by Arthur D. Colman M. D.

Benjamin Britten, c. 1950s; photographer unknown; courtesy of operanews.com

Benjamin Britten is one of the great composers of the twentieth century. He is also one of those rare individuals who was able to live fully and creatively the life he fervently wished for as a child. Musical composition was his desired life; in the spirit of Puccini’s great aria from Tosca, “Vissi d’Arte,” his was a life in art, and art in life.

A child may be filled with desire to express objectively the music that is in his mind, and because music is so demanding an art form it may take years to master even the technical and aesthetic requirements. Finally, though, a composer will be judged on something more than his skill and the beauty of what is created. For Britten to become a great composer, which was his conscious desire, his music would need, in the words of Indian musicologist Anupam Mahajan, to be “a realization of the essence of existence beyond the routine life of man.” (Mahajan 1989, p. 13)

I believe that Britten achieved something of that essence in much of his music. Britten was a composer whose music communicated his deepest moral convictions, his fundamental truths in life. Because these were not consonant with the world around him, his music became the language of a prophet who lived, as prophets often do, on a fragile boundary between the Wilderness and the Ruler’s Court. The compelling beauty of his music made it possible for Britten to navigate this line and be heard by many people who preemptively disagreed with his message. His subjects, so relevant to his own and today’s world, were the subjects of many prophets before him: Violence, Injustice, Innocence Betrayed, the Scapegoat, and most of all, War.

Read the rest of this article »

by Ken Butigan

Cover of Berrett-Koehler edition; courtesy of the publisher

The Nonviolence Handbook: A Guide for Practical Action— a new volume by long-time peace and nonviolence scholar Michael Nagler published this month by Berrett-Koehler — offers the reader a crisp articulation of the dynamics, principles and contemporary application of Gandhian nonviolence that is both brief and clear. A scant 84 pages, including footnotes and an index, this publication really is a handbook in the classic sense: a short compendium of concise information about a particular subject, a type of reference work, a collection of instructions, and something “small enough to be held in the hand.” Nagler’s new book is, in this sense, a handy summary of the workings of nonviolent change and how it can transform our lives and our world.

In the interest of full disclosure, let me say from the outset that I was Nagler’s teaching assistant years ago and he, in turn, served on my degree committee in graduate school. I have always found his work a powerful contribution to nonviolent studies. I have used his publications in my teaching, including The Search for a Nonviolent Future, which I consider to be one of the best books ever written on the power of nonviolence. Even before meeting Nagler, though, his work influenced me strongly. As a neophyte activist in the 1980s I happened upon his America Without Violence, which opened up for a social change newbie a vision of nonviolence grounded in humanity’s potential. It helped strengthen my hope that enduring nonviolent transformation was possible.

Read the rest of this article »

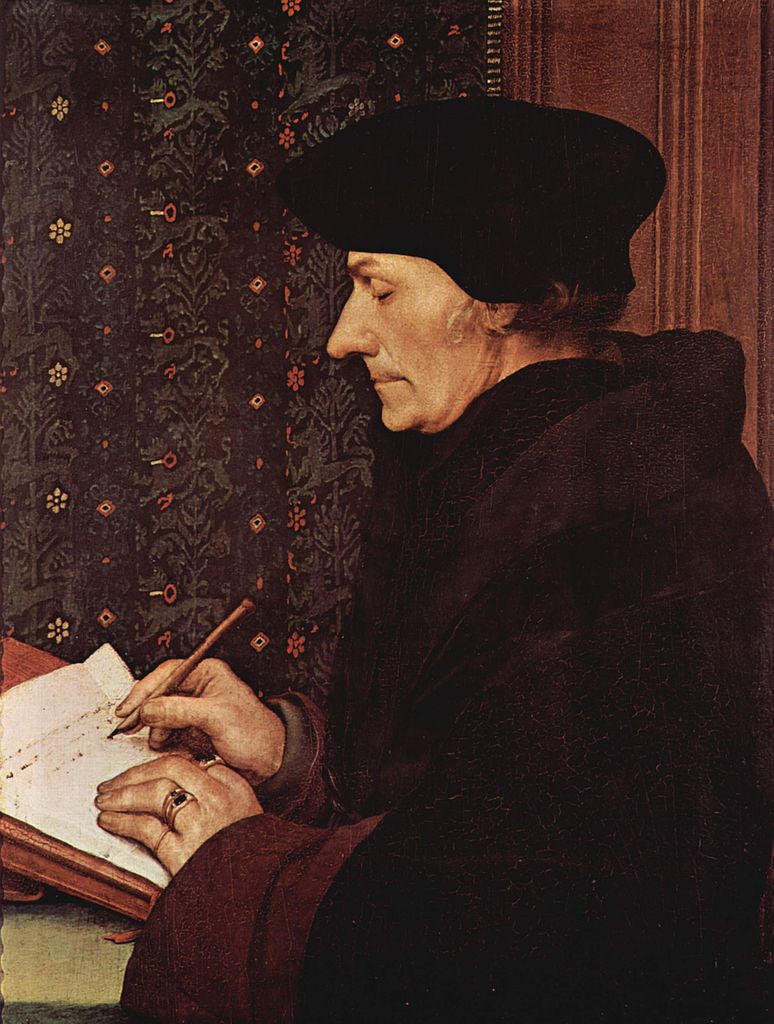

by Peter van den Dungen

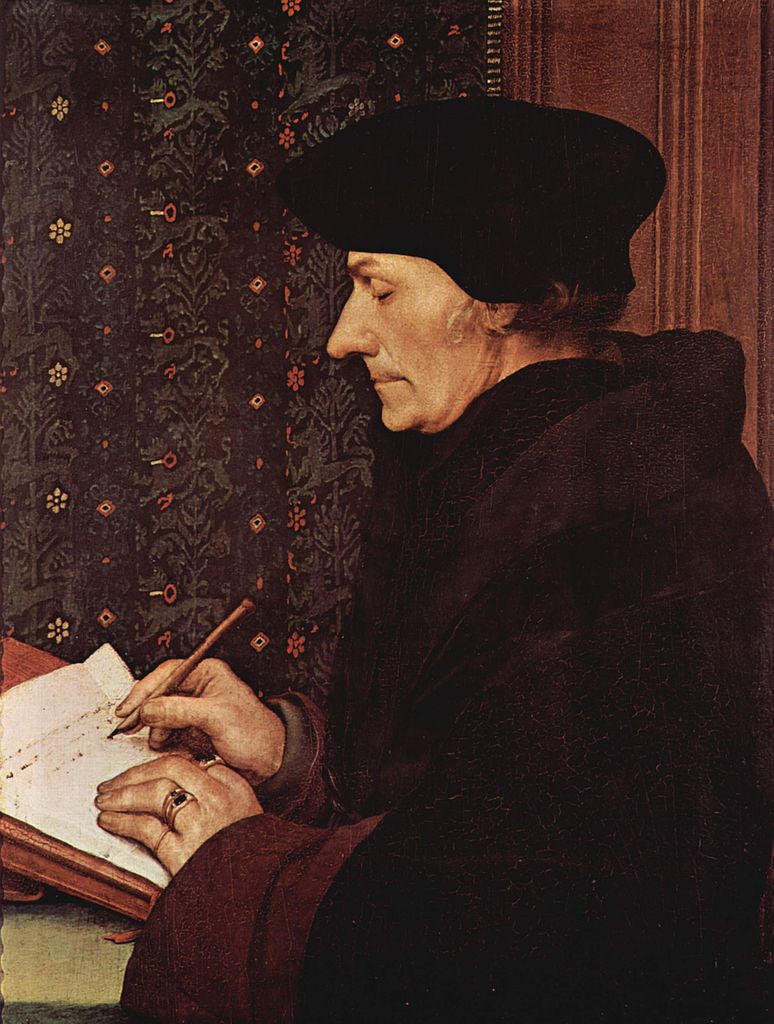

Erasmus, by Hans Holbein the Younger; courtesy of the Louvre

More than a century before Grotius wrote his famous work on international law, his countryman Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam laid the foundations for the modern critique of war. In several writings, especially those published in the period 1515-1517, the ‘prince of humanists’ brilliantly and devastatingly condemned war not only on Christian but also on secular/rational grounds. His graphic depiction of the miseries of war, together with his impassioned plea for its avoidance, remains unparalleled. Erasmus argued as a moralist and educator rather than as a political theorist or statesman. If any single individual in the modern world can be credited with ‘the invention of peace’, the honour belongs to Erasmus rather than Kant whose essay on perpetual peace was published nearly three centuries later.

Read the rest of this article »

by Peter van den Dungen

Logo, Peace Museum, Bradford, UK; courtesy of www.peacemuseum.org.uk

In his essay Perpetual Peace (1795), Kant made it clear that we are called upon to make strenuous efforts for building a world without war. Neither the world in which we find ourselves, nor the human beings that are born into it, are inherently peaceful. However, Kant believed that rational and moral progress was possible, on the part of individuals as well as societies, and that – in the distant future – a global, cosmopolitan world order of peace and justice could emerge. In an earlier essay, Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View (1784), he wrote that future generations ‘will naturally value the history of earlier times … only from the point of view of what interests them, i.e., in answer to the question of what the various nations and governments have contributed to the goal of world citizenship, and what they have done to damage it.’ In the eighth thesis of this essay he asserted that the Idea (for a universal history from a cosmopolitan point of view) ‘can help, though only from afar, to bring the millennium to pass.’ Almost two hundred years later, Kenneth E. Boulding, one of the pioneers of modern peace research, argued likewise the need for ‘universal history’, a new kind of history writing, teaching, and learning that should replace the traditional, narrow, nationalist approach – a main ingredient in the complex of factors leading to war. The narrow geographical perspective is only one aspect of traditional history which is also characterised by gender, race, and religious bias. New kinds of history, more inclusive and objective, emerged only in the last century as a consequence of the emancipation of increasing numbers and categories of people (women, black, gay, disabled). It is also in this context, and especially against the background of two world wars, the development and use of atomic weapons, the Cold War, and the protest movements that have sprung up against them, that a specialised field of history has emerged: peace history.

Read the rest of this article »

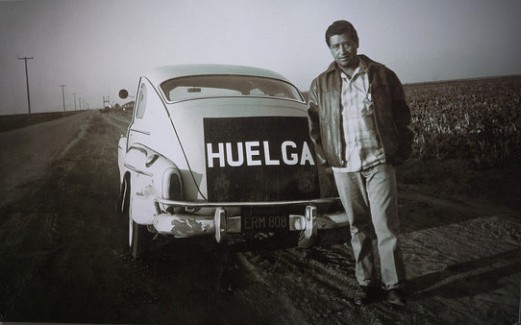

by José Antonio Orosco

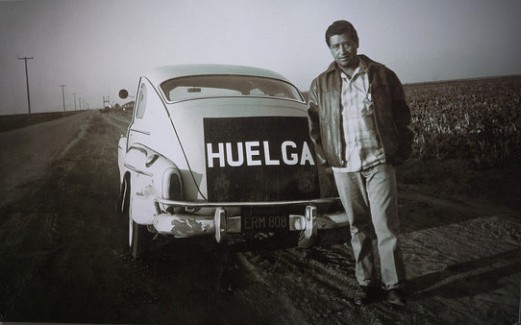

Cesar Chavez on strike; courtesy Flickr/Jay Galvin

The recent release of Diego Luna’s new film, Cesar Chavez: An American Hero (starring Michael Peña and John Malcovitch), and the documentary Cesar’s Last Fast directed by Richard Ray Perez (premiered at the Sundance Film Festival), give us new opportunities to reflect on the lessons of Chavez’s life and activism. While his charismatic leadership turned him into a powerful force for justice, an unyielding grip on his position of authority ultimately weakened the organization he worked to build.

The title An American Hero is appropriate. Chavez’s life unfolded like a classic American success story. His family lost everything during the Great Depression, and Chavez managed to get only an eighth grade education in between stints working in the fields of California. Yet he went on to found a powerful organization that forever changed American history by giving voice to some of the most disadvantaged members of our society. There are valuable lessons to take from his determination, as well as his stubbornness.

Read the rest of this article »

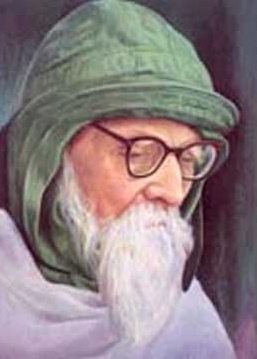

by Mark Shepard

Vinoba Bhave; photographer unknown; courtesy of bharatmatamandir.in

Once India gained its independence, that nation’s leaders did not take long to abandon Mahatma Gandhi’s principles. Nonviolence gave way to the use of India’s armed forces. Perhaps even worse, the new leaders discarded Gandhi’s vision of a decentralized society, a society based on autonomous, self-reliant villages. These leaders spurred a rush toward a strong central government and a Western-style industrial economy. But not all abandoned Gandhi’s vision. Many of his “constructive workers”, development experts and community organizers working in a host of agencies set up by Gandhi himself, resolved to continue his mission of transforming Indian society. And leading them was a disciple of Gandhi previously little known to the Indian public, yet eventually regarded as Gandhi’s “spiritual successor”, Vinoba Bhave, a saintly, reserved, austere man most called simply Vinoba. How did he assume this status?

In 1916, at the age of 20, Vinoba was in the holy city of Benares trying to come to a decision about his life. Should he go to the Himalayas and become a religious hermit? Or should he go to West Bengal and join the guerillas fighting the British? Then Vinoba came across a newspaper account of a speech by Gandhi. He was thrilled, and soon after joined Gandhi in his ashram. Gandhi’s ashrams were not only religious communities, but also centers of political and social action. As Vinoba later said, he found in Gandhi the peace of the Himalayas united with the revolutionary fervor of Bengal.

Read the rest of this article »

by Narayan Desai

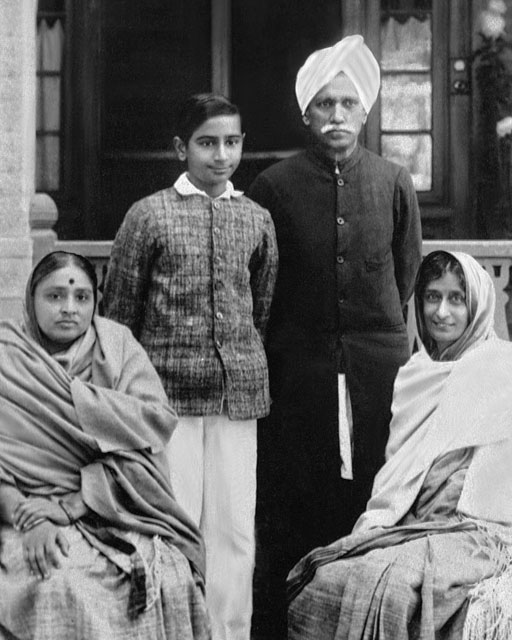

Editor’s Preface: Narayan Desai (b. 1924) is the son of Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s chief secretary until 1942. He is the founder of the nonviolence training center, the Institute for Total Revolution, and the author of a four volume biography of Gandhi among other works. He has been awarded both the Jamnalal Bajaj Award and the UNESCO Madanjeet Singh Prize for his work in nonviolence and pacifism. JG

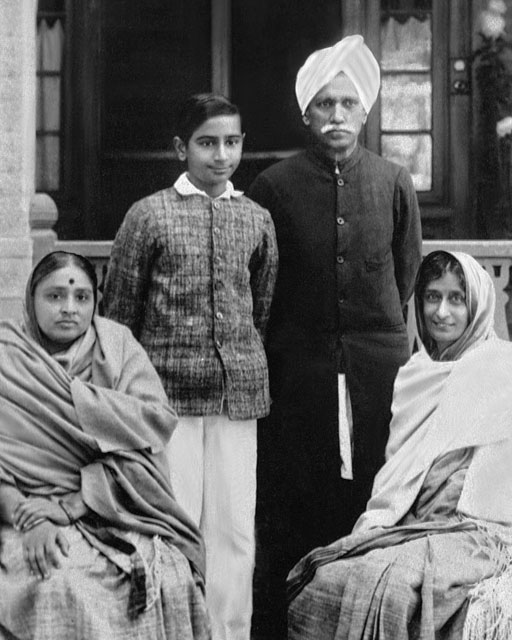

Young Narayan Desai with parents; photo courtesy Narayan Desai

The Satyagraha Ashram of Mahatma Gandhi stood on the bank of the broad Sabarmati River, across from the city of Ahmedabad. “This is a good spot for my ashram,” Bapu used to say. All of us in the ashram called him Bapu, or Father. He added, “On one side is the cremation ground. On the other is the prison. The people in my ashram should have no fear of death, nor should they be strangers to imprisonment.” Indeed, my earliest memories of Bapu are intertwined with those of Sabarmati Prison. Bapu would go for a walk each morning and evening. He would put his hands on the shoulders of those to either side. These companions would be his “walking sticks.” We children were always given first choice for this job. Whether his human walking sticks were really any help to him, perhaps only Bapu could say. But as for us, being chosen always made us swell with pride. In fact, in our eagerness to be chosen Bapu’s “sticks”, we would sometimes clash.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bashar Humeid

Editor’s Preface: The Syrian philosopher and theologian Jawdat Said (b. 1931) is one of the most important theorists of Islamic nonviolence. There is an English language website devoted to his life and work, and also posts an English translation of his Nonviolence: the Basis of Settling Disputes in Islam that you may download for free. JG

Al Jazeera screen capture; courtesy of jawdatsaid.net/en/

Jawdat Said’s book The Doctrine of the First Son of Adam: The Problem of Violence in the Islamic World (1966) was the first publication in the modern Islamic movement to present a concept of nonviolence. Now in its fifth edition, the book is still in print. Said was born in Syria in 1931, but moved to Egypt at a young age to study Arabic language at Azhar University in Cairo. While there, he took an active part in the cultural life of Egypt, and was also closely connected to the Islamic movement of that period. Even back then, Said was already warning about the negative effects of the violence being carried out by the Islamic movement in Egypt. He wrote his book as a direct response to the writings of Sayyid Qutb, who died in 1966 and is considered the father of militant Islam. (1)

Other intellectuals of the Islamic world also disagreed with Qutb, including Hasan al-Hudaybi, the leader of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. (2) In the early 1980s, the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria began – in spite of Said’s warnings – to rebel against the government of Hafez al-Assad. (3) However, the revolt was put down with much bloodshed, and ended in 1982 with a massacre in the city of Hama. Following this defeat, the Syrian movement began seriously entertaining the idea of demilitarization, and the writings of Jawdat Said became increasingly influential in Islamic activist circles.

Read the rest of this article »

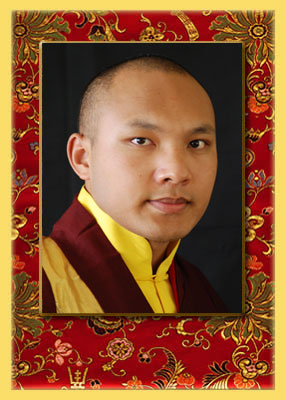

by Ogyen Thinley Dorje, His Holiness the 17th Karmapa

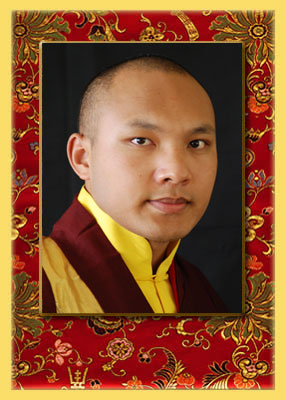

Ogyen Thinley Dorje; photographer unknown; courtesy of Karma Triyana Dharmachakra

Ever since the human race first appeared on this earth, we have used this earth heavily. It is said that 99% of our resources come from the natural environment. We are using the earth up. The earth has given us immeasurable benefit, but what have we done for the earth in return? We always ask for something from the earth, but never give her anything back. We never have loving or protective thoughts for the earth. Whenever trees or anything else emerge from the ground, we cut them down. If there is a bit of level earth, we fight over it. To this day we perpetuate a continuous cycle of war and conflict over it. In fact, we have not done much of anything for the earth. Now the time has come when the earth is scowling at us; the time has come when the earth is giving up on us. The earth is about to treat us badly and give up on us. If she gives up on us, where can we live? There is talk of going to other planets that could support life, but only a few rich people could go. What would happen to all of us sentient beings who could not go?

What should we do now that the situation has become so critical? The sentient beings living on the earth and the elements of the natural world need to join their hands together—the earth must not give up on sentient beings, and sentient beings must not give up on the earth. Each needs to grasp the other’s hand. So doesn’t the Monlam logo look like two hands clasping each other?

Dream Flag design; courtesy of khoryug.com

Its shape is similar to the design of the Sixteenth Gyalwang Karmapa’s Dream Flag, of peace and serenity, which is used regularly among the Karma Kamtsang tradition. If I were to make up everything myself, I doubt it would have any blessings, but using the previous Karmapa’s design as a model probably gives this logo blessings. This is a symbol of our Kagyu Monlam that we hold for the benefit of the entire world. We will not give up on the earth! May there be peace on earth! May the earth be sustained for many thousands of years! These are the prayers we make at the Kagyu Monlam, which is why this symbol is the logo of the Monlam. (1) I think it also might become a symbol of people having affection for the earth and wanting to protect it.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bharat Mansata

Bhaskar Save on 92nd birthday; photograph by the author

Bhaskar Save, acclaimed “the Gandhi of Natural Farming”, turned 92 on 27 January 2014, having inspired and mentored three generations of organic farmers. Masanobu Fukuoka, the legendary Japanese natural farmer, visited Save’s farm in 1996, and described it as “the best in the world”, ahead of his own farm. In 2010, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) honoured Save with the “One World Award for Lifetime Achievement”.

Indeed, Save’s farm is a veritable food forest; a net supplier of water, energy and fertility to the local eco-system, instead of a net consumer. His way of farming and his teachings are rooted in a deep understanding of the symbiotic relationships in nature, which he is ever happy to explain in simple, down-to-earth idioms to anyone interested. Save’s 14 acre orchard-farm Kalpavruksha is located on the Coastal Highway near village Dehri, District Valsad, in southernmost coastal Gujarat, a few km north of the Maharashtra-Gujarat border. The nearest railway station is Umergam on the Mumbai-Ahmedabad route.

Read the rest of this article »