On Christian Nonviolence: Becoming the New Creature

by Eileen Egan

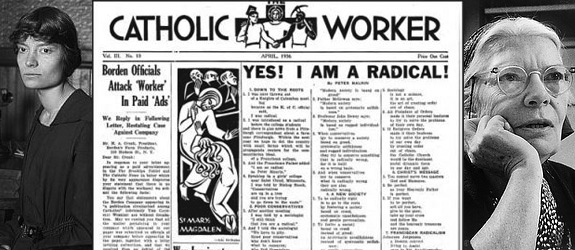

Photo collage with CW masthead; artist unknown; courtesy of the CW

Nonviolence has a negative, passive ring to it that its adherents have been attempting to erase by prefixing to it the adjective “militant.” Regrettably, it is the only current term in general usage in English. It corresponds to the Gandhian ahimsa, or non-injury, and carries the necessary message of unwillingness to injure or kill other creatures. For Western adherents of ahimsa or nonviolence who are not vegetarians, the unwillingness applies only to humans. The nonviolent person is not supine before an insane attack. The defense of a third party often involves the interposing of the body of the nonviolent person, with no intent of inflicting harm. Gandhi coined the term satyagraha, or truth-force, to describe a nonviolent campaign for human rights and freedom. As “God is Truth and Truth is God” in Gandhi’s thinking, the inference was that only godly or moral force would be employed by satyagrahi, participants in the nonviolent movement. Martin Luther King’s term, “soul-force” is a satisfactory one for most adherents of nonviolence.

A commitment to nonviolence as a way of life and of achieving change has deep implications for personal life and personal relationships, for community and social actions, and for the conduct of the nation. A striking example of the implications of the acceptance of nonviolence for one’s personal life is narrated in The Book of Ammon, the autobiography of Ammon Hennacy. (1) In July 1917, as a 24 year-old prisoner, Ammon arrived at Atlanta Federal Penitentiary to serve a two-year sentence for anti-draft activity. This was separate from a sentence, to be served later, for his own refusal to register for the draft. Ammon, prisoner 7438, was not long in Atlanta when he stirred things up. He led his fellow-prisoners in a mass refusal to appear at the mess hall as a protest against rotten food. For this action, Ammon was condemned to solitary confinement. Though his teeth began to ache, he could not persuade the warden to allow him to see a dentist. Ammon wrote that, in his heart, he longed for a weapon and “mentally listed those whom I desired to kill when I was free.”

Ammon was allowed a Bible and it became his only companion in “the hole.” He read the New Testament many times and recalled that he went over the Sermon on the Mount scores of times. He pondered the series of great “contradictions” put forward by Jesus in the Sermon. “You have heard it said . . . But I say to you” as for example, “You have heard it said, ‘Love your friends and hate your enemies.’ But I say to you: Love your enemies and pray for those who mistreat you so that you will become sons of your Father in heaven”.

Emulating Gandhi, Ammon practiced each truth as soon as he apprehended it. He began to try to love everyone. He wrote, “In my heart now after six months I could love everybody in the world but the warden, but if I did not love him then the Sermon on the Mount meant nothing at all.” The solution finally came to him. “Here I am locked up in a cell. The warden was never locked up in any cell and he never had a chance to know what Jesus meant, so I must not blame him. Now the whole thing was clear. I would never have a better opportunity to try out the Sermon on the Mount than right now in my cell. Here was deceit, hatred, lust, murder and every kind of evil in this prison.”

The Turning and Suffering

The months in solitary were the turning point for the remainder of Ammon’s life. He took to heart the specific responses of the nonviolent person as detailed in the “contradictions”: the commands to refrain from anger, to let go of one’s cloak to the one who would snatch one’s coat, to go two miles with the one who would force one to go one mile, to love the enemy. He realized that the practice of nonviolence involves a “turning away” from such natural responses as anger, striking back when struck, or defending the right to one’s property. The “turning away” seems to be, in fact, the first step in the conversion to a life of Christian nonviolence; the second step being the “turning to,” the striving for, unconditional love.

Ammon used to quote a saying from our friend, Fr. John Hugo, “You love God as much as you love the person you love the least”. Then Ammon would add, “That is what I learned in Atlanta from that warden.” In the end, Ammon’s witness reached the warden. When the Superintendent attacked his obduracy (he refused to become an informer in return for freedom) and called him a fool and a coward, the warden came to his defense. As Ammon explained, “The warden had called me names often but he disliked to hear an outsider do so. ‘If he’s a fool or a coward,’ the warden asserted, ‘he must be a different kind, for no one ever stood more than three months in the hole without giving in. He must he God’s fool or God’s coward.’”

What Ammon demonstrated by his “turning from–turning to” is the rejection of the “old creature” and the putting on of the “new creature” of the gospel. The recognition of the need to be a “new creature” is crucial to any change; it makes us aware of the responses of the “old creature.” Only through such awareness can we integrate into our lives the constant struggle for transcendence and the unending search for a loving, nonviolent, non-excluding identity, whose loyalty is not to a particular part of the human family, but to the entire species.

The unexpected responses of the new creature have shocked and even scandalized people since the beginnings of Christianity. Justin the Philosopher described the change that came over him and others when they became followers of Jesus: “We who were filled with war, and mutual slaughter, and every wickedness, have each through the whole earth changed our warlike weapons – our swords into ploughshares, and our spears into implements of tillage – and we cultivate piety, righteousness, philanthropy, faith, and hope, which we have from the Father Himself through Him who was crucified.” In a time when love and loyalty were owed only to tribes or to an empire, love of humanity was a revolutionary ideal. This love, of course, is agape, defined by Martin Luther King as “creative, redemptive good will for all.” It is distinguished from eros and is related to the spiritual “love feast”, which brought the Christian community together. Justin became a martyr in Rome in the year 165 CE. Along with so many others, he found peace in holding to truth and suffering for it.

One of the most succinct descriptions of nonviolence was formulated by Gandhi as “adherence to Truth and insistence upon it by self-suffering.” He called satyagraha, “the argument of suffering”, and saw it as based upon “an implicit belief in the absolute efficacy of innocent suffering”. The example of Jesus was termed by Gandhi “nonviolence par excellence”. In Young India he wrote, “Christ died on the Cross with a crown of thorns on his head, defying the might of a whole empire. And if I raise resistance of a nonviolent character, I simply and humbly follow in the footsteps of the great teacher.” Gandhi saw more vividly than many Christians that innocent suffering is the very engine of the world.

Much is known of Gandhi’s resistance to colonial rule in India and of the various nonviolent campaigns he initiated for the freeing of the country. Less well known are the campaigns against the evils within Indian society, notably the cause of the “untouchables”. A cardinal point of the Indian National Congress Party platform of 1930 was the eradication of untouchability in Indian life. These campaigns were designed not to punish those who upheld untouchability but to enlighten and finally to convert them. Patient self-suffering rather than the infliction of suffering marked satyagraha campaigns. One of the most telling campaigns was the long-drawn out Vykom Temple satyagraha in Kerala, South India. Besides being excluded from the use of village wells, untouchables were forbidden entry into temples or into temple grounds. Gandhi renamed the outcastes or untouchables harijans, meaning “children of God”.

In Kerala, the harijans were not allowed to use public roadways that cut through the grounds of the Vykom Temple, which meant that the harijans had to take a circuitous route to their homes from their work in the fields. The long walk lengthened their workday and depleted their energies. The temple Brahmins were firm in their refusal to allow passage to the harijans, and so a campaign was planned.

Joan Bondurant relates the details in her study of satyagraha, Conquest of Violence. (2) A satyagraha camp, or ashram, was set up in the Spring of 1924 for the housing of volunteers, most of them high-caste Brahmin Hindus. They would make their way with a few harijans, to the point where the road crossed the temple grounds. They were turned back repeatedly. Eventually, local authorities were asked to provide police protection to the temple Brahmins, and the police set up barricades to confront the demonstrators. Month after month, the satyagrahi would walk up to the barricades and stand there as witnesses. When the monsoon rains flooded the area, the police maintained their positions in boats. The demonstrators stood vigil in three-hour shifts with the water waist or shoulder-high. After a visit by Gandhi in April 1925, local authorities ordered the removal of the barricades. This meant that anyone could utilize the roadways through the temple grounds without obstruction, but the harijans could still not enter the temple precincts. To the astonishment of the Brahmins, the satyagrahis and the harijans maintained their witness outside the temple grounds. They made no move to use the shorter roads.

Months went by and the life of the ashram went on, with prayer meetings emphasizing the religious tone of the satyagraha action. The Brahmins took counsel with each other and reached their own decision. They announced to the demonstrators: “We cannot any longer resist the prayers that have been made to us and we are ready to receive the untouchables”. This campaign was considered a turning point in the opening of temple grounds and eventually of temples to the harijans.

Satyagraha is the revolution that lasts.

Bondurant quotes Gandhi in relation to satyagraha actions. ”Satyagraha,” Gandhi said in the course of the Vykom Temple campaign, “is a process of conversion. The reformers do not seek to force their views upon the community; they strive to touch its heart.” Temple entry for the harijans was achieved all over India by such campaigns. Such entry was an enormously important symbolic step towards the removal of other restrictions. Such nonviolent revolutions effectuated permanent changes in overturning age-old customs since the conscience of the opponent was respected. Time was allowed for a deep change of heart. Satyagraha is the revolution that lasts.

The Vykom Temple campaign calls to mind the great civil rights campaigns of Martin Luther King, Jr., which were directed against similar specific evils in our society, and achieved integration and voting rights. As in India, society takes a long time to gain true social justice for those whom it has wronged for generations. Cesar Chavez also took inspiration from Gandhi in his nonviolent campaigns on behalf of farm workers. His methods included marches, pilgrimages, secondary boycotts and resistance to unjust picketing laws, and have brought the plight of the farm worker to the forefront of the American conscience.

Nonviolence and Politics

Nonviolent action takes on a different character when it is directed against a political evil and involves the nation. Political resistance generates incendiary passions where nonviolence becomes a tender plant that is easily crushed. The 1942 “Quit India” slogan of the Indian Congress had unacceptable implications for the warring mother country, Britain, which had plunged India’s millions into World War II without deferring to their wishes. The “Quit Vietnam” campaign of the American peace movement had similar political implications for the American government, which had drawn its citizenry into a war without a formal declaration of war. In such situations, where a political establishment is challenged, and resisted, arrests and imprisonment are to be expected.

In India, 400 Congress leaders were in jail by the end of World War II, as well as 25,000 others convicted of individual civil disobedience. But there were those who chose to express their resistance to British rule in more dramatic ways. They raided and burned the symbols of the Raj by which their lives were controlled, among them police stations and courts along with their records. Gandhi never wavered from nonviolence, cautioning against any acts of resistance involving crimes, He had told his followers, “Satyagraha largely appears to the public as Civil Disobedience or Civil Resistance. It is civil in so far as it is not criminal.”

Acts Of Resistance

American resistance to the Vietnam War sometimes took the same dramatic route as Indian resistance a quarter of a century earlier, the burning of government property, in this case, draft records. There is no doubt as to the willingness of most of the draft board raiders and draft record burners to accept suffering in the Gandhian tradition. There is no doubt of the dramatic impact such actions had on the American public. There are those who take Gandhi, and the rules he laid down as the founder of satyagraha, with the utmost seriousness. He gave his life to the development of nonviolence in the tradition of love and redemptive self-suffering and his principles cannot be lightly set aside. Among those basic rules were: complete openness, not only with satyagrahi but also with the opponent, the scrupulous maintenance of the civil character of the resistance by the avoidance of criminal acts, and the willing acceptance of arrest and imprisonment.

In a discussion of draft board raids at the 1989 Conference of the War Resisters International, David McReynolds, leader of the American affiliate, War Resisters League, raised two salient queries; is it justifiable to destroy the records of those with whom we disagree, even though we are convinced of the evil of their cause, and is it justifiable to destroy the draft records of individuals without giving each individual a chance to exercise his own conscience in the matter. He also made the point that removing some draft records only resulted in having others drafted.

Is there a point in raising these questions, which are still debated and which are still unresolved in the minds of many? The United States did quit Vietnam and the war is over. To many of us, the questions of means, of pure civil disobedience and of pure nonviolent resistance, not involving criminal acts, is crucial. It is crucial because the time has come to oppose an evil policy of our American government, a policy that threatens the very existence of the human family and the planet itself.

The evil is of course the nuclear stockpile built up by our government on the taxes of its citizens. Nuclear warheads are cached in bases around the globe so that the very planet pulses with death. Planes carry “payloads” of bombs that could make of any large city an “instant Auschwitz”, where the gassed bodies of 4,000,000 persons mostly Jews were rendered into ashes. American citizens, supposedly living in a democratic open society, only become aware of such dread potentialities by accident. In the spring of 1966, a plane carrying four nuclear bombs met with a refueling accident over Palomares, Spain. One bomb was lost in the Mediterranean and was recovered only after a frantic convergence of naval vessels. Pentagon authorities claimed that the bomb was of the magnitude of 2 megatons, although a scientist told us that it was 20 megatons. According to Dr. Tom Stonier, author of Nuclear Disaster, a 20-megaton bomb, dropped on Columbus Circle, could incinerate 9,000,000 New Yorkers. There are on hand sufficient instruments of genocide of this type to vaporize the 2,000 major cities of our planet.

These facts are presented not to excite fear, but to make real and urgent the need to oppose American nuclear policy through the means of nonviolence. True nonviolence cannot be blurred or secret; it must be the nonviolence of openness, of love; it must be ready for redemptive suffering. It must be, in a word, the resistance of the “new creature” of the gospel.

Ways to Resist

Imagination is needed to mount civil disobedience and civil resistance campaigns against so immense and pervasive an evil as nuclear stockpiles. A simple first step would be for people aware of the evil to wear a button with the image of a nuclear explosion and a two-word declaration: “WITHOUT US”. Certainly the members of the American Catholic community, if they heed the pronouncement of the universal church, should begin at this point. The means of fasting is always there. In fasting, the body feeds on itself; it burns itself. As Gandhi said, “Love does not burn others, it burns itself.” We could publicly fast against the policy of preparing to burn other members of the human family. Already there are programs of tax resistance among Americans whose consciences are affronted by a hundred billion dollar annual “defense” budget. Against their will, their taxes are being utilized in a nuclear “overkill” policy. Our nation, which has the resources to meet the needs of the poor at home and around the world, has chosen to pour its resources into an obscene stockpile of death. So Jesus goes hungry, thirsty, homeless, and we are under judgment.

Possibly a march might awaken the consciences of Americans. Openness and persuasion should characterize the effort so as to alienate as little as possible those who find their security under the “nuclear umbrella.”

The American Catholic community has received unmistakable guidance regarding the American nuclear stockpile. How many times have we heard repeated the one ban pronounced in the whole of the second Vatican Council by the bishops of the world, the ban on indiscriminate warfare? “Any act of war,” said the bishops in The Church in the Modern World, “aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities or extensive areas, along with their population, is a crime against God and man himself, it merits unequivocal condemnation.” This statement has deep implications for all members of the American Catholic community, but in a particularly poignant way for those who call themselves nonviolent.

What importance does a personal commitment to nonviolence have, or even how important is a commitment to nonviolent methods of resolving social injustices, if we do not dissociate ourselves from the unspeakably violent stance of our national community? And after dissociating ourselves, must we not find ways to offer disobedience and resistance to awaken the consciences of millions of Americans now entrapped in the nuclear policy?

The New Creature of the gospel, who abjures hatred of any sort, who does not seek revenge, who wills the well being of all, including the enemy, attempts to live his/her life as part of the great stream of love flowing from the Creator to His creatures. The new creature is not concerned simply with the saving of his/her own soul but with “God’s way of saving the World.” The Son of Man reconciled humankind to God and to itself by accepting suffering, not by inflicting suffering. The central act of our religious life is the commemoration of the act by which Jesus died. As Jesus told us, “The bread that I will give is my flesh for the life of the world,” Let us show by every possible means that we are against the threat or actuality of mass death, and that we truly eat this bread “for the life of the world.”

Endnotes: (JG)

(1) Ammon Hennacy (1893-1970) was an Irish-American, Christian anarcho-pacifist. He founded the radical, nonviolent community in Salt Lake City, Joe Hill House, and was a lifelong friend of Dorothy Day’s, and considered a member of the extended CW family. The Wikipedia article is worth consulting, and lists his publications. His autobiography is: The Autobiography of a Catholic Anarchist, New York: Catholic Worker Books, 1954.

(2) Joan Bondurant’s Conquest of Violence is considered by some as one of the finest studies of Gandhian civil resistance. The new revised edition is still in print (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988). Bondurant led a colorful life, having been a spy In India for the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor of the CIA) during World War II, which is where she met Gandhi and became familiar with his satyagraha campaigns. After the war she took a PhD degree in political science, which she taught at Berkeley. Conquest explores the nature of political conflict and the ways in which satyagraha might redefine its meaning and influence its application.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Eileen Egan (1912-2000) was born in Wales but moved as a child to New York with her family. She was a journalist and social activist, and co-founder of the American pacifist organization PAX as well as chairperson of its successor PAX Christie. A lifelong friend of Dorothy Day she lived for a time in Catholic Worker communities and wrote extensively for the CW newspaper, including many articles specifically on Gandhian nonviolence. Her books include not only studies of Dorothy and the CW, but also several on Mother Teresa. Her Wikipedia article gives more biographical information and a list of her publications. This article, CW, May 1975; pp. 1, 3, & 12; courtesy of the CW and Marquette University.