Gandhian Economics for Peace

by Robert Ellsberg

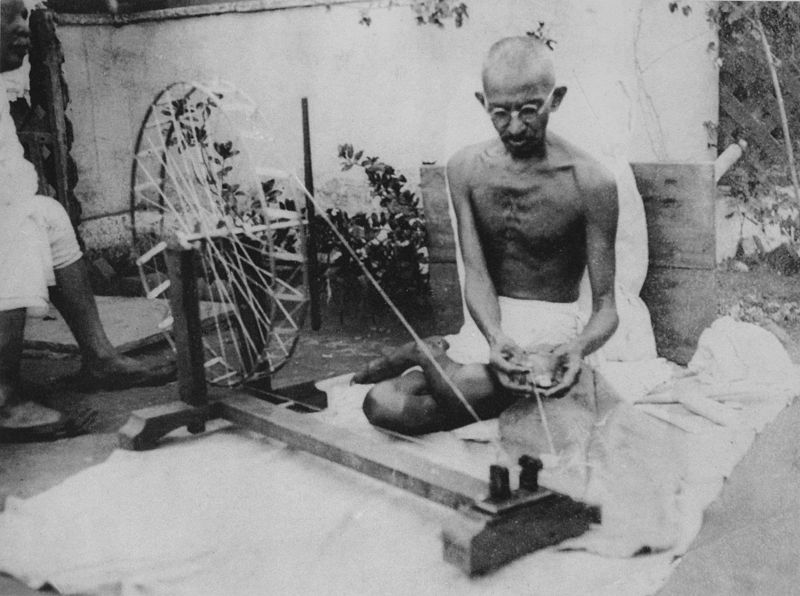

Gandhi spinning, c. 1945; photographer unknown; courtesy of wikipedia.org

“The outward freedom that we shall attain will only be in exact proportion to the inward freedom to which we have grown at a given moment. And if this is the correct view of freedom our chief energy must be concentrated upon achieving reform from within.” M. K. Gandhi

Thomas Merton observed that Gandhi’s spirit of nonviolence “sprang from an inner realization of spiritual unity in himself. The whole Gandhian concept of nonviolent action and satyagraha is incomprehensible if it is thought to be a means of achieving unity rather than as the fruit of inner unity already achieved.” Satyagraha in its sense of truth-force, or soul-force as Martin Luther King called it, could not be a means for overcoming division, unless it represented in itself the active experience of the unity of life; it could not secure a peace from without that was anything but the gift of its own being, a love rooted beneath the surface of things. For the satyagrahi each battle must first be fought in the soul—the battle against selfishness, attachment, passion. One could hardly begin the outer struggle—to wean the opponent from his or her selfishness, attachment, and passion, until the inner battle had been fought, and Truth had been victorious. The task was merely to re-enact that struggle on a larger stage. Truth never engaged in a struggle that had not already been won.

It would be untrue to maintain that nonviolence adopted as a tactic or policy could not achieve results. In that sense the Congress Party of India adopted nonviolence, and in that sense it achieved its objective, viz. independence from England. But Gandhi’s swaraj (self-rule) was not merely a political objective, but a moral calling; not freedom from English rule but freedom from ignorance, exploitation, and violence—the replacement of the rule of force with the rule of love. It was the enemy within— hatred, greed, and fear—that had to be overcome. The withdrawal of Britain would be among only the outward expressions of that achievement.

In the practice of satyagraha one must make of one’s own body (as many Vietnamese Buddhists did in a literal way) a demilitarized zone. No matter how small initially, that source of light might eventually engulf both adversaries. In the same way, swaraj must be exercised by an individual who refuses to be ruled by, and disdains to rule, others. Then freedom must spread to the village, the district, and the province, until freedom from within would steal the country back from its exploiters. The service of India’s liberation was a sacred mission, for in it lay an opportunity for the liberation of humanity.

The Essence of Slavery

Gandhi believed that exploitation was made possible by the active and passive cooperation of the exploited themselves. How else to explain that a single trading company, eventually reinforced by a few thousand soldiers, held hundreds of millions in captivity in their own land? India’s moral weakness and divisions of religion, caste, class, and language, were Britain’s strength. Also, the nation’s educated were enthralled by Western culture and manners. A country that had been self-sufficient for food and clothing for thousands of years and had been one of the principal exporters of textiles for centuries had become impoverished in the space of a hundred years. Land was taken up for the cultivation of cash crops like indigo; food was hoarded by profiteers, and famine for the first time swept over the countryside while wheat was exported to England. Peasants were forced to sell all their crops to pay the massive taxes, only to repurchase their own food at increased prices. Government-supported moneylenders gave credit to farmers at staggering interest rates. The cottage textile industry was ruined with the importation of cheap English cloth made from Indian cotton.

The village industries, which had supplied the peasants with 20-60% of their income as well as meeting their basic needs, were destroyed. With nothing to replace these industries, the villages, once the cradle of Indian civilization, fell into ruin and stagnation. The cities, strongholds of British power and money, began to swell, draining the countryside of its population and wealth, as the country grew deeper into dependence on Britain.

How to respond to this? Resistance, certainly, but of what kind? The essence of slavery was in the slave’s willing acceptance of that self-image. We must non-cooperate with the oppressor at least to the extent of refusing to allow his perception of us to determine our own self-image. To gain in self-respect and dignity was an assertion of a consciousness of independence. At the same time, we must assert our respect for the individuality of the oppressor, refusing to indulge him in his own self-image. To non-cooperate meant not merely to boycott foreign goods and institutions, but to refuse to adopt the foreign ways and values of the oppressor and to develop a respect for our own. It meant this to the extent that we must refuse to let our means be determined by the means of the oppressor, in other words we ourselves must refuse to exploit others. Gandhi pleaded that liberation of the “untouchables” was the key to swaraj, or self-rule. India could not subjugate these millions while pleading for deliverance from the inhumanity of others. No less was swaraj to be found in the protection of tribal peoples, the uplifting of women, even service of lepers. “I am deliberately introducing the leper as a link in the chain of constructive effort. For what the leper is in India, that we are, if we will but look around us, for the civilized world.”

Non-cooperation meant, in essence, the refusal to acknowledge, through participation, a slave-master relationship or tutor-pupil as the British preferred to consider it. Gandhi foresaw that the end of British rule would date from the moment they were compelled to negotiate with him as a free man. This subversion of the opponent’s definitions and categories was the most vital kind of resistance. It was not necessary to push for immediate total concession from the British.

Nonviolent Economics

But mere “consciousness of independence” would bring little solace to the poor and oppressed, and mere speech-making would not change the actual economic dependence into which India had sunk. The nonviolent economic revolution was aimed ultimately not only at ending British oppression, but also at bringing an end to all economic oppression. This meant not promoting new masters in place of the old; the people must become their own masters. This process would be simultaneous with the decentralization of the economic and political base of the country—distribution among the common people of the means of satisfying basic needs and of determining political issues. Until then, who ruled from Delhi would make no actual difference to the people’s dependence. A starving man would trade his liberty for a piece of bread, Gandhi observed. A way had to be found of responding to the immediate needs of the poor while simultaneously building the future.

Gandhi believed that the source of strength and continuity in Indian tradition had been the village. The greatest accomplishment of British imperialism had been the ruin of the village economy, the prerequisite for the establishment of a mercantile relationship. The economic basis of the freedom struggle as well as the foundation for a future nonviolent society must be the revival of village autonomy and self-sufficiency. If swaraj meant, in part, refusing to be an exploiter, it meant nothing if not economic equality, the leveling down of the few rich and the leveling up of the masses of helpless poor, and independence for the villages from the crushing weight of the cities. That split between town and country was the chief source of inequality in society. Centralization of production had meant the destitution of the masses and the decay of India. To reverse this process would be to withdraw the footholds of imperialism and bring immediate relief to the poor millions.

To an astonished nation Gandhi claimed that England would be forced to relent by the power of the weapon of peace, the charka, or spinning wheel. If all Indians spun to clothe the nation, England would have no choice but to leave without a fight. Nehru called khadi (hand spun cloth) the “livery of freedom.” While manufacture of khadi was of course a practical aspect of the boycott of foreign cloth, it was also something more. Gandhi encouraged the boycott of cloth manufactured in Indian mills as well. Such capital-intensive means of production in a land of idle millions was prompted, not by economic considerations, but by greed, and was thus an instrument of exploitation. Khadi was the beginning of a silent economic revolution whose effects would extend far beyond any short range political goals.

To understand its meaning we must look to Gandhi’s economic philosophy, noting first two things: that his economics, like all his thought, arose neither from armchair idealism, nor was it derived from a “scientific” study of history, but from his observation and experience of particular needs. Therefore his theories were deliberately unsystematic and intended not to represent immutable laws but simply scattered discoveries from his lifelong experiments. Secondly, we should keep in mind perhaps the most important lesson, that all his economic thought reflects his belief that the aim of social organization and planning should be the progressive realization of the virtues of Truth and nonviolence within society.

As Gandhi wrote, “True economics never militates against the highest ethical standards, just as all true ethics, to be worth the name, must at the same time be also good economics. An economics that inculcates Mammon worship and enables the strong to amass wealth at the expense of the weak is a false and dismal science. It spells death. True economics, on the other hand, stands for social justice; it promotes the good of all equally, including the weakest, and is indispensable for a decent life.”

According to Gandhi, economics is concerned with the moral as well as the material progress of a country. All expansion of material prosperity must be directed with a view to attaining that moral development by which is meant social justice, as well as ultimate values such as freedom, peace, and human happiness. This is to say that beyond assuring essentials for material well being, clothing, food, and shelter, affluence is not to be pursued as an end. “Civilization in the real sense of the term consists not in the multiplication, but in the deliberate and voluntary reduction of wants. This alone promotes real happiness and contentment, and increases the capacity for service.”

Gandhi penetrated the core of the economics of Western civilization, its essential irrationality: consumption elevated as the sole incentive and source of fulfillment precisely because it was not available to everyone; a sophisticated technology that generated and was sustained by unfulfilled fancies; poverty in the midst of plenty, and profit for the few derived from the unemployment of the many; an abundance altogether sustained by theft.

Happiness could be provided any society without all the mind-boggling benefits of advanced technology as long as its wants were few. Gandhi distinguished between a high standard of living and high standard of life, the former more appropriately called the complex way of living, promoting neither health nor beauty, freedom nor joy. Western economics was based on conflict, and conquest of the earth and human nature. How could such a system survive? It raised efficiency, technology, speed and growth, which have no virtues of their own except in so far as they serve human needs, into ends in themselves. With no sense of balance, no sense of real ends, this idolatrous obsession with results, efficiency, consequences, had the effect of making all of real value inconsequential. Western economies plundered the earth of irreplaceable resources, and violence against the earth all too easily became violence against people. A nonviolent economy would emphasize not conflict but cooperation, not conquest but harmony with nature. Gandhi called the nonviolent economy the economy of permanence. It was held together not simply by necessity and self-interest, but by mutual trust and fellowship.

“According to me the economic constitution of India and for that matter of the whole world, should be such that no one under it should suffer from want of food and clothing. In other words, everybody should be able to get sufficient work to enable him to make the two ends meet. And this ideal can be universally realized only if the means of production of the elementary necessaries of life remain in the control of the masses. These should be freely available to all as God’s air and water are and ought to be. They should not be made a vehicle of traffic for the exploitation of others.”

Decentralism

Gandhi called economic equality “the master key to nonviolent independence.” He opposed ownership of the means of production and the consequent private accumulation of capital. Wealth is not the fruit of individual but cooperative effort and therefore no individual should have a right to its claim except in order to hold it in trust for the welfare of society. Yet centralized production under collective (state) ownership was not necessarily preferable since Gandhi believed the basic problem to be the separation between production and distribution. Distribution, he felt, could be equalized only where production is localized, in other words, where distribution and production are synonymous. The issue was not between capitalist private property and collectivized property but between centralization and decentralization.

Decentralization was most consistent with nonviolence. It did not require the unnatural concentration of population and all the coercion involved in urban life; it required no armed forces in its defense; it provided security to the masses without overwhelming the individual—on the contrary, enhancing the capacity among individuals for creative and cooperative effort, fostering independence, dignity and self respect. It thus served the end of human happiness combined with full mental and moral growth.

Decentralism was economic democracy; not organization imposed from above but arising from below, a willing understanding between cooperating units. The nonviolent organization that Gandhi described, unlike a pyramid in which the apex is supported by a massive base, would be a series of “oceanic circles,” mutually reinforcing one another, each willing to sacrifice all for the welfare of each. Technology and science would be used to ensure democracy while maximizing production and employment. Mass production, said Gandhi, is production by the masses. His greatest example of this was khadi.

Sharing the Labor of the Poor

Gandhi believed that every man, woman, and child in country and city should spin for a minimum of one hour daily. For the impoverished rural masses forced into idleness six months out of the year, spinning would provide a steady source of income, while at the same time helping them directly to satisfy basic needs. For the urban population, spinning would be a productive contribution to the cost of their daily support, as well as a bridge with the countryside. For the intellectuals and nationalists, khadi offered a way of sharing the toil of the poor, the beginning of social equality on the basis of respect for the equality of all labor.

“I can’t imagine anything nobler or more natural than for say one hour in the day, we should all do the labor that the poor must do, and thus identify ourselves with them, and through them with all mankind. I cannot imagine better worship of God than that in His name I should labor for the poor even as they do.”

Though, strictly speaking, mill cloth was cheaper than khadi, Gandhi insisted that this was an illusion, moreover a typical consequence of the division between economics and ethics. Such a view ignored the larger total costs, the social costs in unemployment, disruption of village life, impairment of the balance between manufacture and agriculture, and ecological damage. We might include national costs as well, in that each penny spent on mill cloth went to England to finance India’s subjugation. The charka, adaptable to the moral and aesthetic possibilities of human nature, was far less expensive for society. But there were those who wondered whether Gandhi was not simply against machinery.

“How can I be when I know that even this body is a most delicate piece of machinery? The spinning wheel itself is a machine. What I object to is the craze for machinery, not machinery as such. The craze is for what they call labor saving machinery. Men go on “saving labor” till thousands are without work and thrown on the streets to die of starvation. I want to save time and labor not for a fraction of mankind but for all. I want the concentration of wealth, not in the hands of a few, but in the hands of all. Today, machines merely help a few to ride the backs of millions. The impetus behind it all is not the philanthropy to save labor, but greed. It is against this constitution of things that I am fighting with all my might.”

His basic demand of technology was that its use be determined by the physical and spiritual good of society.

Bread Labor

Central to the principle of khadi and in the background of all Gandhi’s economic theory was the philosophy of bread labor. This was the moral law from which no healthy individual was excused, that one must perform physical labor for one’s daily bread—in other words, that one must contribute through manual labor to the satisfaction of one’s basic needs. Not to offer labor would mean to steal our food from the one who had produced it. By bread labor one fulfilled an obligation to society, returning to one’s neighbors something of the measure that one took. All labor producing such essentials as food and clothing was authentic social service. By serving one’s neighbors in this way, one served humanity. Bread labor was thus more than an idealization of physical work; it was a principle of personal responsibility. It contained the idea that intellectual skills were to be used in the service of society and not for personal gain. Ideally, doctors, lawyers and teachers would donate their services to the community. Gandhi identified bread labor with the religious concept of yajna, an act directed to the welfare of others, performed without desire for return. Yajna, or sacrifice, was the path to freedom and fulfillment.

“Brahma created his people with the duty of sacrifice laid upon them and said, ‘By this do you flourish. Let it be the fulfiller of all your desires.’ He who eats without performing this sacrifice eats stolen bread.” An hour of spinning a day was thus a religious duty. If observed by everybody “all men would be equal, none would starve, and the world would be saved from many a sin.”

The principal source of exploitation in society is the claim by some of exemption from the law of bread labor. Whatever the excuse, the effect is the same, to shift the burden for one’s existence onto the backs of others. Of this deceit Gandhi accused not only the capitalist class but those intellectuals who believed their degrees absolved them from the responsibility of productive labor. Those who felt that intellectual labor fulfilled their obligation should eat intellectual food. “The needs of the body must be fulfilled by the body.”

“Obedience to the law of bread labor will bring about a silent revolution in the structure of society. Man’s triumph will consist in substituting the struggle for existence by the struggle for mutual service. The law of the brute will be replaced by the law of man.” Bread labor was contained in Gandhi’s vow of non-stealing. We must work to satisfy our needs and reduce our wants to those things, which we can produce for ourselves. In this way our wants would be minimized and our lives simplified. “We should then eat to live, not live to eat.”

Furthermore we should class as stolen property those things we possess without needing. It was in this spirit that St. Basil said, “Art thou not a robber, thou who considers thine own that which has been given thee solely to distribute to others? This bread which thou hast set aside is the bread of the hungry; this garment thou hast locked away is the clothing of the naked; those shoes which thou hast not worn are shoes for him who is barefoot; those riches thou hast hoarded are the riches of the poor.” As devotees of love and truth we must rest in faith that our daily bread will be provided as well as everything we require. In the freedom that comes of giving joyfully, in devotion to the Truth, service of our brethren and not bread, may become for us the staff of life.

Bharatan Kumarappa, a Gandhian writer, has said, “A man whose needs are few such as can be met by himself can afford to raise his head high and refuse to bow to any power which seeks to enslave him. Not the man with a so called high standard of living. Every new luxury he adopts becomes an additional fetter preventing him from freedom of thought, movement and action.”

Self-rule: Struggle for Truth

Gandhi realized that true swaraj could not be won by leaders who envied and identified with the civilization of their colonial masters. It was not true that Gandhi denied that nonviolence as a policy would effectively expel the British. It was the perception of this goal as a limited one that made tactical nonviolence, in his eyes, a misguided and limited means. The slavish imitation of Western economic policies by the Congress government from the first years of independence (and the oppressive consequences that become more obvious each day) more than justify Gandhi’s fears. After thirty years of “socialist” rule, over a period that has seen national income increase eleven times, the gulf between rich and poor by all calculations has increased.

Gandhi did not believe in devising a blueprint for the future. “One step is enough for me,” he was fond of repeating. For him the struggle for self-rule was the constant individual struggle for truth that would continue beyond Independence, and indeed beyond any of our lifetimes. We cannot know the distant goal. It is determined not by our words nor by our decisions and definitions, but by our actions now. We shape the future and we shape ourselves. Gandhi did not distinguish between his personal experiments and his public mission. Outer freedom is never more than the expression of inner freedom already attained. This was his constant message. Are we now struggling against our present chains by forging future ones? To the person imbued with the spirit of giving, no thief can pose a threat. For one filled with an interior silence no noise can be a distraction. Yet if one does not have that inner peace, even outer silence is deafening.

The difference between voluntary and involuntary poverty is principally a difference of attitude. Yet one condition is slavery while the other is joy and freedom. Little would be gained by an independence that preserved the corruption and division that was the source and product of British rule. The most important task was shaping the attitude of the people, awakening them to a sense of power not conferred from without but realized from within—the power that comes from unity and inner freedom. Not the guns of the British, nor the police of Indira Gandhi, but the failure to realize this power has kept India, as it keeps all of us, in submission. The work of the true revolutionary is to re-awaken from day to day that consciousness of freedom in oneself and others, preparing in interior silence and consecrated action a place for the future to be born.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Robert Ellsberg (b. 1955) is editor in chief of Orbis Books, the publishing wing of the Maryknoll Society. He graduated from Harvard College with a degree in religion and literature and later earned a Masters in Theology from Harvard Divinity School. From 1975 to 1980 he lived at the Catholic Worker community in New York City, and was the papers managing editor from 1976-78. He is the author of a number of bestselling books, including All Saints: Daily Reflections on Saints, Prophets, and Witnesses for Our Time, which won a Christopher Award and a Catholic Book Award. His Blessed Among All Women won three Catholic Book Awards. Robert is also the son of the famous “whistle-blower” Daniel Ellsberg. Article courtesy of Marquette University and the CW; per issue of January 1976; pp. 1, 4, 5, 7.