Gandhi in the Postmodern Age

by Sanford Krolick and Betty Cannon

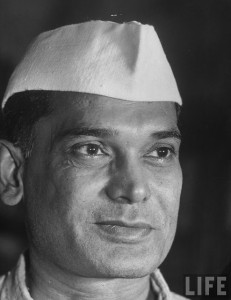

Poster art; courtesy whataboutgandhi.com

The theory of nonviolence as an offspring of democracy is still in its infancy. Mohandas Gandhi, the master of this philosophy and its methods, was educated in Britain as a lawyer and learned well the principles of democracy. Throughout his years in South Africa and in the campaign for Indian independence, his efforts in dealing with conflict were consistent with the basic beliefs of democracy. While others fought revolutions promising that victory would bring democracy, Gandhi brought about revolutions using democratic principles and techniques; his victories were signified by the acceptance of democracy. Gandhi never tired of talking about the means and ends, claiming that the means used in settling the dispute between the Indian people and the British Government would determine the type of government India would evolve. He was fond of saying that if the right means are used, the ends will take care of themselves.

Gandhi called his philosophy satyagraha. In the United States it has been called nonviolence, direct action, and civil disobedience. These terms are inadequate because they only denote specific techniques Gandhi used. However, for the purposes of this discussion, we will use nonviolence to designate the philosophy and resisters to designate those who adopt this philosophy and carry out its methods.