Dorothy Day Biography Raises Universal Questions

by Dana Greene

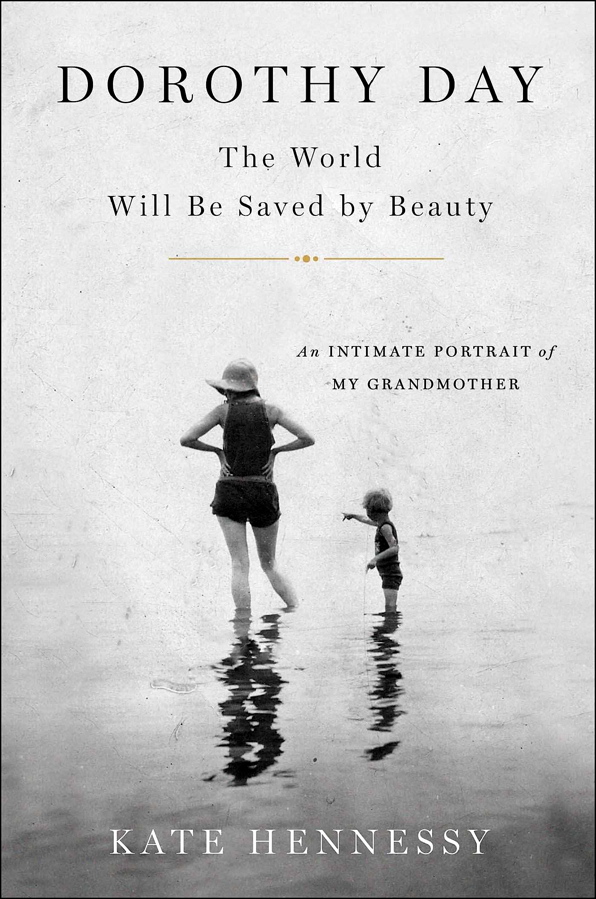

Dustwrapper art courtesy Scribner; simonandschusterpublishing.com/scribner

Who was Dorothy Day? In his address to Congress, Pope Francis named her an American icon of the stature of Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr., and New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan is among those moving her case forward for canonization. There are abundant materials documenting Day’s life and contributions — her autobiographies, letters, diaries, hundreds of her Catholic Worker columns, and a spate of biographies by Robert Coles, Jim Forest, William Miller and others.

One might ask whether another biographical venture, this one written by Day’s youngest granddaughter, might be redundant or sentimental? It is neither. Kate Hennessy’s biography, Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty; An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother (New York: Scribner, 2017) offers valuable insights into understanding this “complex,” “restless,” “bullheaded,” “judgmental” and “contradictory” woman who in her life railed against being referred to as a saint. It is a clear-eyed, tough but tender telling of Day’s life that goes far in saving her from the hagiographic “embalming” that so often accompanies saint-making.

Hennessy’s “insider” story is unique, a family biography linking Day with her daughter, Tamar, and Day’s nine grandchildren, most prominently Hennessy herself. It opens with the story of Day’s early life, her sense of not belonging, and then the Bohemian years of this “Northern Communist whore” in the 1920s and 30s.

Her socialist commitments, her salty language, heavy smoking, hard drinking, abortion, and a love affair with Forster Batterham, father of Tamar, are all chronicled here, as are Day’s commitments to journalism and social activism. Her decision to have Tamar baptized a Catholic in order to give her daughter’s life meaning and prevent her from floundering as she had done, is particularly moving. So is her decision to leave Batterham, whom she loved, because he would not marry her, believing as he did that marriage was tyranny and Catholicism folly.

Day always claimed that the arrival of Peter Maurin in her life was a grace. According to her, it was he who was the founder of the Catholic Worker, but, true or not, it was Day who kept it going. In the depression, the Catholic Worker fed a thousand people a day, and almost 200,000 copies of its newspaper were distributed in one week in the 1930s. The paper remains in print, still costing a penny a copy, and some 250 Catholic Worker houses of hospitality continue to serve the most destitute.

Day’s early life, her conversion and the creation of the Catholic Worker movement are well documented. What is less well known, and what Hennessy brings to light, are Day’s familial relationships — as a single mother, her raising of Tamar, and the tensions that developed between them.

Day’s parenting of Tamar is juxtaposed with life at the Catholic Worker in both New York City and its several farms. Hennessy captures the smells, the dirt, the poverty and hardship of these places, and the profound needs of those who visited them. At the center of the welter, confusion and endless privation was the matriarch, Dorothy Day, who struggled to pay bills, ensure food, settle fights among the disgruntled and the mentally ill, and push back those who wanted to diminish her authority. The circumstances of life for Dorothy and Tamar were difficult and chaotic, but Hennessy’s telling gives the reader confidence that she is portraying life as it was actually lived.

Because Dorothy was a public person — a writer, an activist, a frequent speaker — she was often absent and hence was criticized for not fulfilling society’s expectations of a mother. Tamar suffered and felt undervalued. Although she always loved the sense of community of the Catholic Worker and its commitments to voluntary poverty and living from the land, Tamar, mother of nine, had her own personal struggles that her daughter Kate attempts to understand.

The importance of this biography is not only that it details the familiar life of Dorothy Day, but it raises universal questions that are not easily answered. What is the appropriate relationship between a woman with a prophetic vocation and her maternal responsibilities? How does one both live within the church and criticize it?

In Day’s case, she chastised the hierarchy for lavish living and its refusal to condemn nuclear weapons, but she was silent about its patriarchy. How does one sustain decades of social commitment to the most marginalized and simultaneously oppose societal injustice? Day not only fed, housed and cared for society’s refuse, she was a pacifist, opposed the development of nuclear weapons, fought for civil rights, and defended farm workers and the right to unionize. She was arrested for the last time when she was 76.

Day maintained that faithfulness and perseverance were the central virtues, and she witnessed to them with her life for 50 years, even though at the end she believed she was a failure. What calmed her restlessness was reading the Psalms, prayer, and especially the Eucharist. Although bored by theology, she was nurtured by writing; she considered it a form of prayer. When the world seemed disordered, she escaped to nature, to the sea or to reading, each renewing her experience of beauty. She believed, with Dostoevsky, that it was beauty that would save the world.

A quip that circulated at the Catholic Worker was that martyrs were those who lived with saints. As Day’s case moves through the lumbering process for sainthood, one can ask what weight should be given to the testimony of those who knew her?

What Hennessy provides is abundant evidence of the humanness of this lay American Catholic woman. What Day teaches uniquely is a method of living that was embodied in the one-liner she offered me when I once met her at a workshop opposing nuclear weapons. My earnest query was, “What must be done next?” She replied: “First scrub the toilets.” It was a reminder that one must return again and again to the bottom where human need is greatest.

Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty is an accessible, provocative read that, like all good biography, leaves one confronting the ultimate mystery of the human person: Dorothy Day, full of contradiction yet exemplary in her faithfulness.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dana Greene is the author of biographies of Evelyn Underhill, Maisie Ward, and Denise Levertov. Her biography of the English poet Elizabeth Jennings is forthcoming from Oxford University Press. Reprinted with permission of National Catholic Reporter Publishing Company, Kansas City, MO; NCRonline.org.