Report on Nonviolent Resistance in the District of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, Haute-Loire, France during the War 1939-1945

by André Trocmé

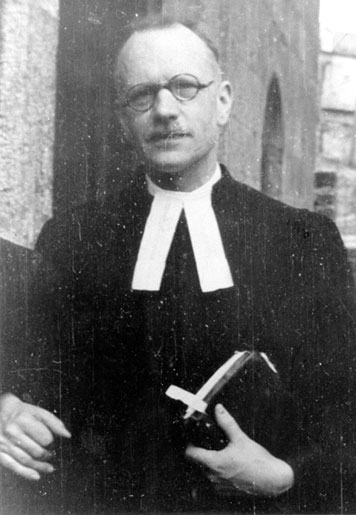

André Trocmé; courtesy yadvashem.org

Editor’s Preface: In 1952, at the WRI meeting of the International Council, the idea originated to publish a book of accounts on nonviolent resistance to the WWII German occupation. In January 1953 Grace Beaton, WRI’s General Secretary, sent a series of letters to the WRI chapters in twenty countries, asking them for personal accounts or knowledge of instances of nonviolent resistance during the war. Thirteen of these chapters replied, but only a handful of the accounts were about nonviolent resistance. The book was never published. As a consequence this article has remained unpublished until now. The most successful examples of nonviolent resistance were the reports sent from France about Le Chambon by André Trocmé, and Violette Mouchon’s account of the French youth organization La Cimade. Both paint a vivid picture of Christian pacifists who, amid horrendous violence and with great personal courage, remained loyal to their nonviolent principles. Pastor André Trocmé (1901-1971) was the spiritual leader of the Protestant Huguenot congregation in the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon in the Haute-Loire region of Southeastern France not far from the Swiss border. In the early thirties he and his wife Magda (1901-1996) had been “banished” to this remote village because of their pacifist convictions. When in June 1940 France was occupied, Trocmé urged his congregation to shelter persecuted fugitives. Le Chambon and the surrounding villages became a unique refuge place in France, where many Jews, children and entire families, survived the war. In 1971 Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Memorial Center in Israel, recognized André as Righteous among the Nations. In 1986 Magda Trocmé was also recognized. Several years later Yad Vashem honored Le Chambon and the neighboring villages and towns with an engraved stele in Le Chambon’s memorial park. Le Chambon’s and the Trocmés’ nonviolent resistance does not lessen the efforts of La Cimade. In October 1939, the YMCA, the Protestant scouting movement and the Federation of Christian Student Associations founded La Cimade (Comité Inter-Mouvements auprès des Évacués–the Joint Committee for Refugees), an organization originally dedicated to helping people who had been evacuated from the bordering provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. The goal of La Cimade, as it still is today, was to show solidarity with refugees and oppressed people by being “present” with them. During the war they did a good bit more than that, as they set up safe houses for persecuted refugees and managed to smuggle hundreds of Jews across the Swiss border. The original was written in English. Please consult the notes at the end for archival references. Gertjan Cobelens

Jewish children hidden in Le Chambon, 1942; courtesy jewishvirtuallibrary.org

The WRI Report

Spontaneously, as soon as German Military Police, Vichy Government police and the Gestapo started to arrest political refugees (singly at first, then in groups), the Jews and the young men who were hiding to avoid working for the Germans, the resistance of the population all over France manifested itself. Its very spontaneity made it invulnerable, but that is all the more reason why it is practically impossible to tell its story; for it consists of a multitude of courageous acts by individuals.

From 1943 onwards it is possible to write the history of the Resistance as soon as it became organised; but that is also the moment when it became violent in character. The exceptional nature of the resistance at Le Chambon arose simply from the fact that it had been possible to organise it in advance, and that its nonviolent nature was maintained to the end. This action would have been much more difficult had it not been for the presence of a youth group called “Cimade” (an inter-group movement for the help for evacuees) whose heroic members succeeded in arranging to send into Switzerland, under care of the World Council of Churches, a large number of Jewish refugees.

Conditions Favouring Nonviolent Resistance in the Chambon District

Totalitarian regimes and more generally the control exercised over a nation in wartime by police and censors, render it almost impossible to organize nonviolent resistance.

(a) If the resistance arises from individuals or from small isolated groups within a hostile mass, the resisters will almost inevitably be denounced, arrested and at times liquidated. One must have lived through the collective emotions created by skilful propaganda in order to understand how it is practically impossible to offer open opposition. Large towns will never be favoured ground for open nonviolent resistance.

(b) Small towns and the countryside where everybody knows everybody else seem to be more adapted for it. In particular peasants escape from the mastery exerted by radio and press; but they are timid conformists, incapable of initiative. Yet the initiative must be taken and if it coincides with the deepest thoughts of the population, the latter will give reliable and tacit approval.

(c) A religious feeling, rather than collective enthusiasm, is capable of creating that silent individual devotion which is essential to a nonviolent campaign. Those who initiate the campaign and accept the visible risk of the undertaking, cannot act without the support of hundreds of other more modest personalities.

(d) Denunciations are inevitable but the police will generally be reluctant to act when it feels public opinion against it.

All these conditions existed in the Chambon district between 1939 and 1944; seven or eight thousand Huguenots had formed a separate world there, from the time of the Reformation. It is impossible to arrest seven or eight thousand persons, so the authorities had to come to terms with them. It was outside this homogeneous group that the frontier passed, separating them with those who collaborated with the Vichy Government. However, before that oneness of purpose was reached, several stages had to be passed by which the public opinion of the Huguenot group was educated.

Jewish children sheltered in Le Chambon, 1941; courtesy U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

First stage. Opposition to the war, 1939-1944.

The beginning is always the most difficult part. After the invasion of Czechoslovakia and of Poland, it was almost impossible to say “no” to the war against Hitler. Public opinion took the two pastors of Chambon (that is, myself and Reverend Edouard Theis), who from the pulpit proclaimed their conscientious objection – for traitors, accomplices of the Nazis or at the least for dangerous fanatics; it was a time of complete solitude but happily the two colleagues understood each other perfectly in the matter of resistance.

Second stage. Search for a form of service.

The war brought in its train unspeakable suffering: refugees from Republican Spain, from Alsace-Lorraine and from Central Europe. At the time of the military collapse in 1940, after the wave of despair brought from Rotterdam by the civilian fugitives who had left parts of their families along the roads as victims of air attacks, there was an influx of fugitives.

The two pastors had seen their duty clearly as soon as the first catastrophic news arrived. It was no longer a matter of saying merely “no” to the war. The reason for their not being called up was not on account of their age, but their big families; Theis had eight children and Magda and I had four. Their co-comrades of military age were in prison; it became necessary to say “yes” to human sufferings, and to be on the spot where they were occurring. Quakers and the I.V.S.P. (International Voluntary Service for Peace) have long realized that the true pacifist witness consists in fighting evil with good. The two pastors who, on account of family responsibilities had not been called up, tried to join the International Red Cross; French Military Authorities refused them permission. The two pastors did not know that two weeks later human distress would come to them.

Third stage. Sudden change of political values, June 1940.

June 1940 brought the armistice between Hitler and Pétain, and the end of the Republic. In a few hours it had become necessary for the French to learn to burn what one had worshipped and to worship what one had burnt. That liberty for which people had fought, was presented by the new government as a cowardly lapse which had caused the defeat of France. The Nationalism against which they had fought was depicted as a noble discipline, which creates the virtues of “work, family and fatherland”. The most extraordinary thing is that few Frenchmen immediately noticed the change. Recourse was had to the experience of a few men grouped around the pastors, men who had known Nazism in Germany and who knew that it is impossible to make peace with the powers of darkness; only then was it possible once more to say “no”. The same denouncers accused the Resistance of being accomplices of England – it was at the time of Mers-el-Kebir when the British Fleet destroyed the French in the Bay of Oran (Algeria).

Fourth Stage. First signs of collective resistance.

From 1940 to 1941, three efforts were made by the Government to bring into line the Old Comrades, the churches and the French youth.

(a) Legion of War Veterans (which later became Pétain’s party). With few exceptions, all the men of the district went into it for fear of losing their jobs. Yet, inspired by the two pastors, the Chairman of the Chambon group added to the oath of obedience to the Marshall, these words: “as far as the orders I receive are in conformity with God’s will”. Nothing happened to him. Within a year the local section of the Legion had become useless for police checking of public opinion.

(b) Saluting the flag had become compulsory in all schools, together with the use of the Fascist salute. The Collège Cévenol refused to obey the order; the group of teachers who favoured the salute used to go out of the forecourt of the Protestant Church to make the salute, which was held in the playground of the primary state school. At the end of the year the custom was gradually abandoned in all the schools.

(c) Ringing of the church bells was ordered to celebrate the anniversary of the founding of the Legion. The pastors refused. In spite of the violent conduct of some women parishioners who wanted to ring the bells themselves, a small woman caretaker refused them access to the church. Those little serio-comic events contributed to the rousing of the spirit of resistance of the Huguenots.

Fifth Stage. The Jewish question 1941-1942.

For some months alarming news had been reaching Chambon about the terrible living conditions of the Jews interned in camps in the south of France. (Gurs, Argelès, les Milles). The church was very moved and decided to send one of its pastors with relief to help the social workers who were already at work in the camps. I went and found there a group of American Quakers who were still active in Marseilles at that time. They proposed that we take to Chambon any refugee children who might be got out of the internment camps.

Soon “Guespy” was opened, the first house for children; in a few months seven other houses were opened by various movements to receive the children, students and adults, a large proportion of whom were Jews. This action was undertaken quite consciously, at a time when it was already dangerous to shelter Jews. That was one fashion of burning their boats behind them and resisting constructively the fanaticism of the day. Thanks to that fraternal action, the nature of nonviolent resistance (and also its methods) became evident both to the church and to the population of Chambon.

Sixth Stage. Conflict with authorities, the summer of 1942.

Suddenly during the summer of 1942 the news reached Vichy-France of the savage operations in Paris against the Jews. That was the moment chosen by the Minister for Youth, M. Lamiraud, to pay a visit to the young Protestants of Chambon to rally them around Marshal Pétain.

Conflict broke out because of two factors:

(a) The establishment of the youth movements. Through the decision of the local leaders of the Youth Movement the visit was informal and had no official character; as people were leaving a religious service, a delegation of thirty from the Collège Cévenol (a secondary school with a Christian pacifist outlook, founded at Le Chambon in 1933. In 1942 it had 300 pupils) went up to the Minister and the Prefect who was accompanying him, to protest solemnly against the anti-Semitic persecutions and to state that if the raids had taken place at Chambon the young people would have opposed it nonviolently. The Prefect was indignant and while admitting having received orders, repeated the official theme: “there is no question of persecution but of a re-grouping of the population of the Jews in Poland. Then, turning towards the Pastors the Prefect declared: “Beware! I have received letters from seven denouncers and I know all your doings and gestures.” That very week the youth groups were called together by the Pastors to set up a hiding place for the hundred or so Jews who were in the village.

(b) The other factor was the order to round up Jews in Chambon and the surrounding districts, and a real storm broke out when Vichy police came and occupied the village. Two big coaches intended to carry off the Jews were parked in the village square. The Pastors were called upon to give a list of the Jews in the village. On their refusal they were urged to sign a notice calling on the Jews to give themselves up so as to not disturb public order and not to endanger the families, which were sheltering them. Again the pastors refused. They were then threatened with arrest if the order had not been carried out by mid-day the next day, Sunday. Instead of obeying the order, they put into action that same night the plan arranged for the “disappearance” of the Jews. The Protestant church was full that Sunday morning, everybody expecting the arrest of the Pastors. The Village Council was in session under threats and signed the notorious appeal to the Jews. At noon, not a single Jew appeared. The Pastors were not arrested and forty policemen searched in vain every house in the village. They arrested one solitary Jew and put him into one of the big coaches; the people filed by, loading him with presents!

The police were stupefied, realizing they were by no means popular. The next day they had to release the prisoner, whose ancestry was but half Jewish. The policemen remained for three weeks in the village, very zealous at first and naively convinced of the rightness of their action; but they soon lost all enthusiasm. The population was educating them in the houses where they went to search and question. For long months following this, Le Chambon and the surrounding villages were raided many times by the police. Very often, on the eve of a search, an unknown voice would telephone to warn of the danger. It was undoubtedly that of a civil servant who had been converted by the nonviolent resistance of the villagers.

Seventh Stage. Development and perseverance put to the test.

The success of the methods employed at Le Chambon attracted an ever increasing flood of Jewish refugees; there were soon several hundreds of them. The Jewish Relief Agency states that more than two thousand of them stayed temporarily in the region, hidden in the farms. That was when “Cimade” came into the picture. It provided the Jews with false identity papers which were essential to avoid the regular police checks, to obtain ration cards and to be able to travel in the company of a young girl volunteer as far as the barbed wire of the Swiss frontier. There were very few arrests to deplore. A spirit of prayer surrounded the refugees, some speaking of miracles, some of greater leniency on the part of the authorities. Such leniency, however, was not evident in other parts where, on the contrary, things went from bad to worse. The protesters in the Chambon district did not hide their activities from the authorities. They merely prevented identities being known, and in the end the police shut their eyes. But the Vichy Government was not satisfied. In the spring of 1943 it ordered the Prefect to arrest the two Pastors and the Headmaster of the village school; all three were interned. After six weeks the Pastors were offered their liberty if they would swear fidelity to Pétain. They refused, but Pierre Laval, who headed the government, ordered their liberation in spite of that.

Eighth Stage. Beginnings of Violence, 1943.

It was then that for the first time the Pastors were contacted by the representatives of the Resistance Secret Army (Maquis). While expressing their sympathy, they made quite clear the difference in aims (national liberation for the Maquis, the defense of man for the others) and our difference in methods (armed resistance for the Maquis, nonviolent non-collaboration for us). The two sets of actions continued side-by-side, often intermingled, right up to the Liberation. It is difficult to say if the Maquis protected the nonviolent groups, or if the latter saved the Maquis in Haute Loire from the tragic fate of the Maquis in the Vercors Massif mountain region.

In any case the nonviolent side raised no questions about keeping their hands clean or of dissociating themselves from those who, like themselves, were bravely risking their lives. Neither did the Maquisards accuse the nonviolent ones of cowardice in spite of the fact that the latter often resisted them. In the beginning of the summer of 1943, one of the students’ homes for refugees was raided by the Gestapo who arrested the Director and 23 students. Except for three of them they all died in extermination camps.

Violence broke out on the day when four Maquisards assassinated a Vichy policeman, who had been spying on the violent and nonviolent activities of the Resistance. The Pastors publicly expressed disapproval of this act, but were held responsible by the Gestapo and condemned to death. Some of the supposed spies serving the Gestapo in fact spied on the Gestapo on behalf of the Resistance. An indiscretion on the part of a “supposed spy” gave them warning and they were able to go into hiding, where they had to stay for ten months.

During their absence the church passed through a wonderful period. The movement had spread throughout the district, although many people did slide towards armed resistance.

Ninth Stage. Resistance to the Resistance, 1944.

From the time of the Normandy Landing, while Pastor Edouard Theis continued the service of getting people across the Swiss frontier, I went back to Chambon. The whole region had come under the authority of the 4th Republic (Gaullism). The situation was extremely complex: raids by German troops, shooting of the inhabitants of certain villages, burning of houses, all caused great emotion among the over-excited people.

Allied planes parachuted arms during the night and many among the youth of the church and village joined the Maquis. A few preferred to remain nonviolent and served in other ways. Spying was prevalent for a time and the Pastor member of the Liberation Committee opposed the execution of suspects. He was not called to any further meetings, but the lives of the suspects were saved.

Six weeks before the Liberation, almost without firing a shot, the Maquis made prisoners of 120 Germans who were trying to get to Lyon across the mountain. They were the German Regional Commander, his staff, some Gestapo officers and some privates. They were brought to Chambon and imprisoned in a country house. This was the time when the story of the Oradour massacre was being circulated, when every German was held responsible for the crime. All 600-700 inhabitants of this small village, men, women and children were rounded up by the Waffen-SS and massacred, so emotions were high. The Pastor made himself unpopular with the Maquisards by visiting the prisoners. At first none of the prisoners felt guilty, for they believed in the early victory of Hitler, looking on themselves as innocent victims of Communist terrorist freeshooters. On Sunday mornings, in a full church, the Pastor preached strong sermons to those Maquisards present and in the afternoon the same sermon, translated word for word, was repeated to the Germans. On both sides conscience was roused and rarely has the evidence of the Gospel of Peace been so striking. When sounded the hour of the Liberation, the popularity of the Pastor was not great, but the moral destruction caused by joining violence to the Gospel had been avoided. In addition many lives had been saved.

Tenth Stage. Two martyrs, 1944.

This last stage was passed through by two men alone.

My nephew, Daniel Trocmé, professor, Headmaster of two homes for refugee children, after a year of untiring devotion, was arrested in 1943, at the same time as his Jewish students. Held a prisoner, he continued to defend the Jews and was identified with them by the Gestapo. He died in the concentration camp at Majdanek, Poland, probably gassed, in the spring of 1944.

Roger Le Forestier, a doctor at Chambon, arrested after an imprudent step taken by the Prefecture, gave so powerful a witness for nonviolent Christianity before the Regional Commander, that he was let off, but required to go to Germany as a “volunteer”. He again fell into the hands of the Gestapo at Lyons while being transferred to Germany, and was massacred with 120 other innocent victims.

It is certain, according to the declarations of the German Commander, that Le Forestier’s words on the nonviolent character of the resistance in Chambon, encouraged the Germans to spare the region where so many children and innocent people had gone for refuge.

Conclusion.

One cannot draw from the successes of the nonviolent resistance at Chambon any lesson of a line of conduct, which would inevitably ensure success. Similar circumstances are never repeated.

On the other hand, the attempt at resistance in the Chambon district was very imperfect. Rarely during the course of it did those taking part have a feeling of a dazzling success. Only when it was all over, when trying to evaluate what had happened to them did they feel obliged to thank God for the daily proof He had given of His existence, and of His intervention in human affairs as soon as a few men place complete confidence in Him. On one point the experience was unsatisfying; it was not possible for nonviolent resisters to avoid using false identity papers. To show a true identity paper was the equivalent of a denunciation. It seemed to us preferable to violate a formal moral rule (absolute truth), in order to apply a living moral rule (the absolute value of the human person). Jesus preferred to violate the Sabbath in order to help the men of His day. Yet we are not happy about what was after all a concession to a lie.

On another point our experience was positive: to resist war is but half our duty; saying “no” to evil is not enough. War resistance must include something else – and that something else is the salvation of the physical and moral life of mankind threatened with a double destruction. And that salvation is better assured by nonviolent resistance than by violent resistance. Nonviolent resistance also has its martyrs – it also has its failures. We have never been able to console ourselves from having been unable to save the lives of twenty students of the Maison des Roches. And yet we ask ourselves how much ruin and mourning would have been caused if the two Pastors and the Christians of Chambon had felt obliged to lay ambushes and throw “plastique” bombs on the German policemen as they went through.

Let us leave aside the problem of national liberation – Gandhi alone could deal with it. Yet we can imagine a Europe which is entirely nonviolent offering total resistance to Hitler, a Europe which the Dictator and his police would have been unable to conquer.

Reference: IISG/WRI Archive Box 148: Folder 1, Subfolder 7.

EDITOR’S NOTE: With thanks to WRI/London for their generous permission making our WRI Project possible, and especially to their director Christine Schweitzer.