Gandhi’s Vision of Nonviolence, Holding Firm to Truth: The Street Spirit Interview with Jim Douglass, Part 4

Anti Iraq War protest, Washington, D.C., Sept. 15, 2007, courtesy Wikipedia.org

“We chose to be in the sights of the weapons of our own troops. For a few days, we were just as vulnerable as the Iraqi people. Explosions were occurring all over the city from missile attacks by our fleet in the Gulf.” Jim Douglass

Street Spirit: Gandhi referred to campaigns of nonviolent resistance as “satyagraha” — holding firmly to truth. What are the essential steps in building satyagraha campaigns, both in Gandhi’s era and in our time?

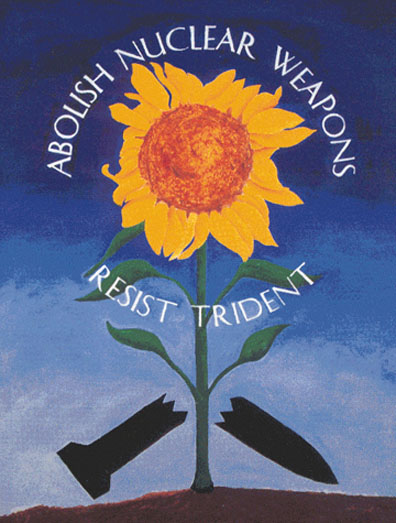

Jim Douglass: The most basic thing is the commitment of the people who seek to engage in such a campaign. There would have never been satyagraha campaigns in Gandhi’s life if he hadn’t created communities out of which they could be waged. The ashrams in South Africa and later in India were the bases of his work. And even though the number of people living in community and taking vows of nonviolence was small, those people were totally freed to work together and to respond to the specific evils they focused on. As Gandhi always taught, you can’t take on everything in the world, so you focus by identifying a social evil, as for example we did in the Trident campaign.