by William J. Jackson

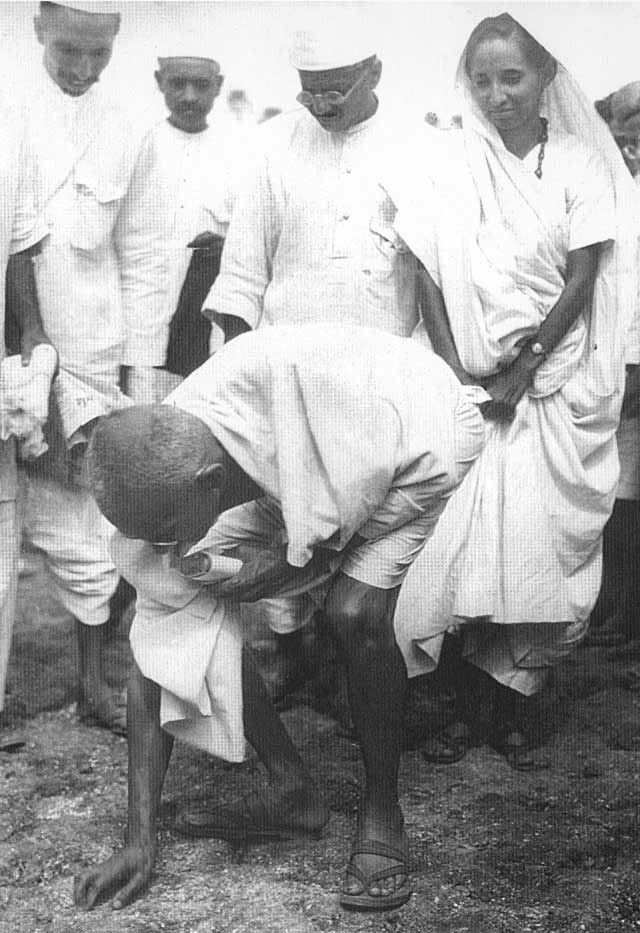

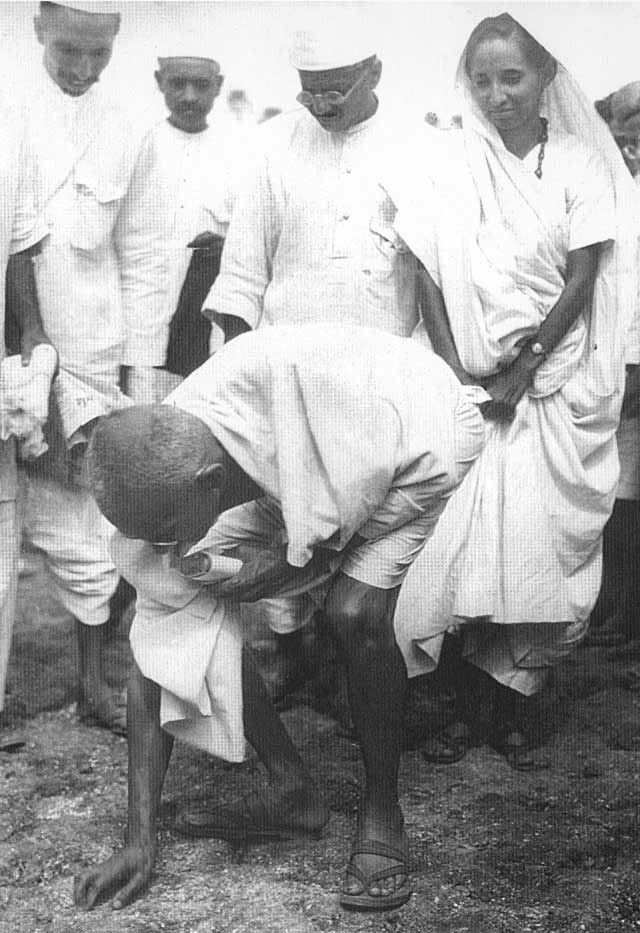

Gandhi gathers salt and breaks law; courtesy Wikipedia.com

Why Symbolism of Salt to Understand a Trouble Dissolver?

Alchemy is a kind of learning, a repository of old wisdom. It includes observations about elements, experiments with materials and aspects of the universe, as well as studies about processes and psyches. The imagination of curious souls and observers of life, active over the centuries, has experimented and found meanings in chemical and psychic interactions and transformations.

Despite modern science’s new technologies and ways of learning about the universe at various levels—micro, macro, meso—there are still valuable lessons to be learned from the ideas gathered under the term “alchemy” over the centuries. Shakespeare and other great poets are still interesting 500 years later—his grasp of human nature, his use of metaphorical language, and his observations on experience are still valuable, and this is true also for the metaphors found in alchemy.

James Hillman’s Alchemical Psychology is a brilliant contribution to understanding the richness of alchemy. In this book he garners and examines some valuable insights from the explorations of alchemy, and relates them to the processes of the human psyche. Many of the ideas in this paper are derived from Hillman’s inspiring work. I quote some points directly, others I paraphrase and elaborate on, extending them with my own examples and explicating and exploring their implications. Relating these ideas to Gandhi’s work is my idea, not Hillman’s. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

Logo Sri Lanka sarvodaya; courtesy lightmillennium.org

In March 1974, following a student demonstration in Patna against the Bihar Government and Assembly that resulted in widespread arson and looting and several deaths, Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) the leader of the Socialist Party and former Gandhi supporter, accepted an invitation from the student leaders to give guidance and direction to their movement. As he was to declare in a speech to these students, ‘After 27 years of freedom, people of this country are wracked by hunger, rising prices, corruption… oppressed by every kind of injustice… it is a Total Revolution and we want nothing less!’

His immediate purpose was to ensure that the developing agitation would be peaceful and nonviolent but, in accepting the invitation, he set in motion a train of events which included not merely splitting the Sarvodaya movement of which he was the most prominent leader after Vinoba Bhave but also, and more importantly, polarising all the major political parties and forces in India. Fifteen months later, this polarisation led to a head-on confrontation between the Opposition parties and the Central Congress Government (supported by the Communist Party of India), the outcome of which was the declaration of a state of emergency on 26th June 1975.

Read the rest of this article »

by Beverly Woodward

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished 1972 essay by Beverly Woodward is the latest in our series of discoveries from research that we are conducting in the IISG, Amsterdam. Please see the notes at the end for further details, references, acknowledgments, biographical information, and a link to the pdf file of the original. JG

The existing state of international disorder is often referred to as a state of global anarchy. The time honored human remedy for such a state of affairs is the establishment of the rule of law. Thus the remedy for the existing situation is often held to be the creation of more and better international law along with the creation of the institutions customarily associated with the presence of law, i.e., institutions for making, interpreting, and enforcing law. But there are many who are not enthused by the proposal. They include those national elites who speak piously of “law and order” at home, but are definitely less reverent when it becomes a question of forms of law that might be less supportive of their (self-defined) “interests” than the legal structures that they are so anxious to see upheld. They include the anarchists who insist that the current perversions in human behavior are not due to too little law, but to too much law, pointing out, for example, that it is governments that have authorized the great majority of the more brutal and massively destructive acts witnessed in this century. And they include many “ordinary people” who are neither opposed to law in general nor especially privileged by the given arrangements, but who are apprehensive of law formulated at such a great distance from its potential points of application. Even to those not inclined to rail against government wherever it occurs, “world government” or anything similar may seem a rather frightening remedy for what ails us.

Read the rest of this article »

by Devi Prasad

Schoolchildren dressing as Gandhi to commemorate his 146th birthday; courtesy newindianexpress.com

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished essay by Devi Prasad is another in our series from the IISG archive, Amsterdam. It is well to bear in mind that Prasad lived as a child at Tagore’s school, discussed in the article, and that he was later asked by Gandhi to teach in one of his ashrams. His knowledge of Gandhi’s education system, therefore, was uniquely first-hand. Please consult the notes at the end for archival reference, acknowledgments, and biographical information. JG

At the centre of Gandhi’s many concerns about social and political issues, there are two things that remained consistently predominant throughout his life. Firstly, a revolt against the education system that was given to, nay, imposed upon India by the colonial rule; and secondly, a powerful urge to find an appropriate approach and method of imparting education to all the children and adults of the country.

Read the rest of this article »

by Tristan K. Husby

Dustwrapper art courtesy Brazos Press; bakerpublishinggroup.com

A friend of mine who is an organizer and nonviolence trainer has a favorite exercise called “10-10,” which she uses when introducing nonviolence to new activists. She divides the students into groups and tells them to write down, as quickly as possible, 10 wars. Afterwards, they review all of the different wars that people have recalled. While there are a number of wars that are repeated, often each group has come up with some war that other groups have not thought of at all. When I first participated in this exercise, I was excited to contribute the rather obscure Corinthian War. Then she asks the groups to write down 10 nonviolent struggles. This task always takes longer and some groups run out of time before they can complete the task.

The point of the “10-10” exercise is to drive home how our society pays close attention to wars and violent conflicts: We devote countless news articles, books and classes to retelling the history of these violent events. It is not surprising then that for the past 40 years much of the literature on nonviolence has been historical. Scholars and writers have uncovered, recorded and preserved examples of nonviolent struggles from across the world and from many different time periods so that activists can know for themselves and convince others of the efficacy of people power. Other writers, such as the philosopher Todd May and the theologian Ronald Sider, have adopted this idea of historical research being necessary to argue about and promote nonviolence in new books that they have each published.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Taoist compassion artwork; courtesy justgeneo.wordpress.com

The gently persuasive way—not beating others into submission, not bludgeoning, not eye-for-eye and tooth-for-tooth vengeance, but turning the other cheek, going the extra mile, giving more than is asked, killing the others’ “foeness” with kindness—is an ancient approach. It includes longsuffering, even self-sacrifice, loving your enemy, praying for those who persecute you. This is a Christian teaching, and is also ancient Taoist wisdom philosophy.

The Taoist classic text Tao Te Ching includes a number of lines about humility and not lording it over others, observations of patterns already recognized as very old wisdom 2500 years ago. TTC Chapter 68 is about the virtue of not contending; it speaks of “intelligent non-aggressiveness” and the “virtue of non-contention.” In Taoist philosophy one who accepts the “left tally, the debtor’s tally” (a symbol of inferiority in an agreement, getting the short end of the stick), humbly accepts the less prestigious position, which in the long run is the appearance the victor should have. To flaunt one’s victory sets a tone that brings resentment and reprisals. “Those who dispute are not skilled in Tao.” (TTC Chapter 81) Water flows downhill, and does not fight gravity. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Devi Prasad

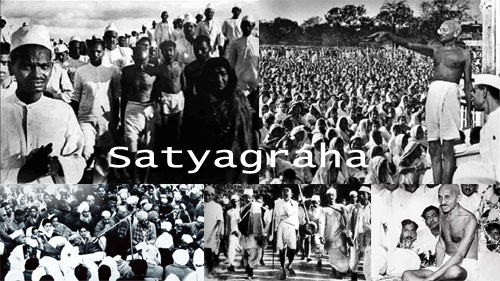

Gandhian civil resistance poster; courtesy peacetopia.com

To begin with I shall discuss some of the commonly used terms in connection with nonviolent action against oppression, and which are often mistakenly understood to be the same as the Satyagraha practiced and advocated by Gandhi. This is to try to point out the differences between the concepts these terms represent and how they are not quite the same as the concept of Satyagraha. These terms are passive resistance, non-cooperation, direct action, civil disobedience and non-resistance. My aim is not to minimise, even to the slightest degree, the merits, uses and strength of these methods, but to point out that in contrast to any of them Satyagraha is a complete philosophy, as well as the technique of fundamental social change. Whereas the philosophy of Satyagraha implies a holistic approach to both long term as well as immediate issues facing humankind, the practice of the above-mentioned concepts is, by definition, limited to particular situations without being necessarily related to other social or political problems.

Read the rest of this article »

by Chaiwat Satha-Anand

Book jacket art courtesy usip.org

From 1982 to 1984, Muslims from two villages in Ta Chana district, Surat Thani, in southern Thailand had been killing one another in vengeance; seven people had died. Then on January 7, 1985, which happened to be a Maulid day (to celebrate Prophet Muhammad’s birthday), all parties came together and settled the bloody feud. Haji Fan, the father of the latest victim, stood up with the Holy Qur’an above his head and vowed to end the killings. With tears in his eyes and for the sake of peace in both communities, he publicly forgave the murderer who had assassinated his son. Once again, stories and sayings of the Prophet had been used to induce concerned parties to resolve violent conflict peacefully. (1) Examples such as this abound in Islam. Their existence opens up possibilities of confidently discussing the notion of nonviolence in Islam. They promise an exciting adventure into the unusual process of exploring the relationship between Islam and nonviolence.

This chapter is an attempt to suggest that Islam already possesses the whole catalogue of qualities necessary for the conduct of successful nonviolent actions. An incident that occurred in Pattani, Southern Thailand, in 1975 is used as an illustration. Finally, several theses are suggested as guidelines for both the theory and practice of Islam and the different varieties of nonviolence, including nonviolent struggle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Acharya K.K. Chandy

Edward Hicks, “The Peaceable Kingdom”; courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.; nga.gov

Editor’s Preface: In the writings about Gandhi’s constructive programme, there are rarely any attempts made to compare it with historical precedents. Acharya Chandy has had the insight that William Penn’s Peaceable Kingdom of Pennsylvania is an apt precursor of a Gandhian community. This previously unpublished article continues our research project at the International Institute for Social History (IISG) in Amsterdam. Please consult that category for other articles, and the project’s statement of purpose. Please also see the notes at the end for acknowledgments, biographical details, and especially a note on the condition of the text. JG

In a context where the survival of the species through nuclear war or environmental degradation has become a main anxiety of the day, ignoring the warnings given by Christ and Gandhi would be to our peril as individuals and nations. Gandhi said, “In every state in the world today, violence, even if it were for so called defensive purposes only, enjoys a status which is in conflict with the better elements of life. The organisation of the best in society should be (our) aim, and this could be done only if we succeed in demolishing the status which has been given to militarism.” (Harijan, Augustus 24,1947) Uncompromising nonviolence, Gandhi said, is adequate to meet any situation – personal, social, political, economic, national and international. As Christ said, “Put up your sword, all who take the sword die by the sword … Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good.” (Matt. 26:52)

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

Anarcho-pacifist logo courtesy peaceofmindnews.com

The development of Christian Anarchism presaged the increasing convergence (but not complete merging) of pacifism and anarchism in the 20th century. The outcome is the school of thought and action (one of its tenets is developing thought through action) known as ‘pacifist anarchism’, ‘anarcho-pacifism’ and ‘nonviolent anarchism’. Experience of two world wars encouraged the convergence. But, undoubtedly, the most important single event to do so (although the response of both pacifists and anarchists to it was curiously delayed) was the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Ending as it did five years of ‘total war’, it symbolised dramatically the nature of the modern Moloch that man had erected in the shape of the state. In the campaign against nuclear weapons in the 1950s and early 1960s, more particularly in the radical wings of it, such as the Committee of 100 in Britain, pacifists and anarchists educated each other.

Read the rest of this article »