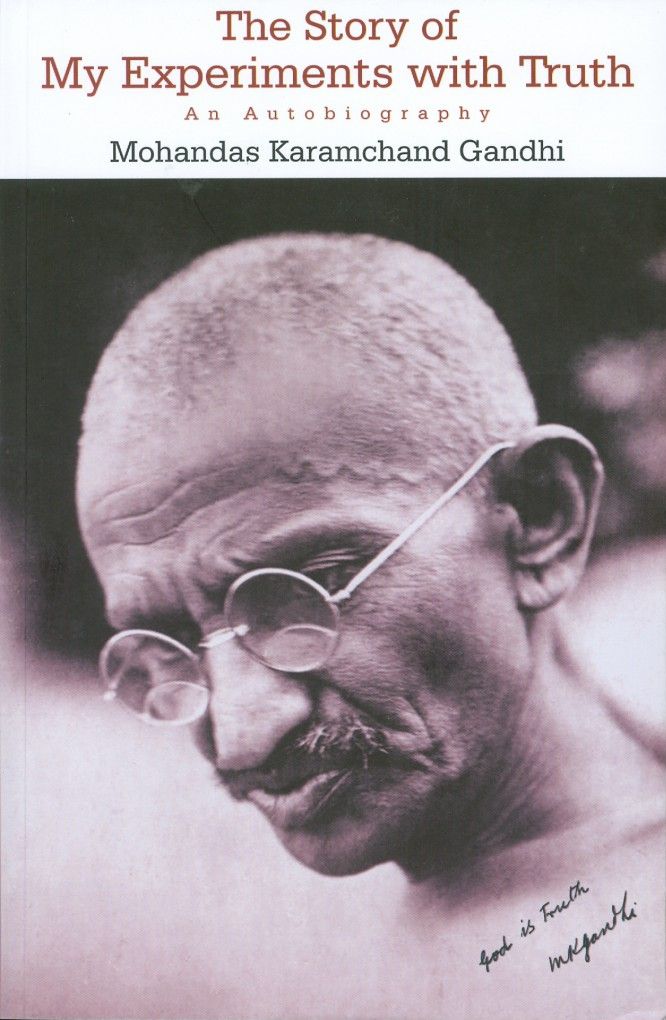

by Vinay Lal

Indian folk art representation of Gandhi’s assassination; courtesy Vinay Lal collection

Uniquely among the major public figures of the modern world, Mohandas Gandhi attracted an extraordinarily wide and diverse following and, perhaps oddly for someone who is customarily thought of in terms of veneration, an equally if not more diverse array of often relentlessly hostile critics. (1) The first part of this story is better known than the latter part of the narrative around which this paper is framed, (2) though much remains to be understood about the manner in which Gandhi, notwithstanding his rather strident views on modernity, industrial civilisation, materialism, sexual relations, indeed on everything that is ordinarily encompassed under the rubric of social and political life, drew to himself people from very different walks of life.

Among his most intimate disciples, who, it is no exaggeration to say, surrendered their life to the Mahatma, one thinks of the daughter of an English admiral, raised on the music of Beethoven in the lap of luxury and immense privilege; a Tamil Christian, trained as an accountant and economist, who was among the first Indians to earn a degree in business administration; a Gujarati villager, son of a schoolteacher, who was embraced by Gandhi when they first met in 1917 as something like a long-lost son; and an Anglican clergyman, arriving in India from Britain on what was destined to become a one-way ticket, who came to the realization that Gandhi was a better Christian than many who call themselves Christians. (3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

Poster art, courtesy indorigins.com

It may seem surprising that no significant study has as yet compared the lives, works, and ideas of Mahatma Gandhi and Michel Foucault. (1) Foucault (1926–1984), a French political and social theorist, and Gandhi (1869–1948), the saintly Indian political leader, initially appear to have very little in common, and indeed strike us as intellectual opposites. Gandhi was a deeply religious man who committed at least an hour each day to prayer and meditation; Foucault was a committed atheist who resented his bourgeois Catholic upbringing and blamed religion for much of the malaise afflicting modern man. Gandhi believed that human society and relationships could be transformed through individual hard work, selfless kindness, and love; Foucault was concerned to draw attention to hidden motivations of power in all social relations, and emphasized the often powerless positions of individuals vis-à-vis larger institutional structures. Gandhi fasted regularly, never took food after sunset, and upheld a vow of strict brahmacharya (celibacy) for the last 38 years of his marriage; Foucault maintained a fascination with intense sensory experiences, ever seeking stronger sensations through drugs and sex, and explored his interest in sexual pleasure in his final and definitive works, the three volume History of Sexuality. The reader could be forgiven for thinking that two more different men could hardly be found.

Read the rest of this article »

by M. P. Mathai

Tree hugging photograph; courtesy spiritualecology.org

The ecological crisis we confront today has been analysed from various angles, and scientific data on the state of our environment are readily available. Humanity has come out of its foolish self-complacency and has awakened to the realisation that over-exploitation of nature has led to a very severe degradation and devastation of our environment. Scholars, through joint studies and research projects, have brought out the direct connection between consumption and environmental degradation. For example, professor of planning and development, Inge Ropke, has raised pertinent questions in his paper, “The Dynamics of the Willingness to Consume”: Why are productivity increases largely transformed into income increases instead of more leisure? Why is such a large part of these income increases used for consumption of goods and services with a relatively high materials-intensity instead of less material-intensive alternatives?

Read the rest of this article »

by Asha Devi Aryanayakam

Editor’s Preface: This article is taken from The War Resister, issue 92, Third Quarter 1961. We have posted a number of other articles on Shanti Sena, which may be accessed via our search function. Notes about the author, references, and acknowledgments are found at the end. JG

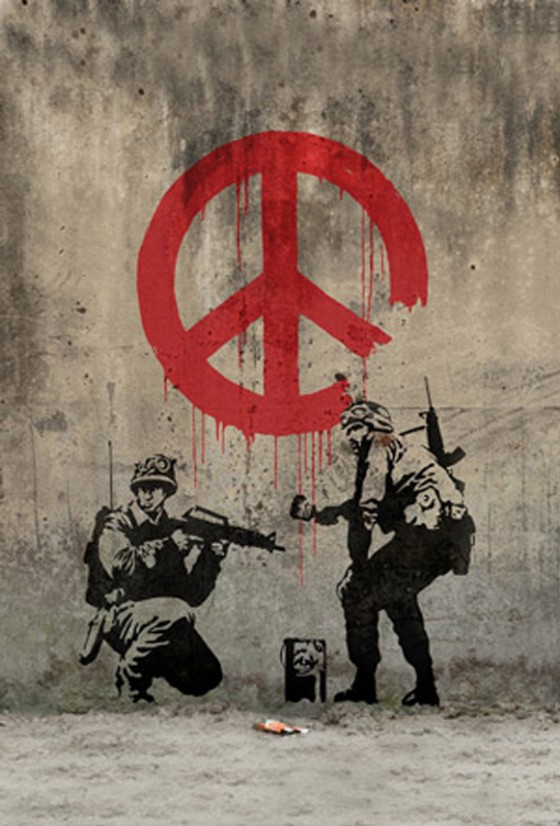

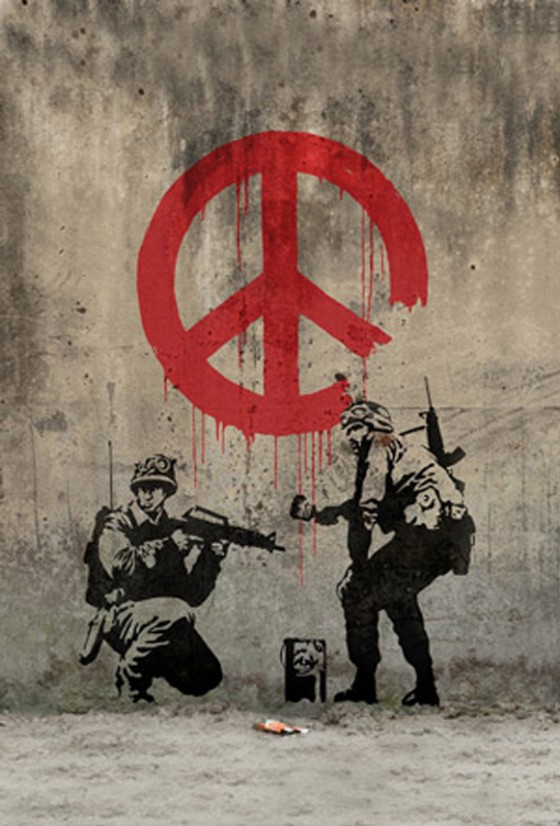

“Soldiers Painting Peace”; mural by Banksy; courtesy stencilrevolution.com

The conception of a Peace Brigade or a Peace Army was first placed before the Indian people by Gandhi in 1938. He was then engaged in the great experiment of reconstructing Indian national life through nonviolence. The movement for political independence was only a part of the story. The monster of communal tension had just begun to rear its ugly head and the Peace Army was Gandhi’s answer to the problem. With his characteristic straightforwardness, he placed his proposal in down-to-earth practical terms without any philosophical introduction.

As he wrote, ‘Some time ago I suggested the formation of a Peace Brigade (Shanti Sena), whose members would risk their lives in dealing with riots, especially communal. The idea was that this brigade should substitute for the police and even the military. This sounds ambitious. The achievement may prove impossible.’

Gandhi then suggested qualifications for the volunteers, which are mentioned by Donald Groom in his contribution to this issue of the War Resister [posted below under this date]. As Gandhi wrote, ‘Let no one understand from the foregoing that a nonviolent army is open only to those who strictly enforce in their lives all the implications of nonviolence. It is open to all those who accept the implications and make an ever increasing endeavour to observe them. There never will be an army of perfectly nonviolent people. It will be formed of those who will honestly endeavour to observe nonviolence.’ (Harijan, 21.7.1940.)

Read the rest of this article »

by Donald G. Groom

Editor’s Preface: This article is taken from The War Resister, issue 92, Third Quarter 1961. We have posted a number of other articles on Shanti Sena, which may be accessed via our search function. Notes about the author, references, and acknowledgments are found at the end. JG

“Shanti/Peace” in Sanskrit; courtesy palmstone.com

In my view there are two main aspects of the World Peace Brigade, that of individual and group action carrying out service or direct peace action; the other the supporting action of thousands and millions who have heartfelt sympathy with its purposes. All will have faith in the revolutionary power of love and compassion in all spheres of human activity and in the innate goodness of man, even though the upholding of this faith may involve suffering and death. But those people who are chosen for direct involvement in the problems of human suffering, tension, fear and all forms of violence would have to function at a different level and demonstrate the power of nonviolence for peacemaking which could only come through a high quality of life and discipline. What is expected therefore from such volunteers?

Read the rest of this article »

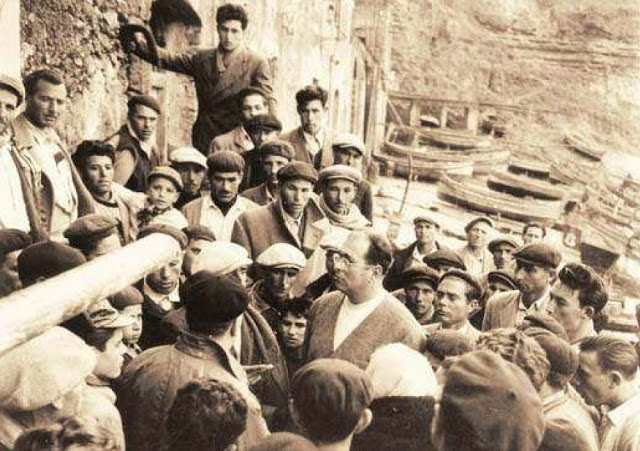

by Prof. Giovanni Pioli

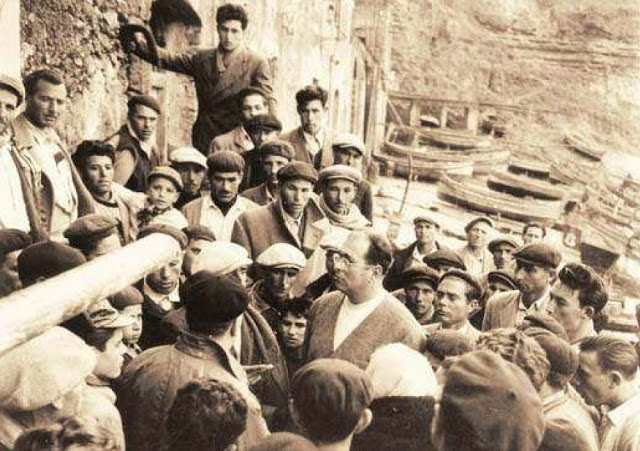

Dolci organzing the fishermen of Trappeto, 1952; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Editor’s Preface: This article continues our series of historically important articles from the War Resisters’ International archive, our goal to trace the influence of Gandhian nonviolence on the early pacifist movements. This is from The War Resister, issue 71, Second Quarter 1956. We have previously published articles by or about Dolci, one of the great exponents of Gandhi’s constructive program. These may be accessed via our search box. Please consult the notes at the end for further information. JG

Pamphlets, bulletins and books have now been written by Danilo Dolci and the valiant men and women who join him for a time to share his experience, his poverty, his distress and his hard labour for the uplift of those submerged, demoralised ‘criminal’ masses who struggle — even beyond legal limits — for the bare necessities of life. Italian social workers, pacifists, and humanitarians respect this literature, dealing with conditions in Trappeto and Partinico, situated in the Province of Palermo, Sicily — infamous as a centre of Sicilian banditry and the mafia.

Read the rest of this article »

by Dr. Susan S. Bean

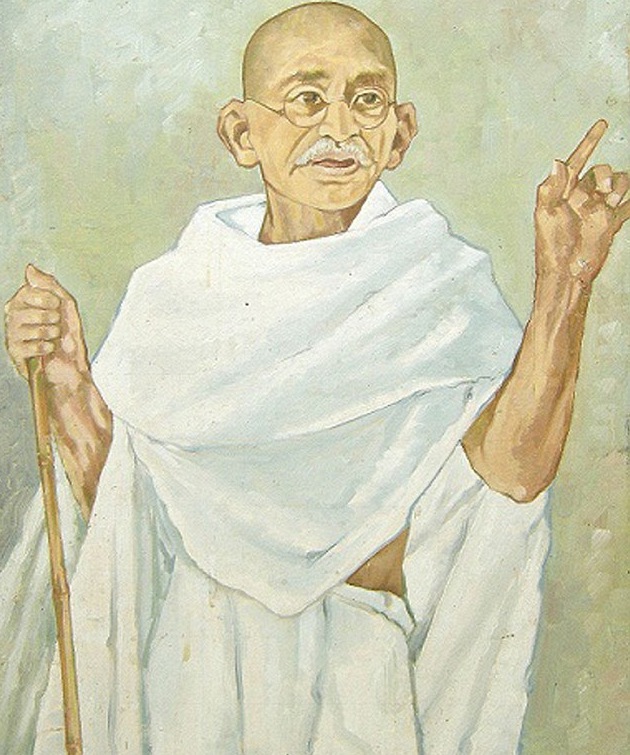

Painting of Gandhi, c. 1945, by J. L. Bhandari; courtesy dailymail.co.uk

Prologue: The story of khadi (homespun) and its creator Mohandas Gandhi is well known in India and around the world. In his political campaign for Indian self-determination (swaraj), Gandhi famously promoted the practices of making thread through spinning by hand, and wearing simple khadi garments – not only as key symbols of national identity, but also as a central statement of resistance to the colonial regime. As writer, producer and director, Gandhi instigated a national drama centred on the roles of spinner and khadi-wearer. Made from hand-spun yarn, his khadi would emerge from India’s handlooms not just to costume the nation but also to change the essential character of its people, altering colonial subjects into ‘citizens’. Seen as theatre, the narrative of khadi reveals how Gandhi transformed this cloth into much more than a mere textile, and how khadi exerted transformative and long lasting effects in India’s national movement. The drama of khadi illuminates the potency and tenacity inherent in this humble homespun cloth; already having proved itself within the framework of the freedom struggle, the story of khadi still resonates more than sixty years after India gained Independence. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by H. Ahmed

Editor’s Preface: This article is from The War Resister, issue 70, First Quarter 1956, and continues our series of essays on nonviolence in Islam. Please consult our Islam category for further articles. Reference and acknowledgments are at the end. JG

“Islam is Peace”; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

In the limited space at my disposal, I will concern myself with the fundamental principles of pacifism in Islam, as taught by the great Prophet of Arabia. As in the case of almost all the other religions, Islam has also been betrayed by its followers, so much so that the other day I came across a rather blunt remark that there is no place for nonviolence in Islam and that Islam does not advocate the establishment of world peace. And it is very often that we come across such remarks.

There is a bar to all knowledge, and that is contempt prior to investigation. Any scholar who studies the original Islam without preconceived ideas will realise that Islam is also a religion of peace and that it also advocates pacifism. It aims at the welfare and prosperity of every human being without the difference of caste, creed, colour or nationality. The teachings of Islam lead one to the golden rule of “Live and let live for mutual forbearance and tolerance”. The Prophet of Arabia declared, “Faith is restraint against all violence”. Further exhorting his followers to non-violence, he said, “Let no Muslim commit violence!” Can there be a clearer injunction than this?

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

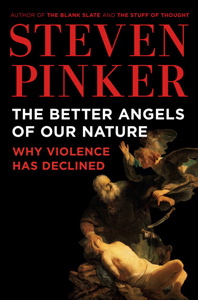

Cover art courtesy stevenpinker.com

Amongst the scores of letters he attended to every day, Mahatma Gandhi responded to one V.N.S. Chary, on April 9, 1926. Chary’s original letter does not survive, but we may reconstruct from the Mahatma’s response that he raised a particular existential question that has long troubled many practitioners of nonviolence: Is overcoming violence really possible? Is violence not simply an ineluctable feature of embodied existence and human nature? Questions in this spirit have a long history, having been explored by thinkers such as Heraclitus, Freud, Nietzsche, and others, who have often emphasized the essential duality of worldly existence – of the mutual necessity of opposites – for good to exist, so must evil; to know peace, perhaps we must know violence.

In his letter, Mr. Chary appears to have cited examples from the animal world: Hawks eat snakes; snakes eat lizards; lizards eat cockroaches, who themselves eat ants. This violence is simply natural, and it occurs perhaps for a greater good. If beings did not eat other beings, life on earth would not be possible. Beyond Chary’s points, we might also reflect that even our own human bodies are unavoidably violent; besides periodically crushing or inhaling insects unawares, our own white blood cells are constantly exterminating malignant bacteria; if they failed to kill these bacteria, we would die. Is violence not necessary for life, and should we not see it as unreasonable, or indeed impossible, to hope for a renunciation of violence?

Read the rest of this article »

by H. Runham Brown

Editor’s Preface: H. Runham Brown was a British anarchist and secretary of War Resisters’ International. He was appointed in 1931, soon after being released from prison, having served two years for conscientious objection. He authored books about peace and the Spanish civil war, and Hitler’s rise. This article is taken from The War Resister: Quarterly News Sheet of the War Resisters’ International, issue XXXI, Summer 1932. Please also see the archive reference information and acknowledgments at the end. JG

Few people in the West can understand why a man should go on a hunger strike. It appears to them that he is only hurting himself and they would rather hurt somebody else. We do not here ask that so strange an action should be understood, but that a fact should be taken notice of. From time to time a man in prison refuses to take food until his objective has been attained. He is forcing the issue. Such action may be wise or foolish; it depends on the man.

Read the rest of this article »