by Terry Messman

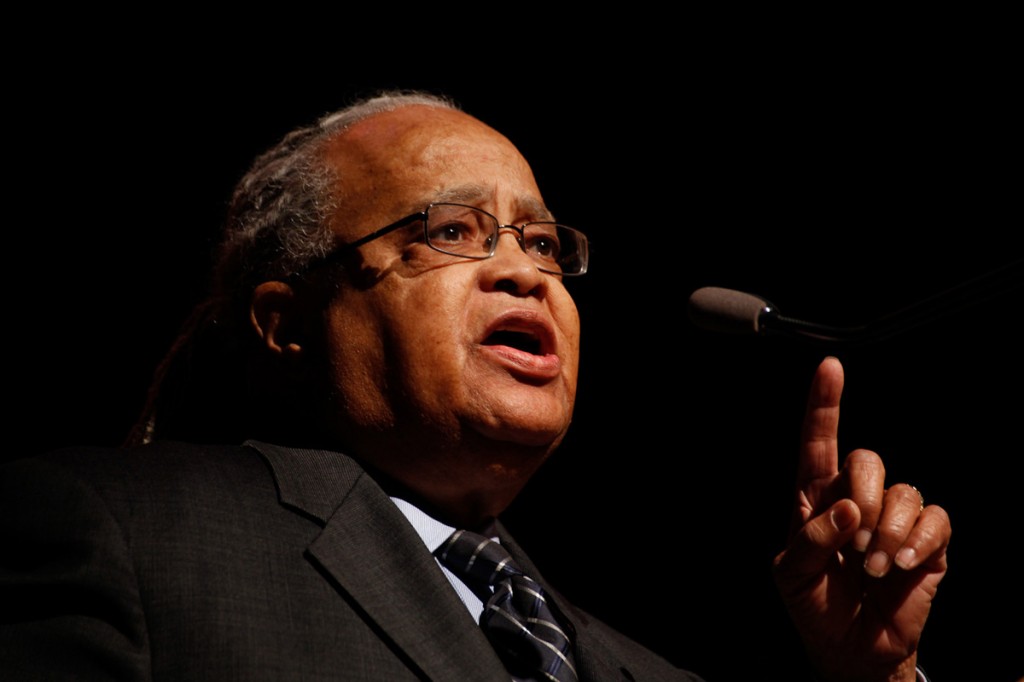

Rev. Phillip Lawson, c. 2012; photographer unknown

“Love and compassion are what sustain me. Love and you can learn how to live. I told the Council of Elders this. When you are down and depressed, or hurting or grieving, the most powerful thing you can do to sustain yourself is to go do something for someone else who is hurting.” Rev. Phil Lawson.

Street Spirit: Rev. Lawson, you told me that when you were growing up, you realized that horrific violence was directed against the black community — Jim Crow laws, segregation, lynching. In the face of that violence, why did you make a commitment to nonviolence at age 15 that has lasted for the past 65 years?

Nonviolence is a way of life that leads to community.

Rev. Phil Lawson: I’m firm in my understanding and beliefs, Terry, that nonviolence is a way of life. Rather than a tactic or a strategy to overcome problems, nonviolence is a way of life that leads to community. You cannot build community on violence, whether it’s psychological violence, economic violence, cultural or environmental violence. Regardless of the adjective you put before the word “violence,” violence will not produce community. And the goal of my life, and I think for most human beings, is community. The opposite of slavery is not freedom, but community. The opposite of abuse and oppression is not just to be free of that, but to live in a community where that abuse is infrequent, where that is not supported, where that is not structural. We live in a nation in which violence is structural; it is not personal. Racism is structural.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

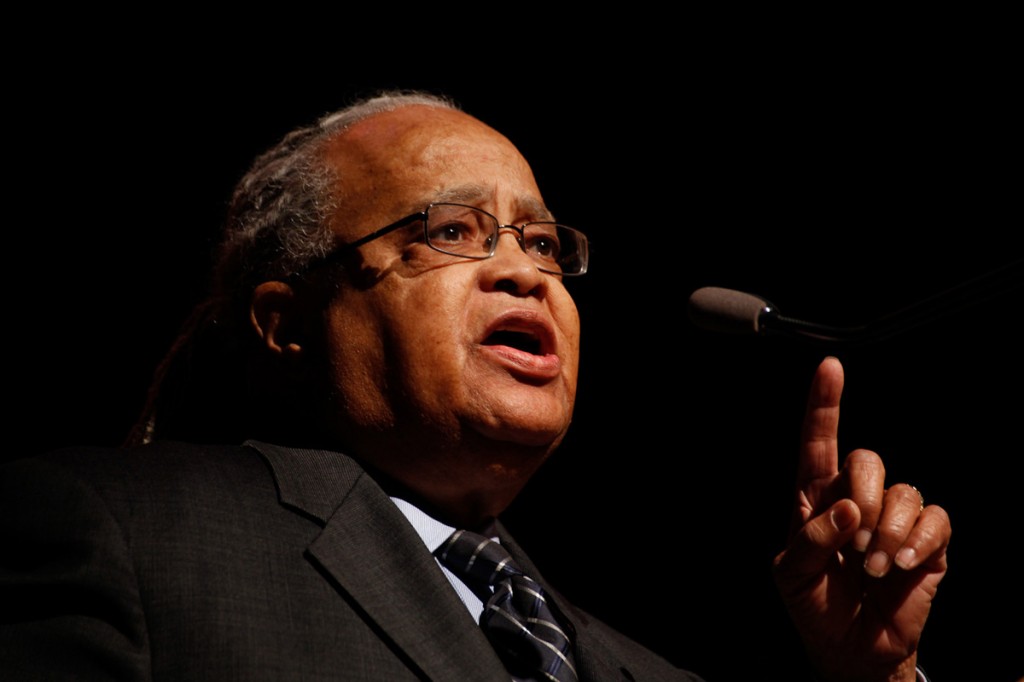

Rev. Phil Lawson rallying support for gays and lesbians; photograph by Mike DuBose.

Rev. Lawson has worked his entire life to ensure that there will be room enough in the beloved community so no one will be left outside to suffer and die in poverty on the streets, no one will be locked out by border walls, and no one will be denied entrance because of racial intolerance or homophobia. At some point in the course of his lifelong work to build a truly inclusive community, Rev. Phil Lawson became a pastor for all the people. His ministry now extends far beyond the walls of the Methodist churches where he ministered to his congregations in Richmond, El Cerrito and Vallejo. The walls of his church have expanded to include the homeless and hungry people cast out of American society, the refugees from war-torn lands in Central America, the same-sex couples he joined in marriage, the low-paid workers in Richmond struggling for living wages, the peace and justice activists who look to this soft-spoken man for leadership, and the Occupy activists seeking to build a nationwide movement for justice.

The purpose of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community.

As Lawson’s ministry has expanded through all these years of pastoral service and nonviolent movement building, it has become clear that there is only one edifice large enough to provide sanctuary for all the people he has included in his ministry — the “beloved community.” At a forum on nonviolent resistance held at the height of the Occupy movement in Oakland on Dec. 15, 2011, Rev. Lawson declared: “The end result of nonviolence is redemption and reconciliation. The purpose of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community.”

Read the rest of this article »

by David Hartsough, Sherri Maurin & Rev. Brian Woodson

David Hartsough

Phil Lawson is a lifelong peace and justice activist who works for the radical transformation of our society, towards one where every person can live with dignity. He is willing to struggle and even go to jail for his beliefs. Because he lives by the values and principles of nonviolence in his own life, Phil is an example of what a good Christian pastor should be. In the struggle to build a just and peaceful society and world, he has helped the church to become a headlight instead of a taillight. His longstanding work for real immigration reform is a model for how the churches can stand on the right side of justice. Phil’s commitment in establishing the Interfaith Tent in support of the Occupy movement in Oakland is a great example of his relentless persistence. He has that sparkle in his eye, and you know that he means what he says and that hope will always have the last word.

Read the rest of this article »

by Christian Bartolf

Four times Gandhi offered his services to the army: in 1899-1900 during the Boer War, in 1906 on the occasion of the so-called Zulu Rebellion, in 1914 during his stay in London at the outset of World War I; and lastly in India in 1918 near the conclusion of that war. After World War I Gandhi on a number of occasions was asked how he could reconcile his participation in war with his principle of nonviolence (ahimsa). Bart de Ligt was not the only person to correspond with Gandhi on this issue, but he was the most forthright and compelling. Leo Tolstoy’s friend and secretary, Vladimir Tchertkov, had also questioned Gandhi about it. In fact, it was a common reverence for Tolstoy’s doctrine of non-resistance or non-violent resistance that was the foundation for the critical dialogue between Bart de Ligt and Gandhi between 1928 and 1930. As an introduction to this correspondence, we shall first summarize Gandhi’s participation in various wars, and the exchanges of letters and conversations, which Gandhi had on this matter, including his dialogue with Bart de Ligt.(1)

Read the rest of this article »

In the years immediately following World War I, Western pacifists were seeing with alarming clarity the possibility of another war, and speaking out with increasing urgency against militarism. Having suffered through the trauma of appalling destruction, pacifist writing in the 1920s and 1930s has the aura of a survival myth. The advent of Gandhian satyagraha presented pacifists with a possible strategy for averting tragedy, as an antidote to war, and moved Bart de Ligt to write publicly and openly to Gandhi, to enlist him in the pacifist cause. Gandhi’s nonviolence was never a fixed principle; was ever evolving. The Salt March of March 1930, which some see as pivotal to the development of Gandhian nonviolent resistance, had not yet taken place when these letters were published. On the one hand, there are pacifists determined to staunch the advent of another daimonic war, and on the other hand there is Gandhi in a death struggle with the British for Indian independence, his nonviolence, by his own admission, imperfect. De Ligt’s call for Gandhi to reject war, to commit satyagraha to the ending of war was a prophetic call. [JG]

Letter One: Bart de Ligt to Gandhi; May, 1928.

Most venerated Gandhi:

Without doubt, there is no man who attracts the attention of the modern world as you do. And you are certainly worthy of this admiration because you have been able in a wise, heroic way to awaken everywhere confidence in that moral force which slumbers in each individual. To oppose the severe oppression of so-called Christian civilization, and the violence of proud and pretentious Westerners, you have awakened in the East immense spiritual forces, making it seem that Christ reigns over your “pagan” world rather than in our official Christian churches. You have not only proclaimed the gospel of non-resistance — or spiritual warfare — but you have yourself practiced it and have paid with your own person.

Read the rest of this article »

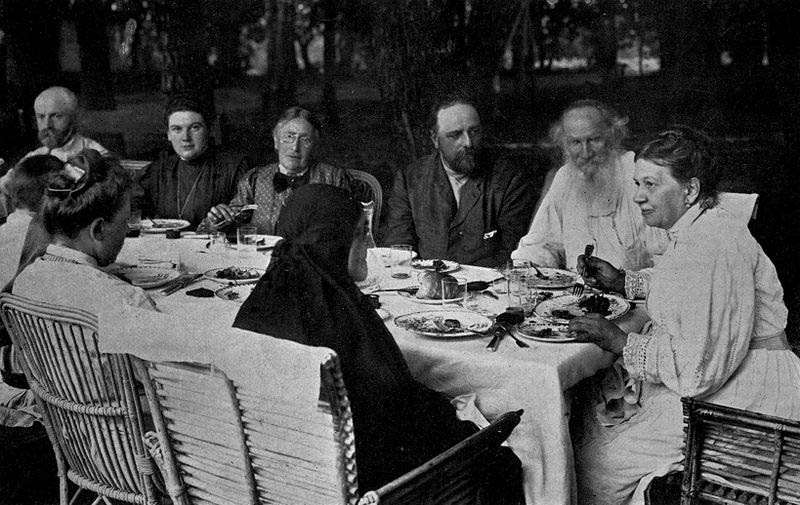

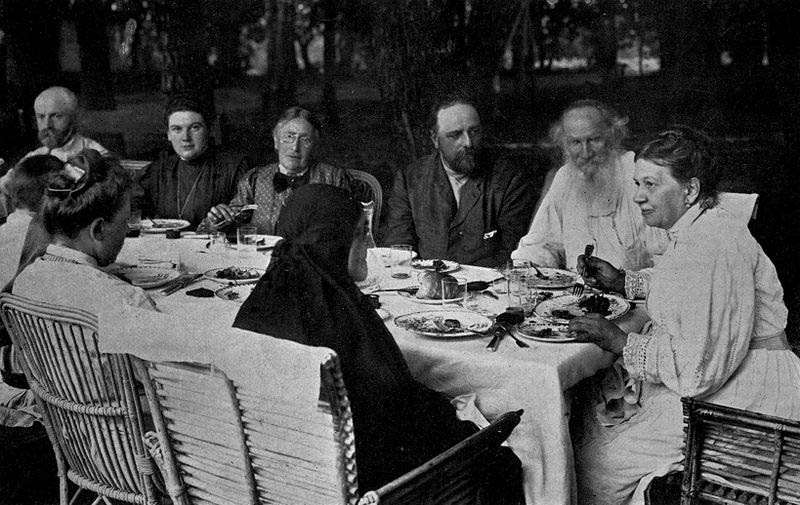

Tolstoy family gathering, 1905; Tchertkov to Tolstoy’s right; photographer unknown.

My article, “My Attitude Towards War”, published in Young India, 13th September 1928, has given rise to much correspondence with me and in the European press that is interested in war against war. In the personal correspondence there is a letter from Tolstoy’s friend and follower, V. Tchertkov, which, coming as it does from one who commands great respect among lovers of peace, the reader will like me to share with him. Here is the letter:

Personal Letter from Vladimir Tchertkov

Your Russian friends send you their warmest greetings and best wishes for the further success of your devoted service for God and men. With the liveliest interest do we follow your life, the work of your mind, and your activity, and we rejoice at each of your successes. We realize that all that you attain in your own country is at the same time also our attainment, for, although under different circumstances, we are serving the one and the same cause. We feel a great gratitude to you for all that you have given and are giving us by your person, the example of your life, and your fruitful social work. We feel the deepest and most joyous spiritual union with you.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bart de Ligt

From Germany, Austria and other countries, I have been urged for information about my correspondence with Gandhi, which so far has only been published in French, English and Dutch and for various reasons could not be published in German. I am therefore most grateful to the editorial staff of Neue Generation (New Generation) for the opportunity to acquaint you with a few matters.

It was only in 1928 that I could really go more profoundly into Gandhi’s life. I had read, of course, with great interest a number of his articles. As well as that, I had taken note of various articles written about him. The most important insights I owe to the short book by Romain Rolland (Mahatma Gandhi, 1922) and a few articles published in magazines.

From these I came to understand Gandhi as the legitimate follower of Tolstoy. Whereas Tolstoy would have been the “John the Baptist” of revolutionary nonviolence, Gandhi would have been the Christ, so to speak, of this movement; Tolstoy the Great Precursor and Prophet, Gandhi the Performer fulfilling the Prophecy.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bart de Ligt

At the Congress of War Resisters, held in Lyons, August 1931, Tolstoy’s last secretary, Valentin Bulgakov spoke of the “great experience” gained by India in its struggle against England. Not without reason did he express admiration for the role Gandhi played in this struggle. But Bulgakov tended to attribute to the Mahatma an attitude that was consistently hostile to any sort of violence, an attitude which, according to Gandhi himself, does not correspond with the facts.

In Le Semeur of October 15th, 1931, Bulgakov also declared that the correspondence which Vladimir Tchertkov and I have had with the Indian leader, regarding Gandhi’s attitude during the Boer War, the Zulu-Natal War and the World War, concerns only “a few ill-advised declarations” of Gandhi, “purely accidental” and remaining “without effect; Gandhi’s actions demonstrating that he in no way approves of cooperation with violence.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Richard Gregg

Those who are familiar with Gandhi’s life will recall that up to 1919 he believed that the British Empire did more good than harm to the world and to India. He had not then evolved his program of hand spinning and weaving, nor in his South African struggles had he used the boycott or refusal to pay taxes as political weapons. He has stated that up to that time he did not have strength to resist war effectively.

Richard Gregg, c. 1930s, photographer unknown; courtesy Quakers in the World.

Therefore, I think that he did war service because up till then he did not realize the extent of violence and untruth inherent in the State; he did not fully understand the complex and subtle nature of its control over people; and had not yet devised practical methods of ending that control. Nevertheless, he knew that war is only a result, a final stage of a psychological process that begins with fear, anger and greed. In organized social life most of us support the State by paying taxes, by buying articles from people or corporations that similarly support the State, and by not effectively helping others to escape this domination. To refuse military service after taking part in all this is merely to lock the stable door after the horse is stolen. Gandhi seems to have preferred to take some part in war to see if somehow he could render good for evil. Innocent or inconsistent perhaps, but with deeper understanding than that of most.

Read the rest of this article »

by R. A. Jayantha

The impressive popularity achieved by some of the novels of R. K. Narayan, notably The Financial Expert, The English Teacher and The Guide, seems to have somewhat obscured his significant achievement in The Vendor of Sweets (hereafter abbreviated to The Vendor).

Cover art, Penguin Classics edition; photograph by Abbas/Magnum.

A creation of his ripe age and maturity as novelist – Narayan was sixty at the time of writing this work – it has a subtle charm, which becomes apparent to the reader only after a second or third reading. At least, it was so with me. In terms of outward events, dramatic and sensational happenings, and variety of people, The Vendor is a complete contrast to his other novels. It is outwardly quiet and gentle. It does not have anything like the menacing presence of a raakshasa (man-eating monsters) to contend with, as in The Man-eater of Malgudi. Nor is there a whole community of people, which in its blind trust and faith helps in the transformation of a ragamuffin and rascal into a saint and martyr, as in The Guide. There is no run on a private bank by hundreds of panic-stricken depositors, as in The Financial Expert. Nor does a magnificent tiger stray into the streets of Malgudi, as in A Tiger for Malgudi, to throw its people into utter confusion to start with, and later into attainment of mystical illumination. Instead The Vendor tells us the domestic story of a father and son. An impulsive and drastic reduction of the price of sweets is the only sensational thing to happen in it. Unlike The Man-eater of Malgudi, its predecessor, which presents a richly peopled world almost Chaucerian in its variety, this novel focuses attention on a limited number of people: Jagan the protagonist, his son Mali, Mali’s companion Grace, and Jagan’s ubiquitous cousin who is not given a name. In addition to these chief characters, there are Jagan’s wife Ambika, his parents, Chinna Dorai the hair-blackener and sculptor, and a few others. If the number of characters is limited in this novel, it presents greater psychological subtlety and depth of feeling than many other novels of Narayan.

Read the rest of this article »