History of U.S. War Tax Resistance

by War Resisters League

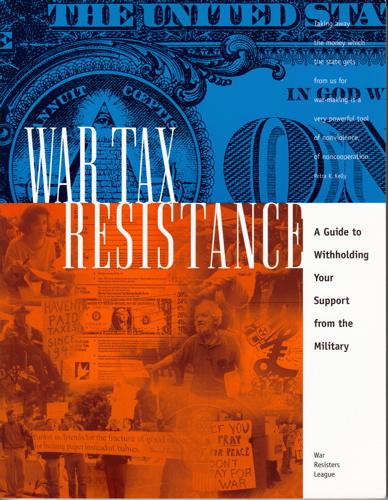

Dustwrapper art courtesy www.warresisters.org

Refusing to pay taxes for war is probably as old as the first taxes levied for warfare. We offer below a summary of such protest, which is to say it does not include other forms of tax refusal and resistance, a common tactic in worldwide labor movements, for example, or in various anti-colonial protests including such well-known examples as the Boston Tea Party.

Indeed, until World War II, war tax resistance in the U.S. manifested itself primarily among members of the historic peace churches — Quakers, Mennonites, and Brethren — and usually only during times of war. There have been instances of people refusing to pay taxes for war in virtually every American war, but it was not until World War II and the establishment of a permanent, centralized U.S. military (symbolized by the building of the Pentagon) that the modern war tax resistance movement was born.

Colonial America

One of the earliest known instances of war tax refusal took place in 1637 when the relatively peaceable Algonquin Indians opposed taxation by the Dutch to help improve their local Fort Amsterdam. Shortly after the Quakers arrived in America (1656) there were a number of individual instances of war tax resistance. For example, in 1709 the Quaker Assembly refused a request of £4000 for a military expedition into Canada, replying, “It is contrary to our religious principles to hire men to kill one another.”

During the French and Indian War (1755) John Woolman inspired many of his fellow Quakers to question and refuse the payment of taxes to pay for the War. In 1755, Woolman addressed the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting with his concern, “Some of our members, who are officers in civil government, are, in one case or other, called upon in their respective stations to assist in things relative to the wars; but being in doubt whether to act or crave to be excused from their office, if they see their brethren united in the payment of a tax to carry on the said wars, may think their case not much different, and so might quench the tender movings of the Holy Spirit in their minds. Thus, by small degrees, we might approach so near to fighting that the distinction would be little else than the name of a peaceable people.”

A group of Woolman’s Quaker friends, including John Churchman and Anthony Benezet, sent a letter to other Quaker meetings: “Being painfully apprehensive that the large sum granted by the late Act of Assembly for the King’s use is principally intended for purposes inconsistent with our peaceable testimony, we therefore think that as we cannot be concerned in wars and fighting, so neither ought we to contribute thereto by paying the tax directed by the said Act, though suffering be the consequence of our refusal, which we hope to be enabled to bear with patience.”

[See also David Gross’s compilation of Woolman’s tax resistance writings, posted here.]

American Revolutionary War (1775–1783)

Just prior to and during the American Revolution, most Quakers were opposed to taxes designated specifically for military purposes, and the official position of the Society of Friends was against any payment of war taxes. Property was seized and auctioned, and many Quakers were jailed for their war tax resistance. Up to 500 Quakers were disowned for paying war taxes or joining the army. Following the war many Quakers continued to refuse because these taxes were being used to pay the war debt, and therefore were essentially war taxes.

The Mexican-American War (1846-48)

The Quakers reacted strongly to the Mexican-American War, because of the wholesale slaughter and the threatened spread of slavery posed by adding more slave-owning territories to the contiguous states. Support for the war, for example, was highest among the slave-owning southern states. Many, again, refused to pay war taxes. However, the most famous instance of war tax resistance was that of Henry David Thoreau. Although not a pacifist he was opposed to slavery, and the imperialist and unjust nature of the war. His refusal to pay the Massachusetts poll tax levied for the war resulted in a night in jail. This whole experience was recorded in his famous essay, first titled upon its publication in 1849 “Resistance to Civil Government” and in later publications by its now more familiar name, “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience.” For a work of its length (28 pp.) it can be argued to have had more influence worldwide than any other single text on tax resistance.

World War II (1939-1945)

Until World War II the individual income tax was a minor part of the federal government receipts (affecting no more than 3 percent of the population). However with the introduction of the employee withholding tax in 1943, for the first time a large percentage of the population was subject to the income tax. The unprecedented amount of money being raised and spent for World War II suddenly touched the consciousness of many pacifists, who up until the war were not required to pay taxes.

In 1942 Ernest Bromley refused payment of $7.09 for a “defense tax stamp” required for all cars, and thus became the first known war tax resister in the modern era. He was arrested and eventually jailed for 60 days. Though Bromley and a few other pacifists did not pay income taxes during World War II, there was per se no movement of war tax refusal.

Post World War II

In April of 1948 the conference “More Disciplined and Revolutionary Pacifist Activity” was held in Chicago, attended by over 300 people. The “Call to the Conference” (signed by A.J. Muste, Dave Dellinger, Harrop Freeman, George Houser, Dwight Macdonald, Ernest Bromley, and Marion Bromley, among others) expressed a need for a more revolutionary pacifist strategy and tactics. Out of this conference grew a new organization, calling itself the Peacemakers. Their newsletter was titled Peacemaker. About forty people who attended the conference stated their intention to refuse part or all of their federal income taxes, forming a Tax Refusal Committee.

This Committee began almost immediately to publish news bulletins, independent of the Peacemaker group. The bulletins were instrumental in engendering concern and giving information on tax refusal. War tax refusal succeeded in achieving nationwide publicity with the issue, in 1949, of a Peacemaker press release titled, “Forty-one Refuse to Pay Income Tax.” For almost twenty years Peacemakers was virtually the only consistent source of information and support for war tax resisters. The Catholic Worker Newspaper, The Progressive, Fellowship, and a few other movement newsletters and magazines, printed sympathetic articles on war tax resistance.

Following World War II and up to the start of the Vietnam War only six people were imprisoned for war tax resistance: James Otsuka, Maurice McCrackin, Juanita Nelson, Eroseanna Robinson, Walter Gormly, and Arthur Evans. All had been found in contempt of court for refusing to cooperate in one way or another with the proceedings.

In 1963 the Peacemakers published the first handbook on war tax resistance, appropriately titled Handbook on Nonpayment of War Taxes.

Vietnam War (1955-1975)

The U.S. Vietnam War was one period in a series of wars commonly referred to as the First and Second Indochina Wars (1946-1975) waged first by the French and then the U.S. We refer here to the Second Indochina War period, more commonly called The Vietnam War (1955-1975).

War tax resistance gained nationwide publicity during the Vietnam War when Joan Baez announced in 1964 her refusal to pay 60 percent of her 1963 income taxes as a protest against the war in Vietnam. In 1965 the Peacemakers formed the “No Tax for War in Vietnam Committee,” obtaining signers to the pledge that, “I am not going to pay taxes on 1964 income.” 500 people were to sign the pledge.

Then several events in the mid to late 1960s occurred making this a pivotal period for the war resistance movement, signaling a shift in war tax resistance from a couple of hundred to eventually tens of thousands of refusers.

A committee led by A.J. Muste obtained 370 signatures (including Joan Baez, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, David Dellinger, Dorothy Day, Noam Chomsky, Nobel Prize winner Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, publisher Lyle Stuart, and Staughton Lynd) for an ad in The Washington Post, which proclaimed their intention not to pay all or part of their 1965 income taxes.

A suggestion in 1966 to form a mass movement around the refusal to pay the (at that time) 10 percent federal telephone excise tax was given an initial boost by Chicago tax resister Karl Meyer. This was followed by the War Resisters League (WRL) developing a national campaign in the late 1960s to encourage refusal to pay the telephone tax.

In 1967, Gerald Walker, an editor of The New York Times Magazine began the organizing of Writers and Editors War Tax Protest. The 528 writers and editors (including Gloria Steinem and Kirkpatrick Sale) pledged themselves to refuse the 10 percent war surtax (which had just been added to income taxes) and possibly the 23 percent of their income tax allocated for the war. Most daily newspapers refused to sell space for the ad. Only the New York Post (at that time, a liberal newspaper), Ramparts (a popular left-wing anti-war magazine), and the New York Review of Books carried it.

Ken Knudson, in a 1965 letter to Peacemaker, suggested that inflating the deductibles on the U.S. W-4 income tax form would reduce the amount of taxes owed. Again, Karl Meyer was instrumental in promoting this idea, which was adopted by Peacemakers, the Catholic Worker, and the War Resisters League, among other organizations in the late 1960s. Inflating W-4 forms also brought a new batch of indictments and jail sentences; 16 were indicted for claiming too many dependents, and of those, six were actually jailed.

The number of known income tax resisters grew from 275 in 1966 to an estimated 20,000 in the early 1970s. The number of telephone tax resisters was estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands. Many groups were formed around the country including “people’s life funds,” to which people sent their war tax resisted money to fund community programs.

The popularity of war tax resistance grew to such an extent that the WRL could no longer handle the volume of requests. So in 1969 a press conference was held in New York City to announce the founding of the national War Tax Resistance (WTR). Long-time peace activist Bradford Lyttle was the first coordinator. Local WTR chapters blossomed around the country, and by 1972 there were 192 such groups. WTR published a comprehensive handbook on tax resistance, Ain’t Gonna Pay for War No More (edited by Robert Calvert), and put out a monthly newsletter, “Tax Talk.” Radical members of the historic peace churches began to urge their constituencies to refuse war taxes.

In 1972 the African-American Democrat Congressman Ronald Dellums of California introduced the World Peace Tax Fund Act in Congress, which was designed to create a conscientious objector status for taxpayers. The National Council for a World Peace Tax Fund was formed to promote this legislation (later changed to National Campaign for a Peace Tax Fund). The bill did not pass but it has been introduced into each Congress since.

During the Vietnam War, war tax resistance gained its greatest strength ever in the history of the United States, and on a secular basis rather than as a result of the historic peace churches, who played a very minor role this time. The government did its best to stop this increase in tax resistance, but was hamstrung by telephone tax resisters. There were so many resisters and so little tax owed per person that the IRS lost money every time they made a collection. The cost of bank levies, garnished wages, automobile and property seizures, and even the simplest IRS paperwork was too expensive to be worth it.

President Reagan’s Military Escalation

National war tax resistance dwindled in 1975 with the end of the Vietnam War. By 1977 war tax resistance dropped to about 20,000 telephone tax resisters and a few thousand income tax resisters. Then in 1978 some radical members of the three historic peace churches got together to issue a “New Call to Peacemaking” that suggested war tax resistance as one way to oppose the arms race. The Center on Law and Pacifism was formed in 1978 to assist these and other war tax resistance efforts, and issued the book People Pay for Peace, by William Durland (1979).

With the election of Ronald Reagan as President in 1980 and his call to rearm the U.S., many more people began to resist war taxes. The IRS admitted that the number of war tax resisters tripled from 1978 to 1981. Like Joan Baez’s tax refusal announcement in 1963, a national stir was created in 1981 when Roman Catholic Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen of Seattle urged citizens to refuse to pay 50 percent of their income taxes to protest spending on nuclear weapons. Letters of endorsement of his stand were made by other religious leaders in Seattle and elsewhere around the country.

In 1982 the War Resisters League published the first edition of The Guide to War Tax Resistance, which sought to provide a broad and comprehensive source of information incorporating the out-of-print Ain’t Gonna Pay for War No More, and Peacemakers’ Handbook on the Nonpayment of War Taxes, as well as new material not included in either book. A fifth edition of the book came out in 2003. About the same time, the WRL began producing its annual “tax piechart” street flyer, which analyzed the military spending of the Federal government to stimulate protests to the military proportion of the budget.

This renewed interest in war tax resistance, spurred on by the unprecedented increase in military spending during peacetime, also brought an escalated response by the government. Though there have been only three criminal prosecutions of war tax resisters since 1980, the IRS shifted tactics and began seizing property. In 1984 and 1985 after almost ten years of very few seizures, about a half dozen automobiles and a similar number of houses were seized from war tax resisters. Furthermore, in 1982 the government came up with a new civil penalty which was specifically aimed at war tax resisters. Called the “frivolous” fine, it charged a $500 penalty against anyone who altered their 1040 forms (e.g., by claiming a war tax deduction).

In an effort to coordinate the growing interest in war tax resistance, a National Action Conference was called by the WRL and the Center on Law and Pacifism in 1982. Out of this conference the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee (NWTRCC) was formed. Every spring NWTRCC has issued press releases announcing Tax Day actions around the country. In addition to a bimonthly newsletter with the latest war tax resistance news, NWTRCC has issued several brochures, produced a slide show, and published the War Tax Manual for Counselors and Lawyers. [Please see NWTRCC’s statement of purpose, which we posted here.]

The End of the Cold War (1989)

In 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall, followed by the collapse of the former Soviet bloc, and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Cold War was said to have ended. War tax resisters and others expected a major reduction in the U.S. military and looked for ways to work in coalition with groups calling for a “peace dividend.” However, a little more than a year later, George Bush sent U.S. troops to the Persian Gulf, and war tax resistance groups were flooded with calls from people saying that they’d “had enough!”

Also in 1989, the IRS seized and auctioned the Colrain, Massachusetts, home of war tax resisters Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner; shortly thereafter, the home of resisters Bob Bady and Pat Morse, neighbors of Kehler-Corner, was also seized and auctioned. Within hours, a support committee was formed. Significant articles appeared in newspapers across the country. After their eviction in 1991, the house was occupied by a rotating collection of affinity groups until 1992, when the new owners forced their way in. A continuous vigil outside lasted until the fall of 1993. Throughout this entire period, considerable publicity, actions, and support were generated bringing a lot of attention to war tax resistance, U.S. military spending, and the misplaced priorities of the government. An Act of Conscience, a 90-minute documentary film about the struggle, was also released.

Also, from 1990 to 1993 the Alternative Revenue Service (ARS) was developed by the WRL and co-sponsored by NWTRCC and the Conscience and Military Tax Campaign. It grew out of a desire, shared by many war tax resisters, to have a nationally organized campaign that would reach out to new communities in a creative way, suggesting that even a token level of tax resistance is a valuable protest. During the 1990-1991 tax season 70,000 EZ Peace forms – a parody of the IRS’s 1040EZ, easy income tax form – were circulated. About 500 forms were returned and over $105,000 in resisted taxes was redirected to alternative funds and other groups. By 1993, a decline in interest made that the last season for the ARS.

Numerous well-publicized cases of IRS abuse led to Congressional hearings in 1997 and 1998, and resulted in the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act. Among the changes, were some reductions in interest and penalties, some restrictions on levies and seizures, reorganizing the IRS away from a geographical structure to one that concentrates on types of taxpayers (individuals, small businesses and the self-employed, corporations, and tax-exempt groups), and a number of more cosmetic (as far as war tax resisters are concerned) changes. The IRS also cut back on the number of collection agents, liens, levies, and seizures of property.

In 1993 Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in an attempt to accommodate individual conscience in instances where a person’s religious beliefs may be adversely affected by the government. In the late 1990s three court cases were filed by Quaker war tax resisters using RFRA and the First Amendment guarantee to the free exercise of religion in an attempt to have penalties against war tax resisters removed and permit them to pay only for non-military programs. These cases were dismissed in lower courts, appealed, then dismissed again in the Second and Third Circuit Courts. In 2000 the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear any of the appeals.

The War on Terrorism (2001-2016)

Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, President George W. Bush began bombing Afghanistan and sent in ground troops to topple the ruling Taliban regime in the name of fighting terrorism. In March 2003, the U.S. launched an all-out war against Iraq, a country with no role in the September 11 attacks. More than 15 years after the U.S. attack on Afghanistan, random bombings, drone strikes, and factional killings have spread to Pakistan, Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Somalia. Since 2001, the wars have cost more than $4 trillion, killed 1-2 million civilians, and created millions of refugees fleeing the violence.

War tax resisters acted in coalition with millions of others around the world to stop the invasion of Iraq and have continued to campaign against war spending ever since. In 2003 one of the largest public acts of war tax resistance and redirection occurred when environmental activist Julia Butterfly Hill announced, as her protest to the War on Terrorism, her refusal to pay $100,000 in federal income taxes that she owed as a result of a legal settlement. The Iraq Pledge of Resistance initiated an internet-based telephone tax resistance campaign, Hang Up On War, that was endorsed by a coalition of groups. Resisters developed an alternative tax form, a “Peace Tax Return,” to simplify resistance.

In July 2007 the Associated Press (AP) ran an article, “Fed Up With War, Some Won’t Pay Taxes” by John Christoffersen that brought significant attention to war tax resistance. The group Code Pink launched an online tax resistance pledge called “Don’t Buy Bush’s War,” and National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee started the War Tax Boycott campaign and collected pledges of about $400,000 of redirected tax money to donate to organizations helping victims of war.

Six war tax resisters were jailed between 2006 and 2010 (but none to date since then), and the IRS continues to pressure individuals to pay, or seizes money from bank accounts and salaries. With the ongoing wars and the increased militarism in the U.S., the peace movement and war tax resistance should have grown, but during the Obama presidency peace activism slipped into the background. In 2010 the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee produced a half-hour video, Death and Taxes, about war tax resistance, which featured interviews with 28 people explaining why they resist.

The Occupy movement brought attention to income inequality, and war tax resisters were active in that movement. More recently, climate change and Black Lives Matter have moved to the forefront of activism in the U.S., but longtime peace movement groups carry on their work and war tax resistance has maintained a steady if not growing network.

In late 2016, facing the incoming administration of Donald Trump, activism for justice and peace is on the increase again, and war tax resistance is getting a new look.

EDITOR’S NOTE: For more information on the history of war tax resistance, see the War Resisters League’s publication, War Tax Resistance: A Guide to Withholding Your Support from the Military, available via their website. Our thanks to WRL for permission; www.warresisters.org.