by Terry Messman

“The destruction of creation and its creatures is done in the name of profit, convenience, and wealth. The truth is that capitalism is poison, and we are its victims.” Shelley Douglass

The path of nonviolence is a lifelong journey that leads in unexpected directions to far-distant destinations. One of the most meaningful milestones on Shelley Douglass’s path of nonviolence came on Ash Wednesday, Feb. 16, 1983, when she walked down the railroad tracks into the Bangor naval base with Karol Schulkin and Mary Grondin from the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action.

As the three women walked down the tracks used to transport nuclear warheads and missile motors into the naval base, they posted photographs of the atomic bomb victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — a prophetic warning of the catastrophic consequences of Trident nuclear submarines. The photos revealed the human face of war, the face of defenseless civilians struck down in a nuclear holocaust. The women continued on this pilgrimage deep into the heart of the Trident base, until security officers arrested them an hour after they began.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Shelley Douglass (left with microphone) speaking out against the deaths of children caused by U.S. sanctions in Iraq; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“The whole point of the arms race is to protect what we have that really isn’t justifiably ours. As long as we remain complicit with that, then to that extent we’re complicit with weapons like the Trident. So we were trying to withdraw our cooperation as much as we could.” Shelley Douglass

Street Spirit: You’ve devoted many years of your life to nonviolent resistance to nuclear weapons. When did you first become involved in the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action?

Shelley Douglass: The Pacific Life Community was the original group that started the Trident campaign. The crucial thing about it was that the whistle was blown on the Trident by the man that was designing it, Robert Aldridge. Jim and I had met Bob Aldridge when we were in the middle of the Hickham trial in Honolulu. [Editor: Jim Douglass, Jim Albertini and Chuck Julie were on trial for an act of civil disobedience at Hickam Air Force Base in protest of the Vietnam War. TM]

We didn’t know very much about Bob Aldridge until he came to visit us at our home in Hedley, British Columbia, several years later. He told us a very moving story about how he had spent his life designing nuclear weapons, and he and his whole family had made the decision that he should resign from his job for reasons of conscience. They had taken a tremendous cut in income. They had 10 kids, and his wife had gone back to work, and the whole family was behind this decision.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

“You age and die on death row if they don’t electrocute you or murder you in some other way. One of the men had a stroke and had to be taken care of. Leroy was one of the major caregivers for him. Leroy was never an angel, but he became a very compassionate person.” Shelley Douglass

Poster art courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Street Spirit: You described in Part 1 how you first became inspired by the Catholic Worker while in college. How did you begin Mary’s House in Birmingham?

Shelley Douglass: When we moved here to Birmingham, we were sort of delegated by Ground Zero to watch trains, but after we had been here for two years we realized there were no more trains to watch. So we had to make the choice: Do we go back to Ground Zero, or do we stay here, and if we stay here, what are we here for? That just kind of fit in with my always having wanted to do a Catholic Worker. So we decided that we would do a Catholic Worker, even though we had no money. I mean, you never have any money when you start a Catholic Worker.

Spirit: Dorothy Day described one of the primary missions of the Catholic Worker as providing houses of hospitality. Does Mary’s House offer hospitality?

Douglass: Well, physically, Mary’s House is a big old house, kind of like many Catholic Worker houses. It was built in 1920 in the Ensley area of Birmingham, which used to be a big steel and brick making area. It’s got four bedrooms, one of which I sleep in, and three of them we use as hospitality, primarily for families or single women. People come and stay while they get on their feet. It’s kind of like a big family house.

Read the rest of this article »

by Melanie Nakashian

St. Mary’s church, Iqrit; courtesy wagingnonviolence.org

Editor’s Preface: The story of the decades-long nonviolent protest in the village of Iqrit, northern Israel, is one we have previously covered, and can be found at this link. Indeed, our previous article, from our WRI research project, was written in 1974, to cover a nonviolent protest that had already been going on for several years. That the inhabitants have resorted to the courts and symbolic acts of protest such as planting trees and gardens, but have remained nonviolent, is one of the more remarkable stories of contemporary nonviolent protest. JG

Among the hundreds of Palestinian villages that were evacuated between 1947 and 1951, there is one whose descendants are actually getting close to fulfilling their right of return. In an unprecedented case, the demolished Christian village of Iqrit should soon be connected to Israel’s electricity grid. This comes just as a group of Iqrit’s young descendants mark three years, this August 5 [2015], of continuously inhabiting the church in their otherwise destroyed village.

Read the rest of this article »

by Barbara Deming

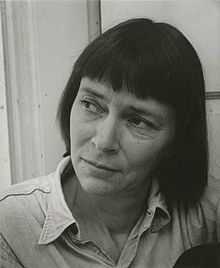

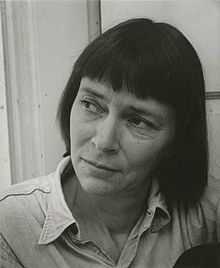

Portrait of Deming c. 1960s, courtesy demingfund.org

Editor’s Preface: Barbara Deming (1917-1984) was a lesbian/feminist activist and proponent of nonviolent social change, her most notable work being Revolution and Equilibrium (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971). A foundation has been set up in her name to give financial support to women’s causes. Their website has further biographical information. This article is taken from War Resistance: Journal of the War Resisters, issue 39, fourth quarter, 1971. Please also see the archive reference information and acknowledgments at the end. JG

I have been asked to write about the relation between war resistance and resistance to injustice. There are many points to be made that I need hardly labor. I don’t have to argue at this date that if we resist war we must look to the causes of war, and try to end them. And that one finds the causes of war in any society that encourages not fellowship but domination of one person by another. We must resist whatever gives encouragement to the will to dominate.

I don’t think you would object to my stating the relationship between the two struggles in another way; restating it, for it has been often said: Bullets and bombs are not the only means by which people are killed. If a society denies to certain of its members food or medical attention, or a political voice, the sense of their own worth, the freedom to exercise their talents — this, too, is waging war of a kind.

Read the rest of this article »

by Joan V. Bondurant

Jacket art courtesy Princeton University Press

Every leader who seeks to win a battle without violence and who presumes to precipitate a war against conventional attitudes and arrangements, however prejudiced they may be, would do well to probe the subtleties distinguishing satyagraha from other forms of action also claiming to be nonviolent. There are essential elements in Gandhian satyagraha which do not readily meet the eye. The readiness with which Gandhi’s name is invoked and the self-satisfaction with which leaders of movements throughout the world make reference to Gandhian methods are not always backed by an understanding of either the subtleties or the basic principles of satyagraha. It is important to pose a question and to state a challenge to those who believe that they know how a Gandhian movement is to be conducted. For nonviolence alone is weak, non-cooperation in itself could lead to defeat, and civil disobedience without creative action may end in alienation. How, then, does satyagraha differ from other approaches? This question can be explored by contrasting satyagraha with concepts of passive resistance defined by the Indian word duragraha.

Duragraha means prejudgment. Perhaps better than any other single word, it connotes the attributes of passive resistance. Duragraha may be said to be stubborn resistance in a cause, or willfulness. The distinctions between duragraha and satyagraha, when these words are used to designate concepts of direct social action, are to be found in each of the major facets of such action. (1) Let us examine: (a) the character of the objective for which the action is undertaken; (b) the process through which the objective is expected to be secured, and (c) the styles which characterize the respective approaches. Satyagraha and duragraha are compared below in each of these three aspects by considering their relative treatment of first, pressure and persuasion, and second, guilt and responsibility. Finally, we shall have a look at the meaning and limitations of symbolic violence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Asha Devi Aryanayakam

Editor’s Preface: This article is taken from The War Resister, issue 92, Third Quarter 1961. We have posted a number of other articles on Shanti Sena, which may be accessed via our search function. Notes about the author, references, and acknowledgments are found at the end. JG

“Soldiers Painting Peace”; mural by Banksy; courtesy stencilrevolution.com

The conception of a Peace Brigade or a Peace Army was first placed before the Indian people by Gandhi in 1938. He was then engaged in the great experiment of reconstructing Indian national life through nonviolence. The movement for political independence was only a part of the story. The monster of communal tension had just begun to rear its ugly head and the Peace Army was Gandhi’s answer to the problem. With his characteristic straightforwardness, he placed his proposal in down-to-earth practical terms without any philosophical introduction.

As he wrote, ‘Some time ago I suggested the formation of a Peace Brigade (Shanti Sena), whose members would risk their lives in dealing with riots, especially communal. The idea was that this brigade should substitute for the police and even the military. This sounds ambitious. The achievement may prove impossible.’

Gandhi then suggested qualifications for the volunteers, which are mentioned by Donald Groom in his contribution to this issue of the War Resister [posted below under this date]. As Gandhi wrote, ‘Let no one understand from the foregoing that a nonviolent army is open only to those who strictly enforce in their lives all the implications of nonviolence. It is open to all those who accept the implications and make an ever increasing endeavour to observe them. There never will be an army of perfectly nonviolent people. It will be formed of those who will honestly endeavour to observe nonviolence.’ (Harijan, 21.7.1940.)

Read the rest of this article »

by Dr. Susan S. Bean

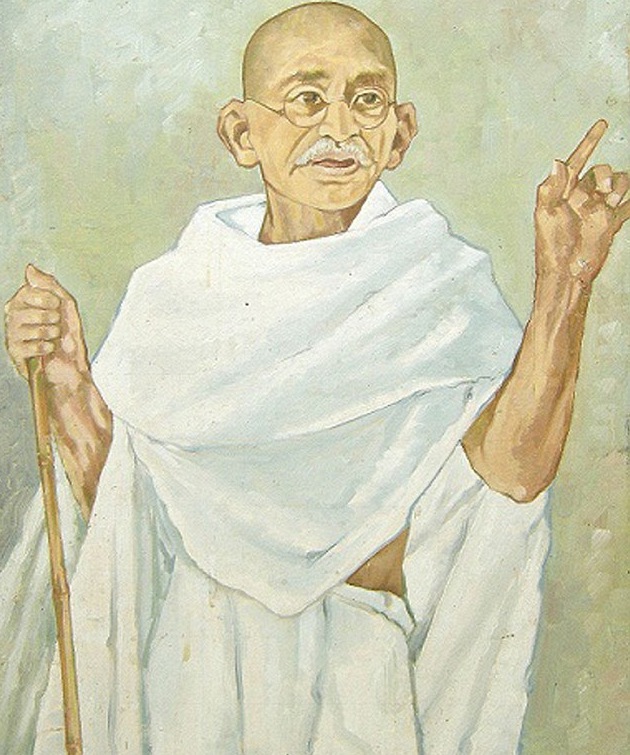

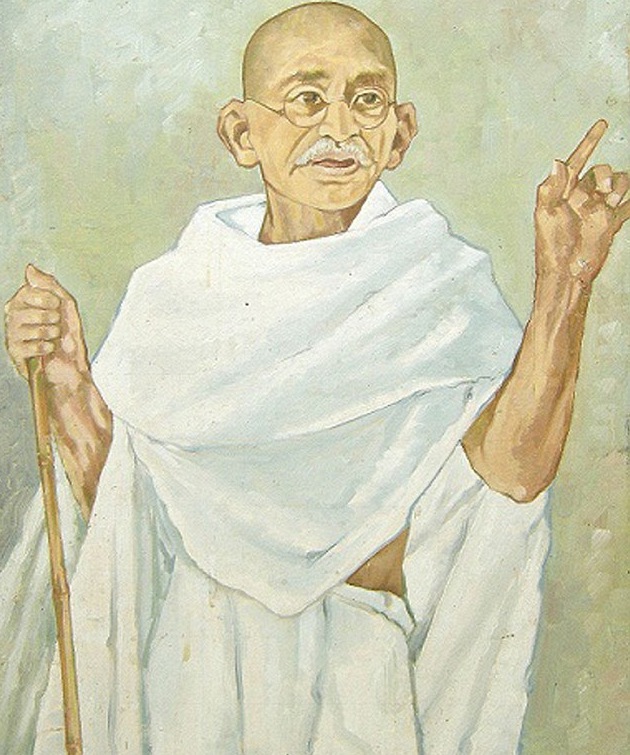

Painting of Gandhi, c. 1945, by J. L. Bhandari; courtesy dailymail.co.uk

Prologue: The story of khadi (homespun) and its creator Mohandas Gandhi is well known in India and around the world. In his political campaign for Indian self-determination (swaraj), Gandhi famously promoted the practices of making thread through spinning by hand, and wearing simple khadi garments – not only as key symbols of national identity, but also as a central statement of resistance to the colonial regime. As writer, producer and director, Gandhi instigated a national drama centred on the roles of spinner and khadi-wearer. Made from hand-spun yarn, his khadi would emerge from India’s handlooms not just to costume the nation but also to change the essential character of its people, altering colonial subjects into ‘citizens’. Seen as theatre, the narrative of khadi reveals how Gandhi transformed this cloth into much more than a mere textile, and how khadi exerted transformative and long lasting effects in India’s national movement. The drama of khadi illuminates the potency and tenacity inherent in this humble homespun cloth; already having proved itself within the framework of the freedom struggle, the story of khadi still resonates more than sixty years after India gained Independence. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Claire Gorfinkel and Howard Frederick

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished article details the 1974 visit by the authors to the Palestinian villages of Kafr Bir’im and Iqrit, in Israel 4 kilometres south of the Lebanese border. Most of the inhabitants had been expelled in 1948 during an Israeli military campaign against the Arab Liberation Army and Syrian forces, Operation Hiram. A few stalwart villagers remained to protect their ancestral homes, and the article vividly details their struggle. A small Malkite Greek Catholic church was also kept open in Iqrit and crops planted in both villages, every year uprooted by Israeli settlers or army. The authors met with the Malkite Archbishop Joseph Raya (1916-2005), who was one of the leaders of a joint Palestinian-Israeli nonviolent peace effort. In 1965 he had also been made Grand Archimandrite of Jerusalem. Further textual and biographical notes appear at the end of the article. JG

Ruins of Kafr Bir’im; courtesy wikipedia.org

Kafr Bir’im and Iqrit are Arab Christian villages, located in Israel just south of the Lebanese border. The villagers’ story is a simple one. Israeli Jews and Arabs have verified its authenticity. Prior to the 1948 war the inhabitants of Kafr Bir’im and Iqrit had good relations with their Jewish neighbours. (1) They had helped illegal Jewish immigrants cross the Lebanese border, and they welcomed the new Jewish state. The fighting never directly involved the villages, and when the Israeli army arrived at the end of October 1948, the villagers, unlike many Arab Palestinians, did not resist or flee. Based on their long friendship with Jews, they welcomed the Army with traditional bread and salt.

Two weeks later, the army asked the villagers to leave their homes for a short time. Chroniclers have disputed the reasons for this request. Some say that an Arab counter-offensive from Lebanon was anticipated, but others say that was only a pretext to get them off their land. In any case, the villagers were assured that they would be allowed to return in a fortnight. Today, twenty-six years later, these loyal citizens of Israel are still denied permission to live in their ancestral homes. Their campaign to regain their land has been a classic nonviolent struggle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Metta Spencer

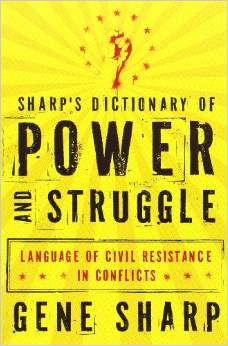

Book jacket courtesy Oxford University Press; global.oup.com

Metta Spencer: It has been eight years since I last interviewed you for the magazine. Since then people around the world have begun to listen to you.

Gene Sharp: Yes, I was just now invited to a Washington journal — Foreign Policy — who will publish something about people who had some response in the world in the last year. That kind of invitation never happened a few years ago.

Spencer: I know. In fact, let’s begin by reviewing the changes in your own thinking. As I recall, you started off as a graduate student in sociology working on a masters thesis and have managed to turn into Gene Sharp, the guy on the front page of the New York Times. Let’s start at the time when you began to realize that nonviolence was a special set of practices that could be developed into useful procedures.

Sharp: Ah yes! One thing that was in the master’s thesis was a typology of nonviolence. I classified six or seven belief systems, of which one was called “nonviolent resistance.” That’s a different category but it was in with the others. (Today I don’t even like the term “nonviolence” except for very special uses.) That typology went through several revisions and one was published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, which was an entirely new publication at the time. In it I took out nonviolent struggle as a separate category. That was a breakthrough in my thinking — that people didn’t have to have the belief in order for them to act.

I remember one time in the basement of the Ohio State University library. I was looking through old Indian newspapers on the conflict — I think it was the 1930 campaign — and the evidence was there: These people did not believe in nonviolence as an ethic! That was a shock. I thought: Oh dear! We didn’t have copy machines then. I had to copy the whole thing by hand and I thought; should I copy that down? It’s not supposed to be that way. But my focus on reality won out, fortunately, and I copied it down. Later I realized that it wasn’t a problem. It was a breakthrough, an opening! People didn’t have to believe in order to use this form of action! Therefore, it was open to almost everybody. That breakthrough was in about 1950 or ’51.

Read the rest of this article »