Dan Berrigan in Rochester

by Dorothy Day

Editor’s Preface: During the Vietnam War there was a debate within the pacifist and nonviolent movements about tactics, brilliantly discussed in a recent book by Shawn Francis Peters on the Catonsville Nine. [1] The Nine had made their own napalm to destroy draft files and this, and a previous protest by the Berrigans, set off a string of similar actions in which burning, pouring of blood, and various other “symbolic” means were used to destroy files. As Peters book points out Dorothy was at first hesitant about criticizing the tactic, but as the debate spread through the pacifist and nonviolent movements, despite or because of her friendship with both Phil and Dan Berrigan she took a firm nonviolent stand against the destruction of property not one’s own, which follows here. JG

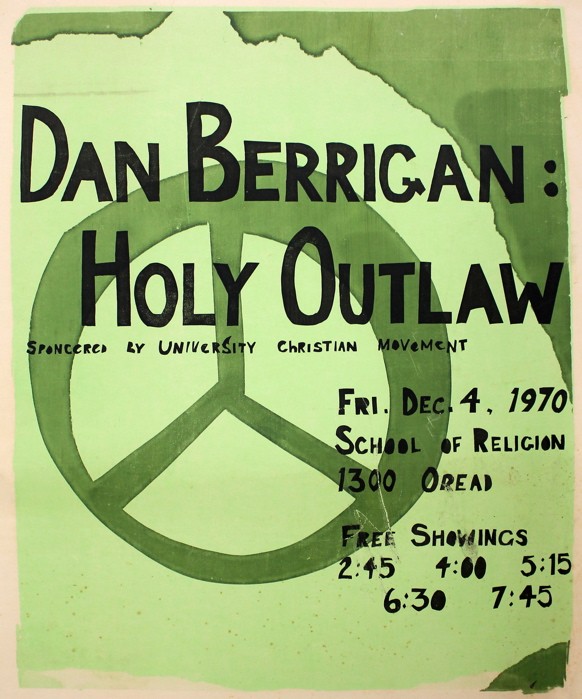

Poster for showing of a film; Univ. of Kansas at Lawrence; artist unknown

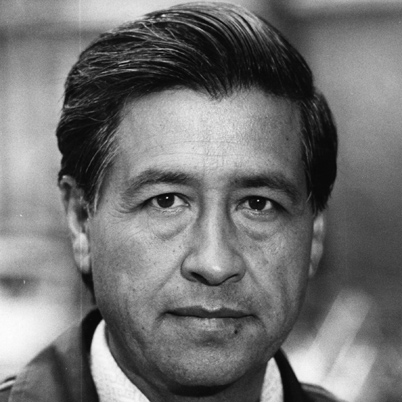

Crying out in behalf of the jail population of this country which is by and large made up of blacks, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, poor black and poor whites, in other words the poorest of the poor, Fr. Dan Berrigan has been heard from during this last month when he was called as a witness for one of the Rochester group, who are the latest to destroy draft files in government offices. [2] This group is one of the first to refuse lawyers (who must be paid sooner or later) except for one defendant who engaged only one – we presume, in order to call as character witness Fr. Berrigan from his prison cell in Danbury, Connecticut, where he is serving a long sentence with his brother Phil Berrigan, Josephite Father (dedicated to work among the blacks).

Fr. Berrigan was brought in chains to this upper New York State city where he was a character witness for Joe Gilchrist, one of the group. For some reason it took three days to transport him from Connecticut to New York State! He complained of the brutal and inhuman treatment he had received in transit. He testified also for all the prison poor in his protest.

The other defendants are remarkable in a number of ways. Two of them, Suzie Williams and DeCourcy Squires, refused bail and spent their time in prison awaiting trial. The others all showed up, not jumping bail and failing to appear as did some of those who have taken part in these actions of destruction of property.