Resistance or Christian Witness: CIMADE at Work under the Occupation

by Violette Mouchon

Editor’s Preface: This article is an unpublished English translation of an article Violette Muchon wrote for the French journal Réforme. The French original appeared in early 1945, that is, before the German surrender in April 1945. This translation was sent to WRI/London in 1951 for a proposed book on WWII nonviolent resistance, which was never published. Her translation retains the present tenses of the original French, and is a moving report from the field of extraordinary courage in appalling circumstances. We are honored to be able to post it. Further information about Violette Mouchon can be found in the Editor’s Note at the end. JG

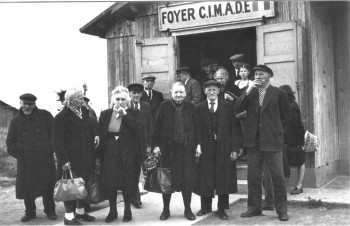

A Cimade internment camp office; courtesy of lacimade.org

Occupied France… The crooked cross on our monuments… the hand of the occupier weighing heavily, invisible, on the Vichy government.

The system of concentration camps extended over the whole of France. The German authorities are interning in the Unoccupied Zone the political refugees from Spain and those who fled from Germany and Central Europe via Holland, Belgium, Northern France, and lastly Southern France. Jewish deportees also started to flow into these camps and by 1940 the camps in the Unoccupied Zone already held more than 70,000 internees.

Now, in October 1939, the Protestant Youth Movements: the Y.M.C.A. and the Y.W.C. A., the Scouts, and the Federation of Christian Student Associations, had founded an organisation of Christian witness and assistance, The Joint Committee for Evacuees, known by the abbreviation CIMADE, which was ready to work in the areas affected by the war.

CIMADE had worked in 1940 among the Alsatians evacuated to Haute-Vienne and Dordogne. In the autumn of 1940, it was decided to carry this work into the concentration camps, beginning with the camp at Gurs. Eight thousand Jewish people from Baden, including inmates from maternity homes, old people’s homes and lunatic asylums, arrested without warning and packed into 20 trainloads of cattle trucks, had just arrived there to join the 4,000 other internees from various sources: Spaniards, suspects, soldiers from the International Brigade.

In November, our General Secretary and a female team worker presented themselves at the camp and asked for permission to look after the Protestants of which there were about 800 there at that time. Permission was given for one day a month until, growing tired of their persistence, the authorities at last gave the team permission to live inside the camp, and put a hut at their disposal.

Gurs is a village of huts 2.5 km. long, emerging from a sea of deep mud, divided into blocks by barbed wire. The huts are not heated and are without windows or light and, in the darkness, the eyes of the internees glow like night birds; straw mattresses on the bare ground (it will be necessary to wait until the Spring for bedsteads). The cooks are preparing a meal of turnips and artichokes in the open air and this, with the bread ration, comprises the whole of the diet. The internees are waiting for it outside in their ragged clothes, carrying the old jam tin, which is all they have in the way of plates or dishes. They have the waxen skin of the grossly undernourished. Hunger oedema appeared among them by March 1941, with its painful swelling. At one corner of the camp there is the cemetery, the graves standing in serried rows: for many this will be the way out.

The CIMADE hut is at one end of the camp: a big room, which is sometimes a library, a concert room, a Protestant chapel or a dining room. The first concern of our teams – two women soon joined by a young clergyman – was to form a congregation. All consolation sounds false in the ears of those who are without security, with no future, without human dignity. The Word of God alone, with the assurance of the Love, which surrounds those rejected of men, takes on a completely new value. The young clergyman takes Bible study, and three catechism classes. Ten baptisms have been celebrated, in spite of the length of instruction required.

In France nothing is known of the distress of the internees. The few who “know” cannot talk about it, much less write about it: the censorship is pitiless and any imprudent remark would risk the closing down of the work of CIMADE. Some news of the situation has filtered through abroad, from the emigrants arriving in the United States; help in money and in kind arrives. The team members, ably assisted by representatives chosen by the internees, organise “ecumenical meals” and the weekly distribution of food to 150 people. The parcels and the clothing sent by the French youth movements also relieved the misery. None of the Protestants or the “Dependants” of CIMADE suffered from hunger oedema.

Following CIMADE, other people came into the camp: the Quakers, the Swiss Save the Children organisation, Jewish organisations and, in liaison with CIMADE, the Y.M.C.A. and the European Fund for Helping Students.

By the Spring of 1941, more teams from CIMADE were working in other camps, Rivesaltes, Récébédou, Brens (suspected women). Freedom was secured for some of the inmates: CIMADE opens a home at Marseilles to meet and help the liberated people awaiting emigration. Lost in the big city, they wait for a ship, which for many of them will never come. Then the opening of the house “Coteau Fleuri” at Chambon in June 1942, which gives shelter to 70 people liberated from Gurs and Rivesaltes. The following year, it is possible to intensify the requests for liberation because of the opening of the houses at Mas du Diable, in Provence and at Vabres.

In August, 1942, a tragic event: the beginning of the big Jewish deportations. Germany demands that 20,000 Jews in the Unoccupied Zone should be delivered up. The internees from the various camps are sent to Rivesaltes, which serves as a “sorting-out” camp. Three weeks later the systematic arrest of the foreign Jews who are not yet interned started: these are sent to the camp des Milles in Provence. The French authorities, in order to discriminate between the deportees, draw up a dozen “exceptional cases”, e.g. persons over sixty years of age, mothers with a child less than one year old, those married to Aryans, etc.

The deportees are sent away in sealed wagons towards the line of demarcation, towards the unknown, towards death.

There are scenes of despair. The CIMADE teams are there, discussing each move with the police and with the prefectural services. At first, about 50 persons were snatched from each convoy of 500, a proportion, which later increased to nearly 50 percent of the convoys. If success is not attainable by legal means, escapes are organised.

But the winter is in sight. Many Jews, adults and children, are hidden in friendly lofts, in vicarages. They risk being caught at any moment. The situation cannot continue. CIMADE decides to get them across the Swiss frontier. In order that they can travel safely, it is necessary to turn them into civilians again. Our secretariat is transformed at night into a laboratory of false papers.

The first crossings, under the guidance of athletic young men, are made over the high mountains above le Buet in the middle of the snow. Then more accessible routes are found in the Annemasse region. It will be necessary finally to go as far as the Jura. The crossings are organised as follows: a member of the team goes to find the people in their refuge, in Coteau or elsewhere, and brings them to our secretariat in Nimes or Valence. They wait there for a signal from the guide team which is working on the frontier and which will enable them to cross the barbed wire at places carefully marked and changed each day. Sometimes it is necessary to climb up a wire network more than 3 metres (9 feet) high; at other times to get through timber barricades; at one spot in a wood the barbed wire is low but is a metre (3 feet) wide – the guide lies flat on his stomach on the wire and the “clients” pass quickly over his back. The business is an adventurous one. There are some arrests, as many among the travellers as among the team members. Some people are in prison for several months but come out of prison unharmed. The last crossing is made on 6th June, 1944. About 200 people have thus reached Switzerland where, on their arrival, they are followed up by the Ecumenical Council of Churches who get them accepted by the Federal Council so that they are not pushed back to the frontier. There, after a few months in a camp, they are liberated or are put into work camps.

This work put us in contact with the Resistance, and had led us to describe briefly the aims and methods we used. The Resistance had the liberation of territory as its objective, by various means, even using armed force. We maintained our work as a Christian witness. Let us develop this idea.

The fundamental motive power is to declare the Love of God, which sees in each human being a brother for whom Christ died. Bearing in mind the dignity of each man and the infinite value of each life, the Christian witness is forced to oppose dictatorial systems and violence which degrade mankind, and to save the lives threatened – but this must be done without destroying lives.

CIMADE has tried to instill in the administrative and police authorities of the Vichy Government, as well as to the Minister of Home Affairs and the prefects and camp directors, respect for the Jews, the Spanish Republicans, the Communists and the French “Gaullists”. When the lives of the Jews were threatened, CIMADE has had to work against the police and, in order to save lives, has had to use even lies and deceitful methods. This was where it met the Resistance. But it refused to use violence and has always forbidden its team members to carry arms. CIMADE saw the danger that there was in encouraging young people to lie: in the training and rest camps organised for the team members, the demands of the Christian faith were emphasised and the members were strengthened in the fidelity of their witness. It renounced all illegal action as soon as it was able to do so.

Today this fidelity of witness is leading CIMADE into a new path. It is going into the internment camps for French collaborators and interned civilian Germans to talk to them of the Love of God which is calling them to repentance and a new life. This work can only appear contradictory to our previous work to those who see only the surface. The necessity of witnessing leads us to take risky or unpopular positions, to bring to the problems the radical solutions which are God’s. Will the reconciliation of conflicting French opinions spread to others than believers who together partake of the bread and the wine at the Lord’s Supper? The Christmas celebration in Drancy among a crowd of men, many of whom were crying, has been an unforgettable witness for those taking part. And can we expect a radical change in Nazi Germany otherwise than through a return to the faith which is in Christ Jesus?

Finally, if the Christian witness is directed to all men, it is also given by all believers, to whatever race and nation they belong. We were enabled to carry on our work by the help given to us five years ago by the Christian Churches outside our country: we went to the internees in the name of the Christians in Switzerland, in Sweden and in America. During the last few weeks, the members of these churches have been arriving in France to join their witness to ours and with us to attack a new sphere of work, viz. the damaged cities. There are no rivalries and no national misunderstandings in this communion of witness. But the sense of belonging to different nations is not weakened, on the contrary. One is perhaps reminded at certain times of the vision of the Apocalypse… “I beheld, and lo, a great multitude which no man could number, of all nations and kindreds and people and tongues… and they cried with a loud voice, saying: Salvation to our God.” (Rev. 7.9.)

Reference: IISG/WRI Archive Box 148: Folder 1, Subfolder 7

EDITOR’S NOTE: Violette Mouchon (1893-1985) was the leader of Cimade (Comité Inter-Mouvements Auprès des Evacuées) in early 1945, when this article appeared in the French paper Reforme. With Jeanne Marie d’Aubigne, she is the co-author of Les Clandestins de Dieu, Cimade 1939-1945 (Paris: Fayard, 1968), in English translation as God’s Underground (Bloomington, Minnesota: Bethany Press, 1970), with thanks to WRI/London and their director Christine Schweitzer for permission.