Statement of Purpose

In conjunction with War Resisters’ International in London, we have embarked on researching the enormous WRI archive held in Amsterdam by the International Institute of Social History (IISG). The archive occupies 63.3 meters of IISG shelf space, with spill over material in approximately 12 other IISG archives. The purpose of our project will not be, of course, to post anything or everything, but rather to make a selection of material that demonstrates the influence of nonviolence on the early 20th century peace movements, and vice versa, especially the period c. 1910-1950, that is, from the years leading up to WWI, to the aftermath of WWII. For each of the articles that follow we have provided notes and in some cases prefaces to help make the material more accessible. Each article also contains a “Reference” to the location of the material at IISG. Our Pacifism Editor, Gertjan Cobelens, is in charge of the project, and correspondence may be sent to him via our contact page.

by Mohandas K. Gandhi

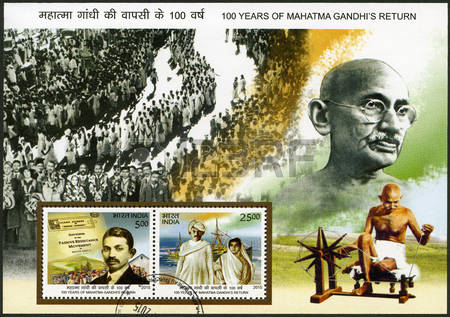

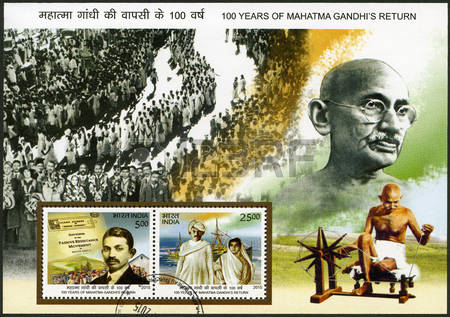

Gandhi poster commemorating his 1915 return to Indian from South Africa, courtesy www.123rf.com

Editor’s Preface: This is the last in our series of articles from the IISG/War Resisters’ International archive; it was first published in the May 3, 1946 issue of Peace News. We have selected this particular article because of Gandhi’s criticism of destruction of property, a tactic used by the Vietnam War protest movement, as with the burning of draft files. The discussion was later revisited by Occupy, and especially Occupy Oakland. Please also consult the notes at the end. JG

“I plead now for non-violence and yet more non-violence.” M. K. Gandhi

Hatred is in the air and impatient lovers of India will gladly take advantage of it, if they can, through violence, to further the cause of independence. That is wrong at any time and everywhere, but it is more wrong in a country where fighters for freedom have declared to the world that their policy is truth and non-violence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Gertjan Cobelens

Bertrand Russell (right foreground) leads Committee march; courtesy peacebuttons.info

We are posting today (see below) three previously unpublished articles from the Committee of 100 archive, held by the IISG in Amsterdam, as part of our ongoing research into the early influence of nonviolence on the pacifist movements. During the summer of 1960, philosopher and activist Bertrand Russell was persuaded to resign his presidency of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and assume the leadership of the Committee of 100, a newly planned movement for large scale nonviolent direct action against the manufacture and use of nuclear weapons. Together with Michael Scott, Ralph Schoenman, Michael Randle, April Carter and 95 other public signatories, 88-year-old Russell launched the Committee at a meeting in London on 22 October 1960. Its objective was to stop the “folly of nuclear armaments” through mass civil disobedience.

Right from the beginning the Committee of 100 strongly emphasized the nonviolent nature of the demonstrations, and anybody who wished to participate had to adhere to a long list of behavioral guidelines designed to safeguard the nonviolent integrity of the movement. Nevertheless, demonstrators expected to be arrested and charged and at the second of the sit-down demonstrations in April 1961 in London, over 800 people were arrested. That September, a week before the next mass demonstration, all one hundred committee members were summoned to court without charge for incitement to commit breaches of the peace. They were asked to sign a promise of good behavior for twelve months, but 32 refused, including Bertrand Russell, who opted to go to jail instead. The September demonstration was the largest organized by the Committee. Between 12,000 and 15,000 demonstrators flooded into the center of London, and more than 1,300 were arrested.

Read the rest of this article »

by Peter Cadogan

Aims: To ban the bomb. To prevent World War III. To rid the world of the power of militarists and military alliances. To understand the causes of war and to work out how to eliminate them. To identify the particular people, interests and factors making for World War III.

In face of the threat of war to alert people in Britain and throughout the world to the necessity of building a new kind of national and international movement against war. To achieve our purposes by direct action, without violence and by civil disobedience when need be. To give incidental support to conventional methods of opposition.

Read the rest of this article »

by the London Committee of 100

The London Committee of 100 is a body formed to organise mass nonviolent resistance, including civil disobedience, to nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction. This is a nonviolent demonstration. If you feel that you are not capable of remaining nonviolent in the circumstances of the demonstration, we would ask you not to take part. If at any time during the demonstration you feel that you are going to become violent, we would suggest that you leave the demonstration, at least for the time being.

Read the rest of this article »

by National Committee of 100

Despite the dangers of nuclear tests and the possibilities of nuclear war, we believe that there is hope. Despite the obstacles, we believe that:

- Men are capable of sanity and courage;

- Men can be moved to action to preserve life;

- Effective action is possible.

Read the rest of this article »

by Fred J. Blum

Logo Shanti Sena World Peace Network; courtesy mettacenter.org

Editor’s Preface: The Peace Brigade was organized in 1981 by Narayan Desai and others in London, as an extension of the Shanti Sena, or nonviolent peace force, which Vinoba Bhave had founded in India in the 1950s. Bhave had, of course, taken his name and concept from Gandhi and more specifically from Gandhi’s Constructive Programme. This previously unpublished article makes clear that activists in the U.S. nonviolence and peace movements were already thinking of forming their own chapters as early as 1961, the date on the manuscript. The Brigade still continues in many countries under various names such as the World Peace Brigade, Peace Brigades International, Muslim Peacemaker Teams, etc.. The article is another in our series from the IISG archive in Amsterdam. For further information and references please consult the notes at the end of the article. JG

What is nonviolence? When I thought about how I wanted to start this discussion I felt a need to give some initial broad definition. The first that came to my mind was “to refuse to use violence and to substitute for it other means.” As soon as I had written it down, I felt that the term “to use violence” was very limiting, and expressed a mode of thinking so prevalent today that none of us could easily escape from it, namely a thinking in instrumental terms: of using techniques, of making “things” an instrument for our purpose, for controlling our environment, etc.

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

Logo Sri Lanka sarvodaya; courtesy lightmillennium.org

In March 1974, following a student demonstration in Patna against the Bihar Government and Assembly that resulted in widespread arson and looting and several deaths, Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) the leader of the Socialist Party and former Gandhi supporter, accepted an invitation from the student leaders to give guidance and direction to their movement. As he was to declare in a speech to these students, ‘After 27 years of freedom, people of this country are wracked by hunger, rising prices, corruption… oppressed by every kind of injustice… it is a Total Revolution and we want nothing less!’

His immediate purpose was to ensure that the developing agitation would be peaceful and nonviolent but, in accepting the invitation, he set in motion a train of events which included not merely splitting the Sarvodaya movement of which he was the most prominent leader after Vinoba Bhave but also, and more importantly, polarising all the major political parties and forces in India. Fifteen months later, this polarisation led to a head-on confrontation between the Opposition parties and the Central Congress Government (supported by the Communist Party of India), the outcome of which was the declaration of a state of emergency on 26th June 1975.

Read the rest of this article »

by Beverly Woodward

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished 1972 essay by Beverly Woodward is the latest in our series of discoveries from research that we are conducting in the IISG, Amsterdam. Please see the notes at the end for further details, references, acknowledgments, biographical information, and a link to the pdf file of the original. JG

The existing state of international disorder is often referred to as a state of global anarchy. The time honored human remedy for such a state of affairs is the establishment of the rule of law. Thus the remedy for the existing situation is often held to be the creation of more and better international law along with the creation of the institutions customarily associated with the presence of law, i.e., institutions for making, interpreting, and enforcing law. But there are many who are not enthused by the proposal. They include those national elites who speak piously of “law and order” at home, but are definitely less reverent when it becomes a question of forms of law that might be less supportive of their (self-defined) “interests” than the legal structures that they are so anxious to see upheld. They include the anarchists who insist that the current perversions in human behavior are not due to too little law, but to too much law, pointing out, for example, that it is governments that have authorized the great majority of the more brutal and massively destructive acts witnessed in this century. And they include many “ordinary people” who are neither opposed to law in general nor especially privileged by the given arrangements, but who are apprehensive of law formulated at such a great distance from its potential points of application. Even to those not inclined to rail against government wherever it occurs, “world government” or anything similar may seem a rather frightening remedy for what ails us.

Read the rest of this article »

by Devi Prasad

Schoolchildren dressing as Gandhi to commemorate his 146th birthday; courtesy newindianexpress.com

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished essay by Devi Prasad is another in our series from the IISG archive, Amsterdam. It is well to bear in mind that Prasad lived as a child at Tagore’s school, discussed in the article, and that he was later asked by Gandhi to teach in one of his ashrams. His knowledge of Gandhi’s education system, therefore, was uniquely first-hand. Please consult the notes at the end for archival reference, acknowledgments, and biographical information. JG

At the centre of Gandhi’s many concerns about social and political issues, there are two things that remained consistently predominant throughout his life. Firstly, a revolt against the education system that was given to, nay, imposed upon India by the colonial rule; and secondly, a powerful urge to find an appropriate approach and method of imparting education to all the children and adults of the country.

Read the rest of this article »

by Devi Prasad

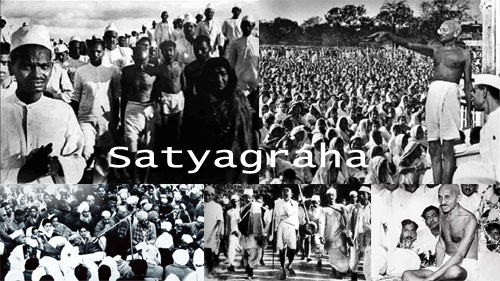

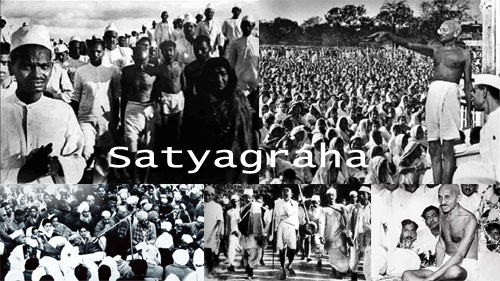

Gandhian civil resistance poster; courtesy peacetopia.com

To begin with I shall discuss some of the commonly used terms in connection with nonviolent action against oppression, and which are often mistakenly understood to be the same as the Satyagraha practiced and advocated by Gandhi. This is to try to point out the differences between the concepts these terms represent and how they are not quite the same as the concept of Satyagraha. These terms are passive resistance, non-cooperation, direct action, civil disobedience and non-resistance. My aim is not to minimise, even to the slightest degree, the merits, uses and strength of these methods, but to point out that in contrast to any of them Satyagraha is a complete philosophy, as well as the technique of fundamental social change. Whereas the philosophy of Satyagraha implies a holistic approach to both long term as well as immediate issues facing humankind, the practice of the above-mentioned concepts is, by definition, limited to particular situations without being necessarily related to other social or political problems.

Read the rest of this article »