Music and the Psychology of Pacifism: Benjamin Britten’s

War Requiem

by Arthur D. Colman M. D.

Benjamin Britten, c. 1950s; photographer unknown; courtesy of operanews.com

Benjamin Britten is one of the great composers of the twentieth century. He is also one of those rare individuals who was able to live fully and creatively the life he fervently wished for as a child. Musical composition was his desired life; in the spirit of Puccini’s great aria from Tosca, “Vissi d’Arte,” his was a life in art, and art in life.

A child may be filled with desire to express objectively the music that is in his mind, and because music is so demanding an art form it may take years to master even the technical and aesthetic requirements. Finally, though, a composer will be judged on something more than his skill and the beauty of what is created. For Britten to become a great composer, which was his conscious desire, his music would need, in the words of Indian musicologist Anupam Mahajan, to be “a realization of the essence of existence beyond the routine life of man.” (Mahajan 1989, p. 13)

I believe that Britten achieved something of that essence in much of his music. Britten was a composer whose music communicated his deepest moral convictions, his fundamental truths in life. Because these were not consonant with the world around him, his music became the language of a prophet who lived, as prophets often do, on a fragile boundary between the Wilderness and the Ruler’s Court. The compelling beauty of his music made it possible for Britten to navigate this line and be heard by many people who preemptively disagreed with his message. His subjects, so relevant to his own and today’s world, were the subjects of many prophets before him: Violence, Injustice, Innocence Betrayed, the Scapegoat, and most of all, War.

This paper is primarily a contribution to Jung’s psychology of individuation. As we shall see, Britten was an individual whose powerful sexual and political preferences were overwhelmingly antagonistic to the consciousness of the collective in which he lived and worked. Britten’s individuation was inextricably bound with changing that consciousness, and musical composition was the transformative element that he used as a “third thing” (Montero and Colman 2000, p. 218) to simultaneously change world and self — the work of individuation. Britten’s War Requiem is a work of great beauty and power; it is also the ripe fruit of his individuation process — an interpretation, offering, and challenge to institutions and nations committed to violence.

What first connected me to Britten’s music was my own work in awakening the consciousness of the collective to the problem of scapegoating. (Colman 1995) Great art must reflect the culture with a mirror whose image unsettles, inspires, and ultimately transforms. Britten’s musical oeuvre, especially his War Requiem, is a potent communication to his species about the great scourge of War. It is probably easier to see such an interpretative praxis in those whose work is political or ideological. I hope, however, to show how Britten’s personal and creative development led to music that could evoke a collective emotional and intellectual response strong enough to manifest his desire to transform the world around him. The War Requiem is Britten’s Satyagraha; his “I have a dream” speech.

Britten’s World

Benjamin Britten was born in Lowestoft, England, a coastal town on the North Sea in 1913; he lived much of his life in Aldeburgh, about sixty miles south, and he died there in 1976. His father was an oral surgeon who built up a substantial practice. His adoring mother was a housewife and mother of four with a strong interest in music. She was, according to her son, Benjamin, youngest and most musically talented of the four, “a keen amateur with a sweet voice.”

There were of course skeletons in the family closet and in Benjamin’s developmental history. But accounts of his childhood are positive and enthusiastic. He was the proverbial happy child: physically adorable, bright and musically precocious, with loving and protective parents and mostly adoring older siblings. Occasionally he had to fight for the piano with his older brother Robert, who usually gave way, and he was not allowed to compose all the time by his mother, as he would have liked. At school he excelled at mathematics and was a decent athlete. He may have faced mild corporal punishment, perhaps sexual play and, in one highly speculative report, sexual harassment by a teacher. (Carpenter 1992, p. 557) What Britten remembered most, however, was the school music teacher who was pretentious and unhelpful, not willing or suited to enlist his student’s extraordinary talent. His parents made up for this lack by hiring Frank Bridge, one of England’s preeminent musicians and composers, to further their son’s musical education. Bridge, who had no other pupils, agreed to take Britten on upon hearing the thirteen-year-old’s compositions. Reading about Britten’s childhood, I was struck by the essential goodness of it all. All of his teachers, friends, and even enemies invoke phrases like “golden boy,” “good boy,” “best boy,” “great little man,” “The Best Brought-Up Little Boy You Could Imagine” to describe him. (Idem)

His golden, innocent childhood, and his well-mannered, soft-spoken persona, did not match his music. Leonard Bernstein said Britten “…was a man at odds with the world. It’s strange because on the surface his music is decorative, positive, charming and it’s so much more than that. When you hear his music, really hear it, not just listen to it, you become aware of something very dark, gears that are grinding and not quite meshing. And they make a great pain. His was a lonely time. Yes, he was at odds with the world in many ways and he didn’t show it.” (Bernstein 1980, video 1158)

But the traditional scenario of childhood trauma writ large in his creative outpourings needs to be turned on its head. Bernstein touches on what seems to me to be the critical point: Britten was at odds with his world. The sweet innocence of his childhood is at dramatic odds with the collective psyche of the world in which he lived, and betrayed innocence is a major theme in his work. His world made him even a potential criminal because of his homosexual preference and his passionate commitment to pacifism. It also was a world that he saw as murdering his friends and peers in wars that he viewed as created by fathers, not sons, another prominent theme. The twentieth century was a psychotic time of unprecedented mass barbarity, which changed and should have changed the definition of sanity in conscious societies. Britten’s artistry lies in the psychological and artistic forces that flowed through his music as he reflected upon and interpreted the darkest parts of his era. Ultimately his creative gift attracted listeners who might have otherwise shunned and denigrated him for his lifestyle and ethos.

Britten always wanted to be a composer, and the security he felt about composing ran very deep. He was extremely vulnerable to criticism; this was an extension of the life theme of betrayal (as if he couldn’t abide the disparate messages from inner and outer world). As a child, and certainly as a mature composer, he was increasingly able to establish self-referential standards for his music. But to do this he required a sheltered world, one in which there was stability and support from like-minded colleagues. And this central need required wrestling with his homosexuality and his pacifism.

Britten probably did not fully accept the need to live out his sexual orientation until the beginning of his lifelong partnership with Peter Pears in late 1939, when he was twenty-four years old. Before that, he passively resisted actualizing his sexual orientation despite considerable self-knowledge and the powerful urgings of friends who knew him all too well. After studying composition at the Royal College of Music, Britten had found an intellectual home with other artists — left wing, many gay, and some pacifist – in the theatre and in the government-funded GBO Film Unit. This provided a decent livelihood and a chance to expand his skills in programmatic compositions around political and social themes. The most significant influence was the powerful psycho-political effect of the worldly W. H. Auden and his radical circle.

In an early letter, Auden writes: “For my friend Benjamin Britten, composer, I beg that fortune send him a passionate affair.” (Auden quoted in Carpenter 1992, p. 91) Later a poem, written to and for Britten, continued this theme:

Underneath the abject willow,

Lover, sulk no more;

Act from thought should quickly follow:

What is thinking for?

Your unique and moping station

Proves you cold;

Stand up and fold

Your map of desolation. (Auden 1936/1977. p. 160)

At stake, for the bossy, brilliant poet, was his friend’s capacity for passion, without which he felt Britten’s compositions would never fully emerge. Even after Britten and Pears became a couple, an Auden letter to him was still concerned about “the dangers that beset you as a man and as an artist. If you are really to develop to your full stature, you will have. I think, to suffer and make others suffer, in ways which are totally strange to you at present, and against every conscious value that you have, i.e., you will have to be able to say what you never yet have had the right to say.” (Mitchell and Reed. Vol. 2, 1991, p. 1016)

Auden’s words were both warning and prophesy, for Britten’s essential innocence and goodness was deeply challenged by the world around him. And as “a good boy,” he had to transgress to compose and to live. According to Pears and his closest friends, Britten never fully accepted his own sexual orientation even as he lived it. (Pears 1980, video 1158) But the fact of his homosexuality, illegal in his country, was also the lifelong prod that kept Britten and his talents from folding into the golden, middle-class security that he understood so well. Homosexuality’s pervasive influence on his feelings, including his feelings of acceptance in the public arena, forced him towards a lifelong moral exploration of such themes as the role of the outsider, that of the betrayer of innocence, the psychology of disgrace, and the plight of the innocent victim. Much of his music ruthlessly examined the collective psychology of the scapegoat and the trauma for the individual who is put in that position.

The other disjunction between Britten and the surrounding society was his fervent belief in pacifism. Whereas homosexuality was not a subject that Britten dealt centrally with in his music (except rather chastely in his final opera, Death in Venice), his views about war and violence were always at the forefront of his work. Pacifism in Britain was a popular cause among young intellectuals in the 1930s. World War I had exacted a terrible toll from British youth, and now the country was talking of rearming. With the violent patriarchy at it again, the young artists and writers wanted to fashion their own social vision. Britten was swept up in this social movement, although his profound anti-violent convictions certainly predated it. He declined to take part in his school’s popular officers training program, and he wrote an impassioned essay indicting hunting and cruelty to animals, for which he was awarded no marks. His most influential teacher and mentor, Frank Bridge, pursued his own pacifist views in frequent conversations with Britten. What is extremely clear is that Britten’s abhorrence of both public and private violence was a powerful motivator in his compositions, and that abhorrence guided rather than followed his musical outpourings. If Britten’s homosexuality provided an underlying, if ambivalent, identification with the outsider and the scapegoat, pacifism, with its deep-rooted insistence on the disavowal of all violence, became a fully realized obsession.

Largely because of his views about the coming war, Britten, together with his at that time still platonic friend Pears, followed Auden and Isherwood (the former an avowed pacifist) to the United States in 1939. In the face of the Nazi threat, turning one’s back on an England poised for war was an extremely unpopular act. Britten’s musical life certainly gained from his exposure to American musicians. He renewed his friendship with Aaron Copland, whom he had known in London, and he met Boston Symphony Conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who commissioned several of his pieces, including the opera Peter Grimes. But he was also shunned by many of his countrymen even as his music was attracting notice. Musical critics in London abused him for his pacifist stance and “cowardly” self-exile, while grudgingly praising some of his new compositions.

Britten and Pears also felt a deep homesickness for their country. Confronted with actual war — begun by German invasions in central Europe and helped along by Britain’s diplomatic acquiescence there — the young men were humiliated to be forsaking England in such a time of need. In 1942, Britten and Pears returned home. By then, German U-boats were patrolling the Atlantic, and embassy officials discouraged the trip. They would also have to petition, and be examined by, a formal tribunal to be granted conscientious objector status; otherwise, they would go to prison. Nevertheless, against the advice of many friends and supporters, they came home.

Music in a Moral Key

Excerpts from Britten’s statement to the War Board give us a picture of his convictions at twenty-nine years old:

The whole of my life has been devoted to acts of creation (being by profession a composer) and I cannot take part in acts of destruction. (Mitchell and Reed, Vol. 2, 1991, p. 1046)

I do not believe in the Divinity of Christ, but I think his teaching is sound and his example should be followed. (Idem, fn.)

After some complications, his rather tortuous explanation of these religious beliefs led to full Conscientious Objector status.

The man who returned to England had learned a great deal about the power of the collective to affect his life. He also had learned how his musical talent could be used as a weapon, for there was little doubt that officials saw his increasingly recognized talent as a composer as valuable to a nation gripped by war.

Britten was already at work on the opera Peter Grimes. Grimes, a fisherman living in the small coastal village of Borough, was accused of abusing and killing his young apprentice boys by a community more hostile to his aberrant ways than his possible crime. Britten’s portrait of the individual victim and the collective scapegoat is musically powerful and chilling:

Who holds himself apart, lets his pride rise.

Him who despises us we’ll destroy.

And cruelly becomes the enterprise.

Britten himself chose to live most of his adult life in Aldeburgh, an isolated fishing town on the forbidding North Sea. There he separated himself from the musical and artistic community in London. There was a canny self-knowledge in this decision. In Aldeburgh, Britten and Pears created a working collective that would nurture both for the rest of their lives. Britten knew that composing would require a special psychological environment, one that offered nurturance, not conflict; harmony, not diversity; inclusion, not intrusion or exclusion. In time he gathered around him people who could help him create and would not criticize his lifestyle or his values. Many were gay men with similar pacifist views. First among them was Peter Pears, who became his life partner and musical colleague. For Pears, Britten wrote all of his leading tenor vocal parts. Britten limited his ties with the great opera companies and musical artists and impresarios in London and instead created his own creative coterie, his own opera and musical companies, his own concert hall, and eventually his own music festival at Aldeburgh.

Perhaps most telling was his successful effort “not to hold himself apart” from the non-artists in the community in which he lived. He sought and obtained the involvement of the towns people of Aldeburgh in every aspect of his work, using their chorus, and creating a children’s chorus, using locals for their administrative and construction skills, using churches, town hall, and empty mills for his performances. He often composed for the community talent and community audiences and virtually created a new vocal form, the Chamber Opera, to fit local musical resources. The prestigious Sadler’s Wells and other London companies and players were included only in so far as they worked for him and in his world.

This psychological orientation should not be reduced to a paranoid escape or regressive return to a doting family: rather it was a creative alloplastic solution to an inner dilemma, a way to reshape the world to match his vulnerabilities and his way of life. And because of his great talent, moral intent, and intense work and love relationship with Pears, it succeeded. Britten drew the musical talent that he needed to Aldeburgh. He organized his life in order to compose music, and from that secure but liminal space, the music he composed became a series of moral interpretations to the larger world.

The Power of Music to Heal

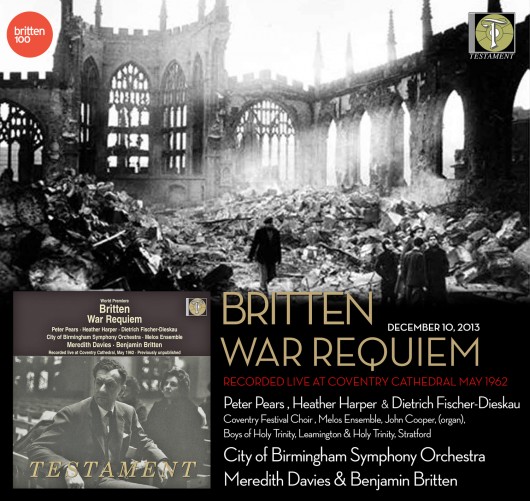

Coventry Cathedral 2013 poster; artist unknown; courtesy of hm-distribution.com/

Almost twenty years passed before Britten wrote his War Requiem, finished December 20, 1961, and first performed in Coventry on May 30, 1962. During those twenty years, Britten composed the major body of his work.

Since the 1940s he had wanted to compose a major choral orchestral piece — the standard of which, at least in the Western musical tradition, is the Mass and particularly the Requiem Mass. Characteristically, Britten wanted to write on a pacifist theme. He had earlier written an oratorio, Mea Culpa, in response to the dropping of the atomic bomb, and had already thought of composing a Requiem in response to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. In 1962, the committee overseeing the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral, demolished by the Luftwaffe, asked Britten to write and conduct a new work to mark the re-consecration.

There is little doubt that Britten’s “God” was not a traditional one: we already know his thoughts about a supernatural God from his remarks to the Conscientious Objector Tribunal. And his preparation ensured that the War Requiem would be a vehicle for a theme of greater importance to Britten than religion. His aim in this piece is first and foremost to deliver an interpretation to the world about the pain and betrayal of a century and the complicity of nations, religious institutions and ourselves in the loss of life and hope that ensued. “A call for peace” is what the Russian soprano Galina Vishneskaya said Britten called it. (Vishneskaya in Cooke 1996, p. 26) We can find this wish expressed in every part of the Requiem. With obvious symbolism, the composer planned to write solos for soprano, baritone and tenor singers from three different countries: Pears was his choice for British Tenor, the great Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau was the German Baritone, and Vishneskaya was to be the Russian Soprano. Vishneskaya was not allowed by her government to sing at the opening, however, an ominous and prophetic sign of the growing “cold” war.

Britten’s choices were undoubtedly formed by knowledge of the kind of voices he wanted. But the internationalism of them was also a simple and profound attempt to heal Europe’s wounds, characteristic of his use of every element of the composition and presentation of the Requiem to serve the larger moral intent.

Elements of Composition

Baudelaire once wrote that, “music cannot pride itself on being able to translate all or anything with precision, as can painting or writing. But music translates in its own way and using means, which are proper to it. In music…there is always a lacuna which is filled in by the listener’s imagination.” (Baudelaire 1861/1964, p. 113) Richard Wagner said, “Where the speech of humankind leaves off, there the art of music commences.” (Wagner in Fisk 1997, p. ix)

Most composers, including Britten, tend to begin their composition with nonmusical elements, especially when there is a programmatic requirement, as in an opera, or a structural requirement, as in a Mass. In preparing a libretto for the War Requiem, Britten pruned and edited Wilfred Owen’s poems with great care, and struggled to interdigitate their lines and phrases with words from the Missa pro defunct, the Requiem Mass. He diagrammed a variety of structures that he would use to configure and integrate words, music, choruses, and orchestras. The way he found the music he poured into the nonmusical structures cannot be reduced or psychologized, and for that, his listeners can only be thankful.

Britten uses a very specific musical device, the tritone, as musical and ideological center of the work. This tritone interval, also known as the augmented fourth or diminished fifth, is the interval between the first and third successive whole tones in any scale: for example, the interval F-B, or C-F# (the first two notes of Bernstein’s song “Maria” from West Side Story). This interval has long represented an “outcast” tone or “scapegoat” sound in the musical palette. The tritone was known as diabolus in musica and was actually banned from use in church music during the Middle Ages. Church leaders found it to be unsuitable for Christian worship. Of course this “banned interval” also became a mythic shadow tone which was very attractive to dissenters! It was rumored to be used in “Black Sabbaths,” midnight masses, and other “unnatural rites.” Although daring composers gradually began to use it in secular works, the tritone still retains its aura of shadow.

Britten based much of the musical composition of his Requiem upon the tritone. It may seem strange that a simple vibrational interval can successfully hold the emotional center of the work, but the very imprecision of musical elements and the primitive emotionality of the language of sound are also the source of its power. The juxtaposition of tritone and poetry mocks the message of the Mass: liberation from death through Christ, and the inevitability of rebirth for the faithful. The Mass itself is a targeted symbol of Britten’s pacifist attack on the culture of war: our dependency on religion, our unreflective acceptance and comfort in venerable tradition, he implies, are all powerfully connected to our acquiescence to War. The tritone echoes through Britten’s composition like Chagall’s ghostly fiddler swooping over a gigantic graveyard of soldiers.

Owen and Britten in Duet

Wilfred Owen was considered to be one of the great poets of World War I, and it is to his poetry that Britten turned for his harsh words on war. Of strong pacifist beliefs, Owen still felt obliged to enlist in the British Army in a unit that was called “The Artists’ Rifles.” He was hospitalized for shell shock and neurasthenia in Edinburgh, where he met and was influenced by the poet Siegfried Sassoon, who was also a patient. Owen returned to the front and wrote war poetry from the foxholes. Seven days before the Armistice on November 11, 1918, he was extremely despondent, and was then killed in action leading his troops across the Sambre Canal near Ors in Northeast France. He was twenty-five.

Owen was a psychologically inspired choice, and not just for his poetry; he was an artist hero untainted by the questions of cowardice heaped on Britten during his exile in America. Owen is therefore Britten’s soldier as well as his muse in delivering the message. In the title page of his score, Britten pays Owen special homage by quoting his famous preface (to a proposed compilation of poems) written shortly before his death:

Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity… All a poet can do today is warn. (Britten 1962, frontispiece)

Britten’s central concern in his Requiem was also War; War and the victims of War. He wanted the largest possible context for this pacifist work, and he wanted a hand in destroying, or at least subverting, the institutions that preserved war. He chose the Church and its great musical form to represent all the sanctified institutions which allow the Nations to send sons off to die. To do this, he went directly to the heart of the beast and challenged Christianity’s ancient and sacred celebration of life after death: the Mass for the Dead.

The Promise of Death

The centerpiece of the War Requiem is the Offertorium, which contains the ancient promise of Abraham:

Sed signifier sanctus Michael

Repraesentet eas in lucem sanctem:

Quam olim Abraham promisisti

Et semini ejus.

But let the standard-bearer, Saint Michael

Bring them into the holy light:

Which, of old, Thou didst promise

Unto Abraham and his seed.

Quam olim Abraham promisisti, the promise of Abraham, that ancient connection, is a moment of great power. Long ago it was foretold and it has now come to pass in Christ — that is the affirming message regarding Abraham’s prophesies. Christianity has always been concerned with finding validation, whether from miracles or Saints or from the confirmation of prophesies contained in the Old Testament. Musically, this text of the Mass is often set in a fugue, a Renaissance music form perfected by Bach that multiplies and deepens the power of words through a complex interweaving of theme and variations. This music is almost always joyous. In Mozart’s Requiem, it is a triumphant choral dance; Verdi sets it in a gorgeous operatic aria for baritone.

Britten has other ideas. The music begins with the boys’ chorus in an almost mournful, monotonic chant, which becomes faintly pleading as it continues. This chorus represents the purity and innocence of youth, a prayer for the deliverance of the souls of the faithful “from hell, from darkness.” The children’s voices are broken into by the adult chorus singing quam olim Abraham promisisti to a theme incorporating the now familiar tritone. The musical line here is jaunty and irreverent, yet tension filled and increasingly discordant, carrying a hint of promise, perhaps a broken promise from God given in a former time. The effect is both ironic and confused; the hope of deliverance undercut and questioned. This section ends in a confident segue to another Owen poem, the content of which answers the musical question in no uncertain terms.

Owen’s poem retells the familiar Abraham and Isaac story, which gave the basis of the promise itself. Owen’s retelling uses the Sumerian name Abram, signifying a younger, less-developed man than the later Abraham. Britten captures the pious young man’s spirit in a musical line infused with the jaunty, sadistic clarity of a narcissist intent on a single, unmodifiable course. There is no love, no hesitation in either word or music as the sacrifice is described:

So Abram rose and clave the wood, and went,

And took the fire with him and a knife.

Isaac, the scapegoat, is not as sanguine as his father. He questions Abram about the absence of the sacrificial lamb. His tenor musical line is suddenly gorgeous, lush but emanating an innocent and pathetic plea from trusting son to trusted father:

My Father, Behold the preparations, fire and iron,

But where the lamb for this burnt-offering?

The music turns dark as the narrator answers in a dark recitative:

Then Abram bound the youth with belts and straps,

And builded parapets and trenches there,

and stretched forth the knife to slay his son.

The anachronistic words connote WW I technology as well as the frank sadomasochistic pleasures implied in the tools of sexual bondage; militant music brings us into the horrible present tense of trenches full of human sacrifice, including Owen himself. We are now in the space of War and its perversions, ready for the worst. But Britten allows a brief dramatic return to an earlier, more trusting, consciousness. The Lord, sung as a sweet duet in a major third between tenor and baritone, stays the father’s hand and points out the Ram caught in a thicket by its horns:

Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

And then the famous chilling lines sung in trenchant narration which speaks to the terror of sacrificial sons everywhere:

But the old man would not so,

but slew his son -

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.

These words, a dramatic deviation from all Abraham and Isaac stories before it, are shocking. Almost immediately the music and words disintegrate into an eerie trilogue among soloists, choruses and orchestra using the quam olim theme in weak and rhythmically disintegrating, fragmented lines: “half the seed” … “one by one.” The boys’ chorus begins mournful completion of the Latin liturgy now ironically transforming “prayer and praise” to the inevitable sacrifice as future soldiers:

Hostias et preces tibi

Domine Laudis offerimus:

We offer unto thee, O Lord,

Sacrifices of prayer and praise

The adult chorus once again takes up the fugue of promise, now a hypocritical and shameful boast: “Quam Olim Abraham Promisisti,” the promise of annihilation.

Britten has achieved, in effect, an extraordinary choreography of Owen’s poetry with Latin text, tenor and bass solo voices, adult and boys’ chorus and symphonic and chamber orchestra. He had written nine operas by the time he composed the War Requiem, and the experience served him well. Owen’s great text and its horrifying counterpoint of the adult chorus (we: the collective, the guilty?) and the boys (the innocents, the fatherless, the scapegoats?) inspire and contain what Britten creates. The boys pray and mourn, Isaacs pleads, but the Father Abram cannot stay his hand, and there is no counterforce to his desire for slaughter. God’s six thousand year promise of protection is here transformed into a calculated betrayal by Elders seeking power and potency, and the betrayal is laid out in an unforgettable and unforgiving way. The hope for eternal life that religion offers both ritually and emotionally, through rebirth and renewal, the promise of God, that venerable covenant upon which Judeo-Christian civilization is based, is relegated to the darkest abattoirs of human history.

The Question of Consolation

What, then, of the feminine in Britten’s Requiem, of age and wisdom, of mercy and succor, of love? Although the text of the Missa pro defunctis itself brings no feminine figure or story to its liturgy, in practice there are often songs of a suffering and consoling Mary interpolated into the service. In the War Requiem, this kind of feminine voice is certainly not present in Britten’s chosen texts or in most of the solo soprano singing parts. There is, for instance, no Mezzo represented. Although in the next movement, the Sanctus, a traditional hymn of faith, the soprano is given a major role, Britten has transformed her solo into the most desolate music in his Requiem. He introduces her lines with devilishly insistent bells, a mix of odd percussive sounds from vibraphone, glockenspiel, antique cymbals, and piano:

Sanctus, sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth.

Holy Holy Holy. Lord of God of Sabaoth.

The music is jagged, harmonies and scales change quickly, and the tritone is prominent, making her song of faith fierce and judgmental (compared, for example, with Mozart’s joyous cosmic dance of the same text). The soprano returns with a mournful Benedictus sung on words that should symbolize salvation and eternal life.

Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the lord.

Help from the feminine gone, Britten uses Owen’s words against any hope from the Elders or Earth:

Age?

When I do ask white Age he saith not so:

‘My head hangs weighted with snow.’

And when I hearken to the Earth, she saith:

‘My fiery heart shrinks, aching.

It is death.

Mine ancient scars shall not be glorified,

Nor my titanic tears, the sea, be dried.’

In the Agnus Dei, the penultimate movement of the Requiem, Britten shifts to a more somber mood. The Latin text requires it: glory and exultation in the Lord’s coming gives way to the more earthly role of a forgiving God who must help a struggling humanity:

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem

Lamb of God who taketh away the sins of the world, give us rest.

The tenor is center stage with a sad and beautiful song which is still undercut by Owen’s brutal words:

And in their faces there is pride

That they were flesh-marked by the Beast

By whom the gentle Christ’s denied…

And:

The scribes on all the people shove

And bawl allegiance to the state.

The “gentle Christ” is clearly present in the music and in the dynamics of its presentation. The tritone, C-F#, is still a dominant force, but Britten softens its dissonance by harmonizing the F# in B minor and the C in C major, in alternate measures. Britten ends this section by uncharacteristically deviating from the standard Missa pro defunctis liturgy and adding a familiar refrain, which musically hints at resolution in C minor:

Dona nobis pacem

Give us peace…

It is as if, having deconstructed so much of Religion with the more powerful and morally devastating machines of War, Britten takes a musical breath … and wonders where he is going. What does he want to say to a 1960s Cold War audience, representatives of a society that has been overwhelmed by violence, death, and loss and now is starting to rebuild its Churches and its War machines? Can he deny the Christian message that is his heritage, the sins of the world taken away by a gentle God? Can he persist in making that most subtle and devastating interpretation of all, that mankind will not change its warlike behavior as long as it is under the spell of the doctrine of rebirth and the promise of life after death, which the Catholic Mass (among other of Religion’s rituals) explicitly offers? Britten pauses before the final movement and considers all this: “Give us peace!” he interpolates, but how? Despite the beauty of these ancient lines, there is still War looming behind and ahead with no hint of resolution.

War Is Death without Rebirth

His answer comes quickly and it is no surprise. The final movement Libera Me begins with the roll of drums, military drums, and crying voices, which, though in Latin, can only be specters of dead soldiers. We are back on the battlefield, the place of death, the place where, for Britten at least, all questions about peace must be answered. The Latin text begins with an ultimate prayer in this regard:

Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna.

Deliver me, O Lord, from death eternal.

The music moves from plea to a glimpse of the hell that is war, the drums again, the crack of whips, the words from the Mass that remind us of the real fire that killed these boys called soldiers:

Dum veneris judicare saeculum per ignem

When thou shall judge the world by fire

We hear echoes from a ghostly battlefield, a place with no answers and no God. And suddenly, out of dregs of that dark epiphany, a human voice begins to sing the last and most famous Owen setting, “Strange Meeting.” The poem portrays two soldiers from opposing sides meeting on the battlefield. The first soldier, understanding nothing of his real situation, sings in familiar tritone the agonizing irony of denial. ‘Strange friend,’ I said, ‘here is no cause to mourn.’

In this entreaty we meet, as Britten desires for us to do, our own selves and the world in denial, a world in which war is still a possibility even after World War II, the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Vietnam, and beyond… The “friend” answers:

‘None,’ said the other, ‘save the undone years,

The hopelessness. Whatever hope is yours

Was my life also: I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world.

For by my glee might many men have laughed;

And of my weeping something had been left,

Which must die now. I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.’

Britten frames these wrenching sentiments in spare musical lines, often unaccompanied, beginning with the ominous tritone and gradually adding other intervals, then lyric lines and harmonies from other Britten anti-war pieces. There is sadness and also despair as if there is no more to be played or sung. But there is more sadness when we learn that this duet is between killer and killed:

I am the enemy you killed, my friend

I knew you in this dark…

The two enemies now both know they are dead. Deadly enmity fueled by national causes and other irrationalities make no difference. “Let us sleep now,” says one, and a duet of the soloists ensues on these sad, life-empty lines.

A Requiem Mass usually ends on a positive note, so a religious reprieve in the last bar lines is still possible. But we already know Britten will not offer this false hope. For these soldiers in the foxholes, sleep is but a brief respite from the finality of death; there is no step into eternal life on that killing field. The male soloists continue to sing “let us sleep now” while the boys’ chorus and then the adult chorus begin the Latin burial text:

In paradisum deducant te angeli

May the angels escort you to heaven

Whatever hope is held in this beautiful ensemble is abruptly stopped by mournful bells and a long silent rest. Twice more, the ensemble begins and is stopped mid phrase by the bells. Reluctantly, then more firmly, the adult choir starts to intone the requiem aeternam, the tritone-based chant from the first movement. Now the original words of hope:

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine

Rest eternal grant unto them, O lord?

are replaced by a new text:

Requiescant in pace. Amen

May they rest in peace. Amen

The last musical notes of the piece, however, are the familiar tritone interval resolving to an F major chord, creating a question. Musically, emotionally, spiritually, and existentially we are left unsettled, unresolved, our longings for any kind of lasting peace unsated except for Britten’s warning message to the world about War: a great composer, who spoke from the edge, the place of victims and prophets, interpreting his truth to all of us.

References:

References to a specific music text, Latin text, and poetry (excerpted from the work of Owen) are taken from the full orchestral score of Britten’s War Requiem (London: Boosey and Hawkes, 1962). Music selections referred to in the text of this paper can be heard on CD 414383-2 War Requiem, Opus 66 (London: Decca Records, 1963, 1985), and other recordings.

Auden, W. H. (1936/1977). “Poems 1931-1936, XXX (For Benjamin Britten)”, in Mendelson, E. (Ed.), The English Auden. London: Faber and Faber.

Baudelaire, C. (1964), “Richard Wagner and Tannhauser in Paris” in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays. London: Phaidon.

Britten, B. (1962). War Requiem, Op. 66. London: Boosey and Hawkes.

Carpenter, H. (1992). Benjamin Britten: A Biography. New York: Scribner.

Colman, A. D. (1995). Up from Scapegoating: Awakening Consciousness in Groups. Evanston, IL: Chiron.

Cooke, M. (1996). Britten, War Requiem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mahajan, A. (1989). Ragas in Indian Classical Music. New Delhi: Gian.

Mitchell, D. and Reed, P., eds. (1991). Letters from a Life: Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Montero, P. and Colman, A. D. (2000). “Collective Consciousness and the Psychology of Human Interconnectedness,” Group. Vol. 24, Nos. 2/3.

A Time There Was … A Profile of Benjamin Britten (1980). Video 1158, Kultur.

Wagner, R., in Fisk, J., ed. (1997). Composers on Music. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

I wish to thank for their help: Bryan Baker PhD, and Dr. Carl Johengen. (ADC)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Arthur D. Colman M.D. is a practicing psychiatrist who received his training at Harvard College and Medical School, and U.C. Medical Center, San Francisco where he is also Clinical Professor at the Department of Psychiatry. He has further trained at the C.G. Jung Institute in San Francisco. As stated on his site Dr. Colman is “the author of 9 books on the human life cycle, healing, and scapegoating, and has contributed to many books, professional journals and popular publications on these and other subjects including ecstatic relationships, group consultation, leadership, the psychology of war, and the psychological aspects of music compositions and musical composers.” He has received numerous awards and grants, including Fellowships at the National Science Foundation, American Psychiatric Association, and the A. K. Rice Institute where he was also past president. Please consult his website for further biographical and bibliographic information; article courtesy of Dr. Colman.