My Magical School: Gandhi’s Sevagram Ashram Experiment in Education

by Dr. Abhay Bang

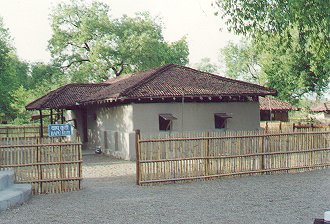

Sevagram Ashram, c. 1960s; courtesy mkgandhi.org

As a child growing up in the 1960s I went to an amazing school. Today, I feel helpless and sad because I’m unable to offer such an education to my son, Anand. “Our childhood was so different. Things have changed beyond recognition,” old timers often moan and groan about the past. Still, my heart is heavy. You may ask what was so different about my school?

From grades four to nine I studied in a school which followed Gandhi’s Basic Education tenets (Nai Taleem), located at Sevagram ashram in Wardha, founded by Gandhi in the 1930s. Education should not be confined within the four walls of the classroom mugging up boring subjects away from Mother Nature. Gandhiji’s Nai Taleem strongly believed that children learnt best by doing socially useful work in the lap of nature. This is how children’s minds would develop and they would imbibe a variety of useful skills. To implement such a system of education, the great poet and Nobel Prize winner, Rabindranath Tagore, at the behest of Gandhiji sent two brilliant teachers to Sevagram. Mr. Aryanakam came all the way from Sri Lanka and Mrs. Asha Devi from Bengal. This duo combined Gandhi’s educational methodology with Tagore’s love for nature and the arts. My parents, followers and friends of Gandhi, were involved with this educational experiment right from the start. The school tried out many novel experiments in education. Here, I will attempt to recall some of these.