by Paul J. Plumitallo

Dust wrapper art courtesy amazon.com

Paul J. Plumitallo: I was wondering what violence means to you? Can violence be more than physical? Is language ever violent? There have been some disagreements about what violence actually means in my class.

Kay Bueno de Mesquita: I believe that violence is more than physical. It can be internal as well as external: violence of the spirit, a range from psychological to emotional from mild to severe. The damaging words that someone can say can have a longer lasting harmful effect than physical violence.

Plumitallo: Do you consider yourself to be nonviolent? How does one apply nonviolent principles to their daily life? We often discuss how difficult nonviolence is in our society because we are so exposed to violence.

Bueno de Mesquita: It’s true that being nonviolent in all aspects of life can be difficult. In his first principle of nonviolence Martin Luther King Jr. states that, “Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people.” [Please see the text of all Six Principles at the end of the interview.] Dr. King also said, “I’m not nonviolent some of the time, I’m nonviolent all of the time.” I strive to be nonviolent in every aspect of my life including thinking kind thoughts about myself, and others; being compassionate and empathetic to all people. I’m not always successful. But I try. I try to be mindful each day and “wake up each morning with a prayer and a smile.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Arvind Sharma

Gandhi poster courtesy rishikajain.com

Truth and nonviolence are generally considered to be the two key ingredients of Gandhian thought. It is possible to pursue one without the other, possible, for example, to pursue truth without being nonviolent. Nations go to war believing truth is on their side, or that they are on the side of truth. The more sensitive among those who believe truth is on their side insist not that there should be no war but that it should be a just war. The most sensitive, however, and pacifists are among these, avoid violence altogether. But it could be argued that in doing so they have gone too far and have abandoned truth, and even justice. Although he was opposed to war, Gandhi argued that the two parties engaging in it may not stand on the same plane: the cause of one side could be more just than the other, so that even a nonviolent person might wish to extend his or her moral support to one side rather than to the other.

Just as it is possible to pursue truth without being nonviolent, it is also possible to pursue nonviolence without pursuing truth. In fact, it could be proposed that a disjunction between the two runs the risk of cowardice being mistaken for, or masquerading as, nonviolence. The point becomes clear if we take the world “truth” to denote the “right” thing to do in a morally charged situation. Gandhi was fond of quoting the following statement from Confucius: “To know what is right and not to do it is cowardice.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Mohandas K. Gandhi

School of Andries Cornelis Lens, “Truth Protecting Us with Her Shield”, c. 1750; courtesy wikigallery.org

Editor’s Preface: “Truth”, “lies”, “alternate facts”, “post-truth politics”, etc., are terms very much in the air these days. Gandhi had much to say about Truth; the selection below is only a small sample focused on the root concepts behind his use of the term, and by application the root of his theory of nonviolence. This is the first of a series of articles we will be posting over the next few months on truth and truth in politics. Other statements on Satyagraha and Truth can be found on our Quotes and Sources page, via the link at the top of the page. JG

(I) The word Satya (Truth) is derived from Sat, which means ‘being’. Nothing is or exists in reality except Truth. That is why Sat or Truth is perhaps the most important name of God. In fact it is more correct to say that Truth is God, than to say that God is Truth. But as we cannot do without a ruler or a general, such names of God as ‘King of Kings’ or ‘The Almighty’ are and will remain generally current. On deeper thinking, however, it will be realised, that Truth (Sat or Satya) is the only correct and fully significant name for God.

And where there is Truth, there also is true knowledge. Where there is no Truth, there can be no true knowledge. That is why the word Chit or knowledge is associated with the name of God. And where there is true knowledge, there is always bliss (Ananda). There sorrow has no place. And even as Truth is eternal, so is the bliss derived from it. Hence we know God as Sat-Chit-Ananda, one who combines in Himself Truth, knowledge and bliss. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Dyllan Taxman

A drawing of Jim Forest in prison made by his son Ben, age six at the time, for his Sunday School class.

Editor’s Preface: Dyllan Taxman, an 8th grade student in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was doing a research project for his history class and decided to look into an act of civil disobedience that had taken place in his city in September 1968. As Jim Forest has written, “The Vietnam War was raging. A group of fourteen people broke into nine draft boards that had offices side by side in a Milwaukee office building, put the main files into burlap bags, then burned the papers with homemade napalm in a small park in front of the office building while reading aloud from the Gospel. We awaited arrest, were jailed for a month, freed on bail, then tried the following year, after which we went to prison for more than a year; for most of us it was 13 months.” The interview was conducted in February 2006. Please see the note at the end for further information. JG

Dyllan Taxman: What made you do this?

Jim Forest: I had been in the military myself so didn’t have to worry about the draft, but as a draft counselor (a big part of my work with the Catholic Peace Fellowship) I was painfully aware of how thousands of young people were being forced to do military service in an unjust war about which they knew little or nothing, or even opposed. Anyone who knew the conditions for a just war could see this war did not qualify.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

Photograph of the Milwaukee 14 courtesy Jim Forest; details at the end of the article.

Editor’s Preface: Tactics define a protest, whether violent or nonviolent. They have been and are a matter of controversy and heated discussion within movements, as in the recent Occupy. Indeed, some would define nonviolence as a tactic, a definition not accepted by all. In the Catonsville Nine and the Milwaukee 14 protests the burning of draft files was seen by some as a justified means towards ending the Vietnam War, while others such as Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton saw it, at the very least, as a dangerous blurring of the line between violence and nonviolence. Jim Forest is here adding his word to this debate. We have also posted other articles concerning the definition of nonviolent tactics, especially Dorothy Day’s famous article, “Dan Berrigan in Rochester”, and the book review at this link of a recent history of the Catonsville Nine, which quotes Merton’s famous warning. JG

I was one of the Milwaukee 14, a group that burned draft records in 1968. This was the action that followed the Catonsville Nine. The discussion of Plowshares-style property damage and destruction in the November issue of The Catholic Agitator really got me thinking. One of the essential elements in property destruction actions is secrecy. If you tell them you’re coming, they won’t let you in. It’s that simple. The only way around it is to take pains not to be expected. You are obliged to be secretive. There are events in life where secrecy is necessary, even contexts in which life-saving actions are difficult or even impossible unless there is secrecy. For example here in Holland, my home since 1977, you had to be highly secretive about the people you were hiding during the period of German occupation.

Read the rest of this article »

by Ken Butigan

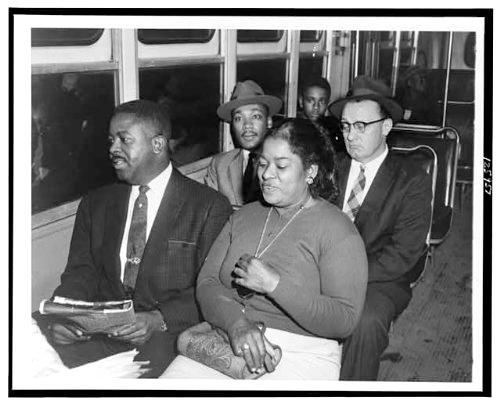

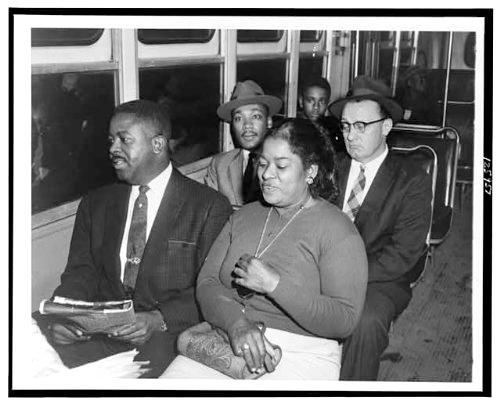

Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King, Smiley and unidentified woman, 1956 Bus Boycott; courtesy wagingnonviolence.org

During a visit years ago to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, I spent a lot of time at an exhibit where you could track the heredity of rock bands. Monitors displayed a family tree detailing what groups had influenced which bands. You could trace how particular acts had inherited, adapted or transformed genres, styles and musical innovations. For example, the Rolling Stones, to the best of my foggy recollection, were influenced by Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, and Buddy Holly, as well as by Roy Orbison and the Kingston Trio. If even one of those ancestors was out of the mix, the Stones might have sounded very different — or maybe wouldn’t have formed in the first place.

Read the rest of this article »

by Glenn Smiley

Glenn Smiley riding on a bus with Martin Luther King, Jr., 1956; courtesy wagingnonviolence.org

Editor’s Preface: Rev. Glenn E. Smiley (1910-1993) had made a thorough study of Gandhian nonviolence (satyagraha) while serving as a Methodist minister in Los Angeles. He later worked for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and was national field secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). During World War II he went to prison for conscientious objection, but he is best remembered for his work with Martin Luther King, Jr. during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Please also see the note at the end for further information, acknowledgments, and links. JG

From the beginning of humankind’s time on the earth, for about 250,000 years, conflicts between individuals and groups have been settled on the basis of force, domination, or submission. In time, the use of force became more or less institutionalized, and continues to this day in many places.

Read the rest of this article »

by Richard B. Gregg

The Wheel of Integral Non-violence is courtesy of chico-peace.org

Editor’s Preface: This 1941 article, with its Foreword by Gandhi, continues our series of important historical documents on the theory and history of Gandhian nonviolence. Gregg here argues for the value of manual labor, as advocated by John Ruskin, and as practiced by Gandhi in his ashrams, where Gregg had lived. Gandhi considered spinning and weaving essential to the routine of a nonviolent community, yet this article is one of the very few to try to explicate this. Please also see the Editor’s Note at the end for more information about Gregg, and please also consult his other article, which we have posted here. JG

Foreword (by M. K. Gandhi): ‘A Discipline for Non-violence’ is a pamphlet written by Mr. Richard B. Gregg for the guidance of those Westerners who endeavour to follow the law of Satyagraha. I use the word advisedly instead of ‘pacifism’. For what passes under the name of pacifism is not the same as Satyagraha. Mr. Gregg is a most diligent and methodical worker. He had first-hand knowledge of Satyagraha, having lived in India and then too for nearly a year in the Sabarmati Ashram. His pamphlet is seasonable and cannot fail to help the Satyagrahis of India. For though the pamphlet is written in a manner attractive for the West, the substance is the same for both the Western and the Eastern Satyagrahi. A cheap edition of the pamphlet is therefore being printed locally for the benefit of Indian readers in the hope that many will make use of it and profit by it. A special responsibility rests upon the shoulders of Indian Satyagrahis, for Mr Gregg has based the pamphlet on his observation of the working of Satyagraha in India. However admirable this guide of Mr. Gregg’s may appear as a well-arranged code, it must fail in its purpose if the Indian experiment fails. (Sevagram, 24-8-1941)

A Discipline for Non-violence

For ages military discipline has won and held men’s faith. However crude, indiscriminate, and brief may be the results of organized violence, the world still has immense respect for its show of firmness and order. Much as we dislike war, when we begin to ask how we can attain justice and peace, we come face to face with this power of the military method. What is the secret of this power? Does it lie merely in men’s fear of violence?

Read the rest of this article »

by Tom Gibian

Sandy Spring School, 2nd Grade Art Work; courtesy grover.ssfs.org/~ksantori/art/2nd_grade.htm

One of the underlying principles of Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence is our capacity for interconnectedness, or as Gandhi was to state it, “the interconnectedness of all beings.” Interconnectedness, or connecting, is also very much at the heart of Quaker concerns.

I remember being in third grade and having to line up and pair off with a classmate to walk down the hallway to some destination beyond our classroom. At Sherwood elementary school, there might have been 29 or 30 nine-year-olds and one teacher. On the day I’m recalling, I was paired off with a kid named Sammy. I was new at Sherwood and someone warned me that Sammy had sweaty palms. As we headed down the hallway, he took my hand. His hand was sweaty, but it didn’t matter. We held hands without embarrassment. We were not self-conscious. We were little, at least relative to the world we were living in, and it could not have been more natural to reach out, to partner, to connect. Later, Sam would be one of the first friends of mine to get a high-performance muscle car in high school. That is a different story!

Read the rest of this article »

by Thomas Weber

Cover art courtesy University of Minnesota Press; upress.umn.edu

As a university student with an interest in existential philosophy, I remember struggling with Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. At times there were even consecutive pages that made sense to me, but more often there were only single paragraphs separated by many pages of dense language and philosophical concepts that were beyond my comprehension. I was very thankful when I came across Sartre’s essay “Humanism as an Existentialism” and suddenly what he was trying to say came into focus and made sense. How much I lost by not comprehending the probably profounder text, I will never know. Readers of some of the latest scholarly offerings in the attempts to understand the life and thought of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi may find themselves in a similar position while waiting for the simpler more readily graspable versions to materialise. But then, weighty philosophical concepts are weighty philosophical concepts and possibly they are not meant for a wider audience that has little desire or ability to engage in deep theoretical philosophical discourse.

Once, writings about Gandhi were biographies, often hagiographical (for example by Louis Fischer); personal reminiscences, usually hagiographical (for example by his most well known British disciple Mirabehn); and selections of the Mahatma’s thoughts grouped in various categories, generally selected by those who were followers (R.K.Prabhu and U.R.Rao, Anand Hingorani, N.K.Bose and Krishna Kripalani come to mind). Of course there were serious attempts at analysing Gandhi’s campaigns through primary archival sources (for example by Judith Brown) and more probing attempts to make sense of his world view and what led him to have it (here one could list Gopinath Dhawan, T.K.N.Unnithan and Erik Erikson). During 1969, the Gandhi birth centenary year, dozens of books appeared. More recently, although there was the occasional controversy (particularly over the writings of James Lelyveld and Jad Adams), it has become almost fashionable to ensure that Gandhi scholarship can in no way be seen as hagiographical, with writers doing their utmost to undermine the “myth of the Mahatma”, by pointing out Gandhi’s inconsistencies, his youthful elitist and even racist attitudes (for example by Desai and Vahed), his older-age, controversial experiments in sexuality, and even labelling him as a traitor in the project of the creation of modern India (too many to mention). Even more recently, however, there has been another trend where scholars with a strong theoretical bent and deep philosophical knowledge have taken the Mahatma seriously and decided to turn their attention to his life and an analysis of his praxis (and here we could mention the writings of Vinay Lal, Faisal Devji, Isabel Hofmeyr and Tridip Suhrud among a growing cohort). Ajay Skaria’s Unconditional Equality: Gandhi’s Religion of Resistance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016) is a prime example of this development.

Read the rest of this article »