screen when I went through the checkout line. But then everything was different.

Spirit: It became a different country because Pinochet and the Chilean military tortured and killed thousands of people.

McDonald: Everything was different because there was a dream of a socialist utopia for Chile and then it all ended. It turned into a nightmare. It just happened so quickly. It’s horrible. It’s a constant struggle with human beings. I don’t know why the hell we’re on this planet, but we’re stuck here together, and we can’t seem to get along.

Sources of Inspiration

Spirit: What people have been sources of inspiration in your life?

McDonald: Pete Seeger inspired me in the way that he involved the audience in his performances. He inspired me as a person, and in many ways. But I saw him also as a father figure. Florence Nightingale inspired me. When I was younger, I was inspired by Black musicians, and by the spirit of the blues and also rhythm and blues. The blues just spoke to me and provided me a solace to this day that I find in nothing else.

Spirit: Why do you find solace in the blues?

McDonald: I don’t know. You know, there are certain universal feelings. There is a commonality from what you hear from a mosque and Mississippi Delta Blues, and also the Child Ballads [Editor: The traditional ballads compiled by Francis James Child in the 19th century. TM] There is a commonality. And there is a theory that there was an original sound and an original kind of music that touches us in a way that no other musical sound touches us. And I find that very true, personally, for me. I find a protective, safe place in the sound of this ancient merger of Eastern and Western music that probably went back to original African sounds.

Spirit: Many say that blues and gospel music created in the African American community are the most original and influential musical art forms in our land.

McDonald: It is very rich. I’m also fascinated by Sacred Harp singing and shape note singing. When I hear that shape note singing, I just love certain musical sounds. I’m just in love with them and I cannot imagine life without them.

Spirit: Is this music more important to you than the rock music from your era?

McDonald: I like the old, old masters. I like the blues. I like the Carter family. Oh my God! I like A. L. Lloyd who sang those great sea shanties. I loved Jimmie Rodgers, and when I went to Japan, I got his Singing Brakeman album. There’s a song with the singing brakeman, Jimmie Rodgers, playing with Louie Armstrong. The old music, the old field recordings, the old rhythm and blues. That’s the music I grew up with. Out of the 1960s music, I liked Revolver by the Beatles.

Spirit: If we could just add that everything the Beatles did from Rubber Soul all the way through Abbey Road was the finest music of our generation, I’d be in agreement.

McDonald: Revolver is better than anything. There were a couple other things that were incredible to me: “Superstition” by Stevie Wonder. And Eat a Peach. Oh my God!

Spirit: Eat a Peach by the Allman Brothers was one of the finest albums. They did “One Way Out” by Sonny Boy Williamson and “Trouble No More,” a blues song by Muddy Waters. Duane Allman was just amazing on those songs.

McDonald: Oh my God, yes! Also, maybe Satanic Majesties Request by the Rolling Stones?

Spirit: I really loved the Stones “She’s Like a Rainbow” from that record!

McDonald: Well, that shows you. Satanic Majesties Request by the Stones and Revolver by the Beatles are the two great psychedelic albums that still hold up.

Spirit: What else did you like in the blues?

McDonald: In the 1960s, I discovered the Folk Blues recordings on Chess Records. You had the Muddy Waters Folk Blues with Muddy’s house band with Little Walter. Muddy’s house band was just great!

Spirit: Muddy dreamed up the whole idea of creating the great blues band with Little Walter on harmonica, Otis Spann on piano and Jimmy Rogers and Muddy on guitar. What other blues artists moved you?

McDonald: Blind Willie Johnson. And Robert Johnson, the inventor of rock and roll. Muddy Waters. Little Walter. But back to Blind Willie Johnson… I was listening to him just last night and oh my God — Blind Willie Johnson! And I love those early field recordings of the blues that Lomax did — some of the early blues. My favorite band in the world is the Joe “King” Oliver Jazz Band with Louis Armstrong on second trumpet (cornet). That’s the best band of all.

Blues for Bloomfield

Spirit: One of the great blues artists of the 1960s was Al Wilson who played blues harp and slide guitar for Canned Heat. He played guitar with Son House. John Lee Hooker said he was the finest harp player he’d ever worked with.

McDonald: Oh, my God. He was absolutely one of the best. And I loved the original Canned Heat. Very few white kids managed to tap into the blues in a real way and channel the blues the way the old masters did. Michael Bloomfield did it and Al Wilson did it, and we lost both of them tragically. We lost them. Without a doubt, they played unbelievable stuff.

Spirit: Michael Bloomfield was the most exceptional blues guitarist of his generation. Bloomfield and Wilson both played the blues so beautifully. In your “Blues for Michael,” from Superstitious Blues, you sang this for Michael Bloomfield:

Now your chair is empty, your guitar left untuned.

And it hurts so bad now, to not hear you play the blues.

Hey, hey, Michael won’t you play some blues for me.

To hear you play would be so heavenly.

McDonald: Yes, Bloomfield and Wilson LIVED the blues! It was a tragic blues swan dive that ended both of their lives. They suffered, both of them.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Terry Messman, a regular contributor to this site, is the editor and designer of Street Spirit, a street newspaper published by the American Friends Service Committee and sold by homeless vendors in Berkeley, Oakland, and Santa Cruz, California. Please click on his byline to view his Author’s page, for an index of his interviews and articles. Country Joe’s personal website is a lively source of information, about him, his recordings, and books by and about him.