Nonviolence after Gandhi: The Death of Martin Luther King Jr.

by Bayard Rustin

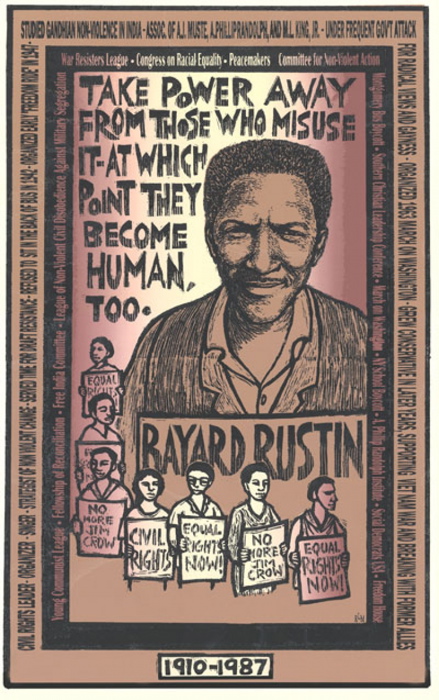

Rustin poster courtesy American Friends Service Committee; afsc.org

Editor’s Preface: Bayard Rustin (1912-1987) was one of the leading proponents of nonviolence in the U. S. civil rights era. He wrote this article just weeks after the assassination of Dr. King on 4 April 1968. For acknowledgments and further information about Rustin please consult the editor’s note at the end. JG

The murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. has thrust a lance into the soul of America. The pain is most shattering to the Negro people. We have lost a valiant son, a symbol of hope and an eloquent spirit that inspired masses of people. Such a man does not appear often in the history of social struggle. When his presence signifies that greatness can inhabit a black skin, those who must deny this possibility stop at nothing to remove it. Dr. King now joins a long list of victims of desperate hate in the service of insupportable lies, myths, and stereotypes.

For me, the death of Dr. King brings deep personal grief. I had known and worked with him since the early days of the Montgomery bus protest in 1955, through the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Prayer Pilgrimage in 1957, the youth marches for integrated schools in 1958 and 1959 and the massive March on Washington in 1963.

Though his senior by 20 years, I came to admire the depth of his faith in nonviolence, in the ultimate vindication of the democratic process and in the redeeming efficacy of social commitment and action. And underlying this faith was a quiet courage grounded in the belief that the triumph of justice, however long delayed, was inevitable. Like so many others, I watched his spirit take hold in the country, arousing long-slumbering consciences and giving shape to a new social movement. With that movement came new hopes, aspirations, and expectations. The stakes grew higher. At such a time, so great a loss can barely be sustained by the Negro people. But the tragedy and shame of April fourth darkens the entire nation as it teeters on the brink of crisis. And let no one mistake the signs: our country is in deadly serious trouble. This needs to be said because one of the ironies of life in an advanced industrialized society is that many people can go about their daily business without being directly affected by the ominous rumblings at the bottom of the system.

Yet we are at one of the great crossroads in our history and the alternatives before us grow starker with every summer’s violence. In moments like these there is a strong temptation to succumb to utter despair and helpless cynicism. It is indeed hard to maintain a clear perspective, a reliable sense of where events are heading. But this is exactly what we are called upon to do. Momentous decisions are about to be made—consciously or by default—and the consequences will leave not one corner of this land, nor any race or class, untouched.

Where, then, do we go from here?

We are a house divided. Of this Dr. King’s murder is a stunning reminder. Every analysis, strategy, and proposal for a way out of the American dilemma must begin with the recognition that a perilous polarization is taking place in our society. Part of it is no doubt due to the war in Vietnam, part to the often-remarked generational gap. But generations come and go and so do foreign policies. The issue of race, however, has been with us since our earliest beginnings as a nation. I believe it is even deeper and sharper than the other points of contention. It has bred fears, myths, and violence over centuries. It is the source of dark and dangerous irrationality, a current of social pathology running through our history and dimming our brighter achievements.

Most of the time the reservoir of racism remains stagnant. But— and this has been true historically for most societies—when major economic, social or political crises arise, the backwaters are stirred and latent racial hostility comes to the surface. Scapegoats must be found, simple targets substituted for complex problems. The frustration and insecurity generated by these problems find an outlet in notions of racial superiority and inferiority. Very often we find that the most virulent hostility to Negroes exists among ethnic groups that only recently ‘made it’ themselves or that are still near the bottom of the ladder.

They need to feel that somebody is beneath them. (This is a problem, which the labor movement has had to face more acutely perhaps than any comparable institution in American life. And it is a problem which some of labor’s middle-class critics have not had to cope with at all.)

Negroes are reacting to this hostility with a counter-hostility. Some say the white man has no ‘soul’; others say he is barbaric, uncivilized; others proclaim him racially inferior. As is so often the case, such a reaction is the exaggerated obverse of the original action.

And in fact it incorporates elements of white stereotypes of Negroes. (‘Soul’ for example, so far as it is definable, seems to consist in part of rhythm, spontaneity, pre-industrial sentimentality, a footloose anti-regimentation, etc.— qualities attributed to Negroes by many whites, though in different words.)

This reaction among Negroes is not so new as many white people think. What is new is the intensity with which it is felt among some Negroes and the violent way it has been expressed in recent years. For this, the conservatives and reactionaries would blame the civil rights movement and the federal government. And in the very specific sense, we must conclude that they are right.

One effect of the civil rights struggle in the past 10 years has been to convince a generation of young Negroes that their place in society is no longer pre-determined at birth. We demonstrated that segregationist barriers could be toppled, that social relations were not fixed for all time, that change was on the agenda. The federal government reinforced this new consciousness with its many pronouncements that racial integration and equality were the official goals of American society.

The reactionaries would tell us that these hopes and promises were unreasonable to begin with and should never have been advanced. They equate stability with the preservation of the established hierarchy of social relations, and chaos with the reform of that unjust arrangement. The fact is that the promises were reasonable, justified and long overdue. Our task is not to rescind them—how do you rescind the promise of equality?—but to implement them fully and vigorously.

This task is enormously complicated by the polarization now taking place on the race issue. We are caught in a vicious cycle; inaction on the poverty and civil rights fronts foments rioting in the ghettoes: the rioting encourages vindictive inaction. Militancy, extremism and violence grow in the black community; racism, reaction and conservatism gain ground in the white community.

Personal observation and the law of numbers persuade me that a turn to the ‘right’ comprises the larger part of this polarization. This of course is a perilous challenge not only to the Negro but also to the labor movement, to liberals and civil libertarians, to all the forces for social progress. We must meet that challenge.

Meanwhile, a process of polarization is also taking place within the Negro community and, with the murder of Dr. King, it is likely to be accelerated.

Ironically and sadly, this will occur precisely because of the broad support Dr. King enjoyed among Negroes. That support cut across ideological and class lines. Even those Negro spokesmen who could not accept, and occasionally derided, Dr. King’s philosophy of nonviolence and reconciliation, admired and respected his unique national and international position. They were moved by his sincerity and courage. Not perhaps since the days of Booker T. Washington—when 90 per cent of all Negroes lived in the South and were occupationally and socially more homogeneous than today—had any one man come so close to being the Negro leader. He was a large unifying force and his assassination leaves an enormous vacuum. The diverse strands he linked together have fallen from his hands.

The murder of Dr. King tells Negroes that if one of the greatest among them is not safe from the assassin’s bullet, then what can the least of them hope for? In this context, those young black militants who have resorted to violence feel vindicated. “Look what happened to Dr. King”, they say, “he was nonviolent, he didn’t hurt anybody. And look what they did to him. If we have to go down, let’s go down shooting. Let’s take whitey with us.”

Make no mistake about it: a great psychological barrier has now been placed between those of us who have urged nonviolence as the road to social change and the frustrated despairing youth of the ghettoes. Dr. King’s assassination is only the latest example of our society’s determination to teach young Negroes that violence pays. We pay no attention to them until they take to the streets in riotous rebellion. Then we make minor concessions—not enough to solve their basic problems, but enough to persuade them that we know they exist. “Besides”, the young militants will tell you, “this country was built on violence. Look at what we did to the Indians. Look at our television and movies. And look at Vietnam. If the cause of the Vietnamese is worth taking up guns for, why isn’t the cause of the black man right here in Harlem?”

These questions are loaded and oversimplified, to be sure, and they obscure the real issues and the programmatic direction we must take to meet them. But what we must answer is the bitterness and disillusionment that give rise to these questions. If our answers consist of mere words, they will fall on deaf ears. They will not ring true until ghetto-trapped Negroes experience significant and tangible progress in the daily conditions of their lives—in their jobs, income, housing, education, health care, political representation etc. This must be understood by those often well-meaning people who, frightened by the polarization, would retreat from committed action into homilies about racial understanding.

We are indeed a house divided. But the division between race and race, class and class, will not be dissolved by massive infusions of brotherly sentiment. The division is not the result of bad sentiment and therefore will not be healed by rhetoric. Rather the division and the bad sentiments are both reflections of vast and growing inequalities in our socio-economic system—inequalities of wealth, of status, of education, of access to political power. Talk of brotherhood and ‘tolerance’ (are we merely to ‘tolerate’ one another?) might once have had a cooling effect, but increasingly it grates on the nerves. It evokes contempt not because the values of brotherhood are wrong—they are more important now than ever—but because it just does not correspond to the reality we see around us. And such talk does nothing to eliminate the inequalities that breed resentment and deep discontent.

The same is true of most ‘Black Power’ sloganeering, in which I detect powerful elements of conservatism. Leaving aside those extremists who call for violent ‘revolution’, the Black Power movement embraces a diversity of groups and ideologies. It contains a strong impulse toward withdrawal from social struggle and action, a retreat back into the ghetto, avoidance of contact with the white world. This impulse may, I fear, be strengthened by the assassination of Dr. King.

This brand of Black Power has much in common with the conservative white American’s view of the Negro. It stresses self-help (“Why don’t those Negroes pull themselves up by their own bootstraps like my ancestors did?”). It identifies the Negro’s main problems in psychological terms, calls upon him to develop greater self-respect and dignity by studying Negro history and culture and by building independent institutions.

In all of these ideas there is some truth. But taken as a whole, the trouble with this thinking is that it assumes that the Negro can solve his problems by himself, in isolation from the rest of the society. The fact is, however, that the Negro did not create these problems for himself and he cannot solve them by himself.

Dignity and self-respect are not abstract virtues that can be cultivated in a vacuum. They are related to one’s job, education, residence, mobility, family responsibilities and other circumstances that are determined by one’s economic and social status in society. Whatever deficiencies in dignity and self-respect may be laid to the Negro are the consequence of generations of segregation, discrimination and exploitation. Above all, in my opinion, these deficiencies result from systematic exclusion of the Negro from the economic mainstream.

This exclusion cannot be reversed—but only perpetuated—by gilding the ghettos. A “separate but equal” economy for black Americans is impossible. In any case, the ghettoes do not have the resources needed for massive programs of abolishing poverty, inferior education, slum housing, and the other problems plaguing the Negro people. These resources must come primarily from the federal government, which means that the fate of the Negro is unavoidably tied to the political life of this nation.

It is time, therefore, that all of us, black and white alike, put aside the rhetoric that obscures the real problems. It is precisely because we have so long swept these incendiary problems under the rug that they are now exploding all around us, insisting upon our attention. We can divert our eyes no longer. The life and death of Martin Luther King are profoundly symbolic. From the Montgomery bus protest to the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, his career embodies the internal development, the unfolding, the evolution of the modern civil rights struggle.

That struggle began as a revolt against segregation in public accommodations—buses, lunch counters, libraries, parks. It was aimed at ancient and obsolete institutional arrangements and mores left over from an earlier social order in the South, an order that was being undermined and transformed by economic and technological forces.

As the civil rights movement progressed, winning victory after victory in public accommodations and voting rights, it became increasingly conscious that these victories would not be secure or far-reaching without a radical improvement in the Negro’s socio-economic position. And so the movement reached out of the South into the urban centers of the North and West. It moved from public accommodations to employment, welfare, housing, education—to find a host of problems the nation had let fester for a generation.

But these were not problems that affected the Negro alone or that could be solved easily with the movement’s traditional protest tactics. These injustices were imbedded not in ancient and obsolete institutional arrangements but in the priorities of powerful vested interests, in the direction of public policy, in the allocation of our national resources. Sit-ins could integrate a lunch counter, but massive social investments and imaginative public policies were required to eliminate the deeper inequalities.

Dr. King came to see that this was too big a job for the Negro alone, that it called for an effective coalition with the labor movement.

As King told the AFL-CIO convention in 1961:

Negroes are almost entirely a working people. There are pitifully few Negro millionaires and few Negro employers. Our needs are identical with labor’s needs—decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old-age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community . . . That is why Negroes support labor’s demands and fight laws which curb labor . . . That is why the labor-hater and labor-baiter is virtually always a twin-headed creature spewing anti-Negro epithets from one mouth and anti-labor propaganda from the other mouth . . .

The duality of interest of labor and Negroes makes any crisis which lacerates you a crisis from which we bleed. As we stand on the threshold of the second half of the twentieth century, a crisis confronts us both. Those who in the second half of the nineteenth century could not tolerate organized labor have had a rebirth of power and seek to regain the despotism of that era while retaining the wealth and privileges of the twentieth century . . . The two most dynamic and cohesive liberal forces in the country are the labor movement and the Negro freedom movement . . . I look forward confidently to the day when all who work for a living will be one, with no thought to their separateness as Negroes, Jews, Italians or any other distinctions.

This will be the day when we shall bring into full realization the American dream—a dream yet unfulfilled. A dream of equality of opportunity, of privilege and property widely distributed, a dream of a land where men will not take necessities from the many to give luxuries to the few; a dream of a land where men will not argue that the color of a man’s skin determines the content of his character; a dream of a nation where all our gifts and resources are held not for ourselves alone but as instruments of service for the rest of humanity; the dream of a country where every man will respect the dignity and worth of human personality—that is the dream.

And so, Dr. King went to Memphis to help 1,300 sanitation workers— almost all of them black—to win union recognition, higher wages, and better working conditions. And in the midst of this new phase of his work he was assassinated. Since then, the sanitation workers have won their fight. But the real battle is just beginning.

The Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders is the latest in a series of documents—official, semi-official and unofficial—that have sought to arouse the American people to the great dangers we face and to the price we are likely to pay if we do not multiply our efforts to eradicate poverty and racism. The recent recommendations parallel those urged by civil rights and labor groups over the years. The legislative work of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and of the AFL-CIO has been vital to the progress we have made so far. This work is now proceeding effectively on a broad coordinated basis. It has pinpointed the objectives for which the entire nation must strive.

We have got to provide meaningful work at decent wages for every employable citizen. We must guarantee an adequate income for those unable to work. We must build millions of low-income housing units, tear down the slums and rebuild our cities. We need to build schools, hospitals, mass transit systems. We need to construct new, integrated towns. As President Johnson has said, we need to build a ‘second America’ between now and the year 2000.

It is in the context of this national reconstruction that the socioeconomic fate of the Negro will be determined. Will we build into the second America new, more sophisticated forms of segregation and exploitation or will we create a genuinely open, integrated and democratic society? Will we have a more equitable distribution of economic resources and political power or will we sow the seeds of more misery, unrest and division? Because of men like Martin Luther King, it is unlikely that the American Negro can ever again return to the old order. But it is up to us, the living black and white, to realize Dr. King’s dream.

This means, first of all, to serve notice on the 90th Congress that its cruel indifference to the plight of our cities and of the poor—even after the martyrdom of Dr. King—will not be tolerated by the American people. In an economy as fabulously productive as ours, a balanced budget cannot be the highest virtue and, in any case, it cannot be paid for by the poor.

Next, I believe, we must recognize the magnitude of the threat we face in an election year from a resurgence of the rightwing backlash forces. This threat will reach ever greater proportions if this summer sees massive violence in the cities. The Negro-labor-liberal coalition, whatever differences now exist within and among its constituent forces, must resolve to unite this fall in order to defeat racism and reaction at the polls. Unless we so resolve, we may find ourselves in a decade of vindictive and mean conservative domination.

We owe it to Martin Luther King not to let this happen. We owe it to him to preserve and extend his victories. We owe it to him to fulfill his dreams. We owe it to his memory and to our future.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Bayard Rustin (1912-1987) was a leading proponent of Gandhian nonviolence in the American civil and gay rights movements. To quote from his biography (at kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu), Rustin was a “close advisor to Martin Luther King, Jr. and one of the most influential and effective organizers of the civil rights movement. He organized and led a number of protests in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, including the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. While Rustin’s homosexuality and former affiliation with the Communist Party led some to question the wisdom of working with him, Dr. King recognized the importance of Rustin’s skills and dedication to the movement. In a 1960 letter, King told a colleague, ‘We are thoroughly committed to the method of nonviolence in our struggle and we are convinced that Bayard’s expertness and commitment in this area will be of inestimable value.’” The literature on and by Rustin is extensive. We would highly recommend, John D’Emilio, Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003. An excellent selection of Rustin’s writings, including some of his most significant essays on nonviolence is, Time on Two Crosses: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin, edited by Devon W. Carbado and Donald Weise, San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2003. This essay was first published in Nonviolence after Gandhi: A Study of Martin Luther King Jr., Edited by G. Ramachandran & T. K. Mahadevan, New Delhi: Gandhi Peace Foundation, 1968, and was made available to us by mkgandhi.org under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.