by Pope Francis

Your Eminence [Cardinal Peter Turkson]

I am delighted to convey my most cordial greetings to you and to all the participants in the Conference on Nonviolence and Just Peace: Contributing to the Catholic Understanding of and Commitment to Nonviolence, which will take place in Rome from the 11th to 13th of April 2016.

This encounter, jointly organized by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and Pax Christi International, takes on a very special character and value during the Jubilee Year of Mercy. In effect, mercy is “a source of joy, serenity and peace” (1), a peace which is essentially interior and flows from reconciliation with the Lord. (2) Nevertheless, the participants’ reflections must also take into account the current circumstances in the world at large and the historical moment in which the Conference is taking place, and of course these factors also heighten expectations for the Conference.

Read the rest of this article »

by John Dear

Daniel Berrigan marches for peace and against nuclear arms; New York City, 1982; photo courtesy AP

Rev. Daniel Berrigan, the renowned anti-war activist, award-winning poet, author and Jesuit priest, who inspired religious opposition to the Vietnam War and later the U.S. nuclear weapons industry, died on 30 April at age 94, just a week shy of his 95th birthday. He died of natural causes at the Jesuit infirmary at Murray-Weigel Hall in the Bronx. I had visited him just last week. He has long been in declining health.

Read the rest of this article »

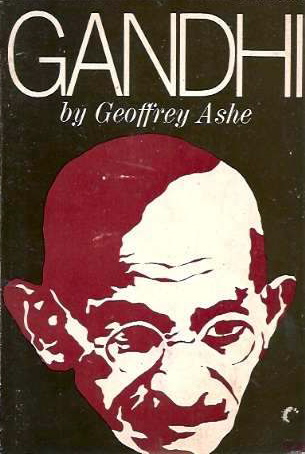

by Geoffrey Ashe

Dustwrapper art courtesy Stein & Day Publishing

Editor’s Preface: Gandhi was born in 1869 and as the centennial year of 1969 approached, pacifist and other publications worldwide used it as the occasion to re-evaluate Gandhi’s importance. The British cultural historian Geoffrey Ashe’s biography of Gandhi had been published to acclaim in early 1968 and Peace News published this article in their 16 August 1968 issue. It is the latest in our series of rediscoveries from the archives of the IISG in Amsterdam. Please see the notes at the end for references, acknowledgments, and further biographical information about Ashe. JG

Several months ago, Joan Baez described nonviolence as a flop, although she did qualify that by saying violence was a bigger flop. However, to my mind, we shouldn’t be downcast. By studying Gandhi’s nonviolence a little more carefully we can see what was right and wrong and make a fresh start. I am working on the Gandhi Centenary because I believe that some of the ideas which Gandhi explored in his career are still valuable and exciting, uniquely so; that these ideas can be restated and reapplied in the present context; but – what is perhaps the main thing – that no large-scale movement in this country has yet fully absorbed them or put them into practice.

Read the rest of this article »

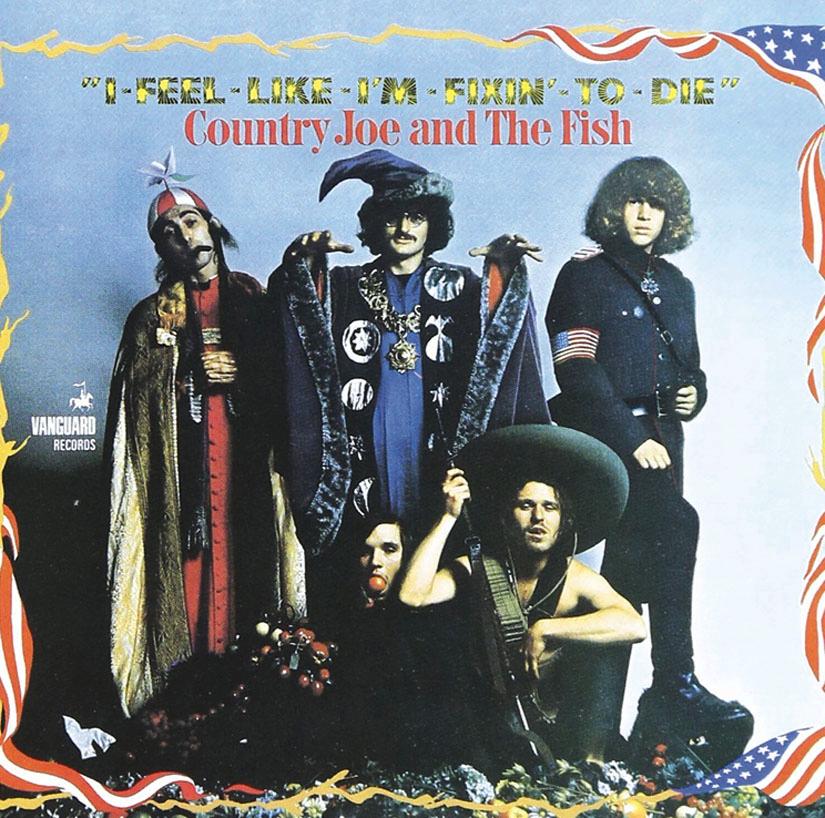

by Terry Messman

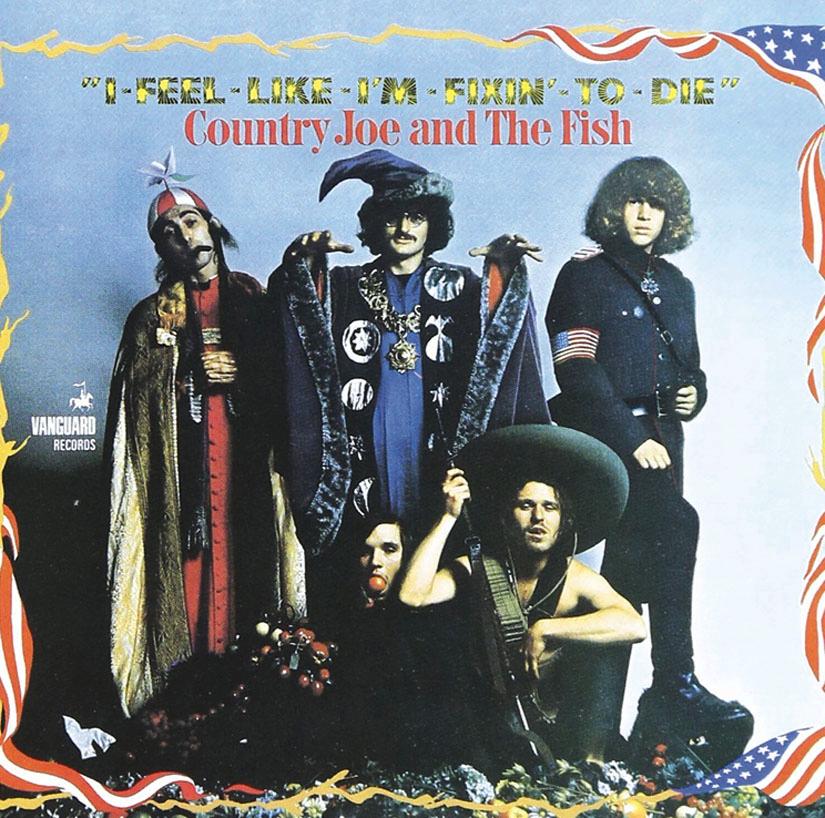

The second album Country Joe and the Fish album; Country Joe is seated front far right; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“Women coming home from the Vietnam War never were the same after their wartime experiences. They were shoved into a horrific, unbelievable experience. That’s what I wrote about in the song: ‘A vision of the wounded screams inside her brain, and the girl next door will never be the same.’” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: You first sang “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” on the streets of Berkeley during the Vietnam War in 1965. Fifty years later, you sang it at an anti-nuclear protest at Livermore Laboratory on the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Could you have imagined in 1965 that your song would still have so much meaning today?

Country Joe McDonald: Actually, I find the concept of 50 years incomprehensible. But it’s indisputable because I have children and some of those children have children and I know that the math is right. And I just finished an album and the title of it is 50 because it’s 50 years since the first album. It’s called Goodbye Blues. I didn’t die, so there you are. I’m still alive and I’m still doing something. Filling a need helps a lot, and it keeps me sane.

Read the rest of this article »

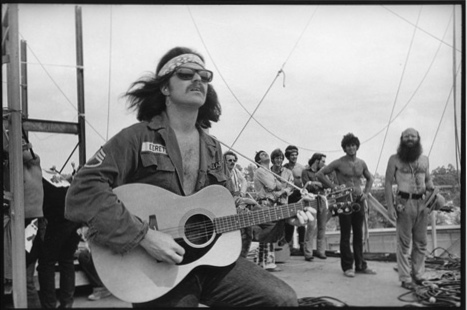

by Terry Messman

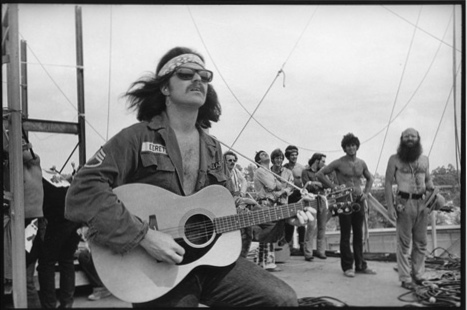

Country Joe McDonald sings “Fixin’ to Die Rag” for 300,000 people at Woodstock; photo by Jim Marshall, courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“It was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, London, and San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. It was a wonderful thing to happen. And I’m still a hippie: peace and love!” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: During the Vietnam War, and while caring for the victims of PTSD and Agent Orange in the years after the war, Lynda Van Devanter and other Vietnam combat nurses helped many veterans to survive. Your song about Van Devanter says that the combat nurse is everybody’s savior but her own. Then it asks, “Who will save her now?”

Country Joe McDonald: Yes, who will save her now?

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Country Joe McDonald sings anti-war songs; Livermore Lab, Hiroshima Day, August 6, 2015; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Country Joe McDonald composed one of the most acclaimed peace anthems of the Vietnam era, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” a rebellious and uproarious blast against the war machine. The song’s anti-war message seems more timely than ever, with its savagely satirical attack on the arms merchants, the military and the White House. “Fixin’ to Die Rag” condemns the architects of war and the military-industrial complex in bitterly sarcastic terms.

Come on Wall Street, don’t move slow

Why man, this is war au-go-go!

There’s plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade.

Recently, a major new book by Craig Werner and Doug Bradley, We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War, [Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015] ranked hundreds of Vietnam-era songs and listed “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” by Country Joe and the Fish as one of the two most important songs named by Vietnam veterans, right after “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” by the Animals. “The soldiers got it,” write co-authors Werner and Bradley about Country Joe’s song. Michael Rodriguez, an infantryman with the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, said: “Bitter, sarcastic, angry at a government some of us felt we didn’t understand — ‘Fixin’ to Die Rag’ became the battle standard for grunts in the bush.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Rasoul Sorkhabi

Dustwrapper art courtesy Shambhala Publications; shambhala.com

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi in 1948 (sixty years ago as of this writing) and the renowned Trappist monk and author Thomas Merton was killed in a tragic accident in 1968 (forty years ago). These anniversaries are valuable opportunities to reflect on the legacies, works, and teachings of these two great men of peace. Gandhi has influenced many minds and movements of the twentieth century. In this article, we review Merton’s impressions of Gandhi and how they are helpful for our century and generation.

Thomas Merton, born in 1915, was 46 years younger than Gandhi. Merton spent the first two decades of his life in France, UK and USA. In 1939, he received his MA in English literature from Columbia University, and the following year accepted a teaching position at the Franciscan run Saint Bonaventure University in southwest New York State. In 1942 he decided to become a priest and entered the Abbey of Gethsemane, a Trappist monastery in Kentucky; the Trappist are strict observance Franciscans, and having taught at St. Bonaventure might have influenced his decision. Merton, or rather Father Louis as he was to be called at Gethsemane, lived the rest of his life there, a quiet and contemplative life in an inspiring natural environment. He kept journals and published innumerable essays, poems, and books. His autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, published in 1948 became a best seller. In the 1960s, Merton was attracted to Eastern religious thoughts and traditions, including Gandhi’s ideas.

Read the rest of this article »

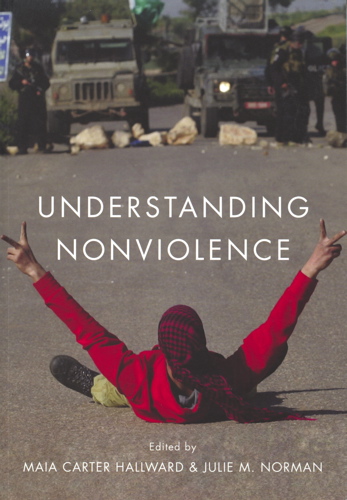

by Tristan K. Husby

Dustwrapper art courtesy Polity Press; politybooks.com

The phrase “Those who can’t do, teach” is so well ingrained in the English vernacular that there is a range of variations, such as “Those who can’t teach, go into administration” or “Those who can’t teach, teach gym.” Knowledge of this phrase is so widespread that a current sit-com about incompetent teachers is simply titled “Those Who Can’t”. Less well known is that the Irish intellectual, playwright, and wit George Bernard Shaw coined this phrase. His original rendition, “He who can, does. He who can’t, teaches”, was one of the aphorisms in his Maxims for Revolutionists. Another axiom from the same book is “Activity is the only road to knowledge.”

That last sums up a great deal of the history of nonviolence. For to a great degree the history of nonviolence is a history of organizers, activists, and leaders first teaching others why nonviolence is an effective method and then working together with those people for change. The recent anthology, Understanding Nonviolence, edited by Maia Carter Hallward and Julie M. Norman (Malden, MA: Polity, 2015) aims to help aid in the discussion; it is explicitly pedagogical, with discussion questions and suggestions for further reading included in each chapter. Furthermore, jargon is kept to a minimum and the authors use endnotes sparingly. However, labeling this book as pedagogical does not mean that it is contains exercises for training nonviolent actions or flowcharts for planning strategies. Rather, this book is pedagogical in that it aims to help students study nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Surur Hoda

Dustwrapper art courtesy Harper Publishing; harpercollins.com

Gandhi’s visions of Gram Swaraj, self-sufficient but inter-linked village republics with decentralised small-scale economic structures and participatory democracy, left him immediately at odds with those in and outside the Indian National Congress who were seeking to develop India into a modern industrial nation state. To Gandhi, political freedom was merely the first step towards attainment of real independence, namely social, moral and economic freedom for seven hundred thousand villages. ‘If the villages perish India will perish,’ he had said. But the majority of academically trained, modern economists called his vision ‘retrograde’. Some extremists even described it as ‘reactionary’ or ‘counter-revolutionary’ and accused him of aiming to put the clock back.

Many of those who admired Gandhi’s skill in leading the struggle for national liberation reluctantly tolerated his economic views as the price to pay for his political leadership. They were sold on the concept of large-scale urban industrialisation and mass production. They failed to understand Gandhi’s economic insights and criticised him by saying ‘Whatever Gandhi’s merit as “Father of the Nation”, he simply does not understand economics.’

Yet almost a quarter of a century after Gandhi assassination, the German born economist E. F. Schumacher, when delivering the Gandhi Memorial Lecture at the Gandhian Institute of Studies at Varanasi (India) in 1973, described him as the greatest ‘People’s Economist.’ In his opening remarks, Schumacher told this story: ‘A famous German conductor was once asked who he considered the greatest of all composers. “Unquestionably Beethoven” was his answer. He was then asked, “Would you not even consider Mozart?” He said, “Forgive me. I thought you were referring to the others.”’ Drawing a parallel Schumacher said the same question might he put as to who was the greatest economist. ‘Unquestionably Keynes,’ he would reply, and be immediately asked, ‘Would you not even consider Gandhi?’ His answer would be, ‘Forgive me, I thought you were referring to the others.’

Read the rest of this article »

by Fred J. Blum

Logo Shanti Sena World Peace Network; courtesy mettacenter.org

Editor’s Preface: The Peace Brigade was organized in 1981 by Narayan Desai and others in London, as an extension of the Shanti Sena, or nonviolent peace force, which Vinoba Bhave had founded in India in the 1950s. Bhave had, of course, taken his name and concept from Gandhi and more specifically from Gandhi’s Constructive Programme. This previously unpublished article makes clear that activists in the U.S. nonviolence and peace movements were already thinking of forming their own chapters as early as 1961, the date on the manuscript. The Brigade still continues in many countries under various names such as the World Peace Brigade, Peace Brigades International, Muslim Peacemaker Teams, etc.. The article is another in our series from the IISG archive in Amsterdam. For further information and references please consult the notes at the end of the article. JG

What is nonviolence? When I thought about how I wanted to start this discussion I felt a need to give some initial broad definition. The first that came to my mind was “to refuse to use violence and to substitute for it other means.” As soon as I had written it down, I felt that the term “to use violence” was very limiting, and expressed a mode of thinking so prevalent today that none of us could easily escape from it, namely a thinking in instrumental terms: of using techniques, of making “things” an instrument for our purpose, for controlling our environment, etc.

Read the rest of this article »