Guest Editorial: The Sexuality of a Celibate Life

by Vinay Lal

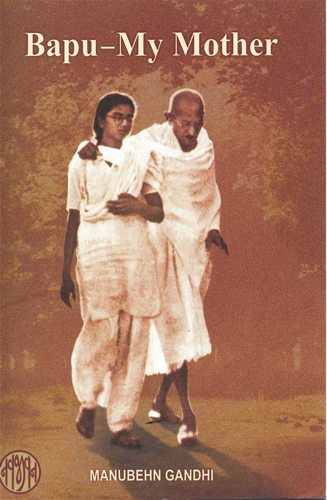

Book cover art courtesy navajivantrust.org

A celibate for the greater part of his life, Mohandas Gandhi continues to attract nearly unrivalled attention – often for the sex that did not take place. Even his friends and admirers, who revered him for bringing ethics to the political life, or for never demanding of others what he did not first demand of himself, were quite certain that Gandhi was unable to comprehend that a woman and a man might enjoy a perfectly healthy sexual relationship with each other. Nehru, seldom critical of the personal life of his political mentor, was convinced that Gandhi harboured an “unnatural” suspicion of the sexual life; and he deplored, as did many others, Gandhi’s strongly held view that sexual intercourse, other than for purposes of procreation, had no place in civilised life – not even among married couples. The Marxists have long subscribed to the view that Gandhi was a “romantic”, a hopeless idealist and even hypocrite; to this a chorus of voices added the thought that Gandhi was an insufferable “puritan”.

Gandhi’s discomfort with the sexual life, according to one widely accepted strand of thought, commenced when his father passed away shortly after his marriage to Kasturba. Though the young Gandhi liked to nurse his ailing father, one evening he was unable to contain his urge to share a night of ribaldry with his young wife. He had just withdrawn to the bedroom when a knock on the door announced that his father had passed away. Gandhi was, it has been argued, never able to forgive himself his transgression, and became determined to master his sexual drive. A more complex narrative links his renunciation of sex to his firm conviction, first developed during the heat of a campaign of nonviolent resistance to oppression in South Africa, that it compromised his ability to be a perfect satyagrahi. Many commentators have pointed to his failure to consult with Kasturba before he took a vow of celibacy at the age of 37 as a sign of his cruelty and tendency to be self-serving.

One British reviewer of Joseph Lelyveld’s new biography of the Mahatma, however, had much more than this in mind when he characterised Gandhi as a “sexual weirdo”. In his 70s, in the sunset of his life, Gandhi embarked on a new set of sexual experiments in which several women partook, among them Manu and Abha, his “two walking sticks”, and Sushila Nayar, his personal physician and sister of his secretary Pyarelal. In the midst of raging communal violence, which Gandhi characteristically attributed to his own personal shortcomings, he decided to test his resolve – by going to bed naked with one or the other of the women. His detractors have ever since had a field day: though no one has ever suggested that Gandhi made improper advances, or that the encounter was in the remotest manner sexual, the mask is supposed to have come off the “dirty old man”. Few of his critics are aware that after such experiments came to a halt, Manu penned a remarkable little book titled, Bapu, My Mother; or that Sushila Nayar, furnishing an account several years after Gandhi’s death of these experiments in brahmacharya, stated that, far from experiencing any sexual desire, she felt as though she was sharing the bed with her mother.

The celibate Gandhi is as much a conundrum as any other Gandhi we have known. Though the principal architect of the Indian Independence struggle, he had much less invested in the idea of the nation-state than any other nationalist. He was a radical democrat but one detects a streak of authoritarianism in his political conduct; and, similarly, while declaring himself a bhakta devotee of Tulsidas, he never doubted that passages in the great poet’s Ramacharitmanas (Tulsidas’s Hindi retelling of the Ramayana), that were repugnant to one’s moral conscience were to be rejected.

The vow of brahmacharya did not preclude, as it has for reformers and saints in Indian religious traditions, the company of women; indeed, Gandhi adored their presence and reveled in their touch. He was constantly surrounded by women, and for decades Mirabehn, the daughter of an English admiral who was mesmerised by the Mahatma, was privy to his innermost thoughts to such an extent as to arouse Kasturba’s jealousy. Their correspondence has a touch of the erotic; and, Mirabehn, in particular, would write of her longing for the Mahatma when he was away. She was by no means the only woman with whom Gandhi enjoyed a platonic relationship: there was an intense exchange of “love letters” over many years between him and Esther Faering, a Danish missionary, and Saraladevi Chowdharani was cast as his “spiritual wife”. Many of his male friendships are equally interesting: for example, he may also have been attracted to Hermann Kallenbach, a wealthy Jewish architect who would become one of Gandhi’s earliest patrons and closest friends. Kallenbach, a body-builder and athlete, may have been the embodiment of masculinity, but Gandhi saw his soft side and his gift for nonviolence.

We are not likely to understand these friendships, which should also make us aware of Gandhi’s singular disinterest in the traditional concept of the family, if we fail to make a distinction between sex and sexuality and see through to the core of his thoughts on masculinity and femininity. Though Gandhi repudiated sex, which he saw as a finite game, finite in that its end seemed to be mere physical consummation, he was a consummate player of sexuality who delighted in the infinite pleasures of touch, companionship, and the eroticism of longing and withdrawal. More so than any other Indian political figure of his time, Gandhi made very little distinction between men and women. This will appear to be a brazen statement to those who have read his unequivocally clear pronouncements on the distinct duties of women and men and the spheres they ought ideally to occupy in life. In practice, however, he fundamentally treated them as alike, endeavouring also to bring out something of the feminine in men and something of the masculine in women. It is wholly characteristic of the Mahatma, a relentless advocate of experiments with truth, that even if he appeared to work with a crude conception of what it means to be male or female, his entire life can be read as an attempt to bring us to a new threshold of understanding the notions of masculinity and femininity.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Vinay Lal is Professor of History and Asian American Studies at UCLA. He writes widely on the history and culture of colonial and modern India, popular and public culture in India (especially cinema), historiography, the politics of world history, the Indian diaspora, global politics, contemporary American politics, and the life and thought of Mohandas Gandhi. He is the author or editor of over fifteen books. His exceptional blog site gives a full biography, and list of his publications. It is regularly updated with a wealth of articles on India and Gandhi; article courtesy of the author, and The Asian Age, 1 May 2011.