by Dana Greene

Dustwrapper art courtesy Scribner; simonandschusterpublishing.com/scribner

Who was Dorothy Day? In his address to Congress, Pope Francis named her an American icon of the stature of Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr., and New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan is among those moving her case forward for canonization. There are abundant materials documenting Day’s life and contributions — her autobiographies, letters, diaries, hundreds of her Catholic Worker columns, and a spate of biographies by Robert Coles, Jim Forest, William Miller and others.

One might ask whether another biographical venture, this one written by Day’s youngest granddaughter, might be redundant or sentimental? It is neither. Kate Hennessy’s biography, Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty; An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother (New York: Scribner, 2017) offers valuable insights into understanding this “complex,” “restless,” “bullheaded,” “judgmental” and “contradictory” woman who in her life railed against being referred to as a saint. It is a clear-eyed, tough but tender telling of Day’s life that goes far in saving her from the hagiographic “embalming” that so often accompanies saint-making.

Hennessy’s “insider” story is unique, a family biography linking Day with her daughter, Tamar, and Day’s nine grandchildren, most prominently Hennessy herself. It opens with the story of Day’s early life, her sense of not belonging, and then the Bohemian years of this “Northern Communist whore” in the 1920s and 30s.

Read the rest of this article »

by Helen Fox

Teaching Peace illustration courtesy johnworldpeace.com

Abstract: In-depth interviews with undergraduates at a high-ranking, politically liberal U.S. university suggest that young adults who are most likely to occupy future positions of influence are skeptical of the idea that a world without war is possible. Despite their aversion to war in general and the Iraq War (also called The Second Gulf War: 2003-2011) in particular, these students nearly always said they believe that war is an integral part of human nature and that peaceful international relations will always be subverted by individuals and/or groups that insist on taking advantage of others. When students defended the need for war, they did not cite international terrorism or self defense as just causes, but rather the responsibility to protect defenseless others such as villagers in Darfur or Jews in Hitler’s Germany. However, students knew little about the prevalence and efficacy of nonviolent movements or the range of diplomatic and political tactics that have been employed to deter violence. The author shares the content and methods of her seminar on nonviolence, and concludes that more courses in secondary schools and universities need to fill the gaps in students’ knowledge by teaching historical, social, political, and psychological information about both war and peaceful solutions to conflict.

Read the rest of this article »

by E. S. Reddy

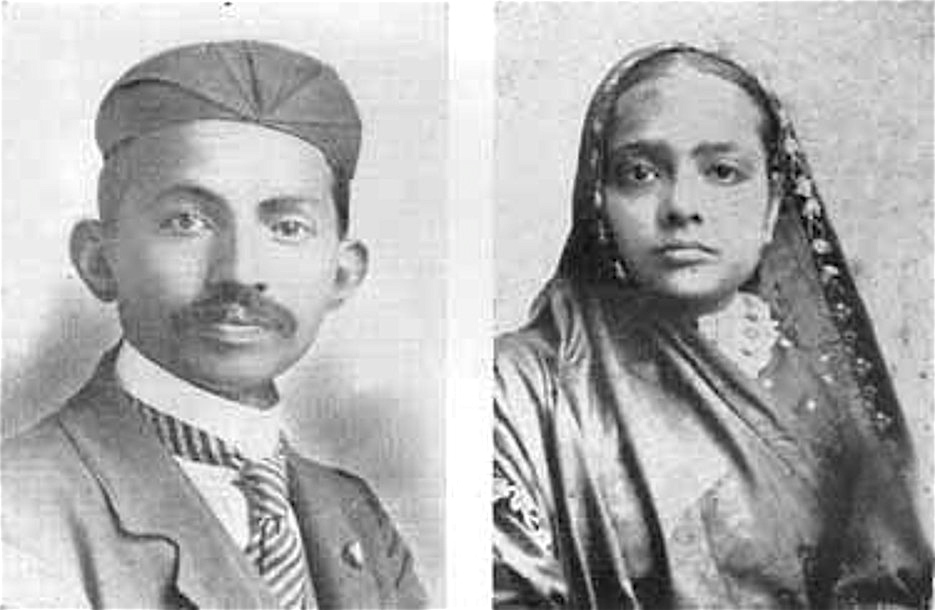

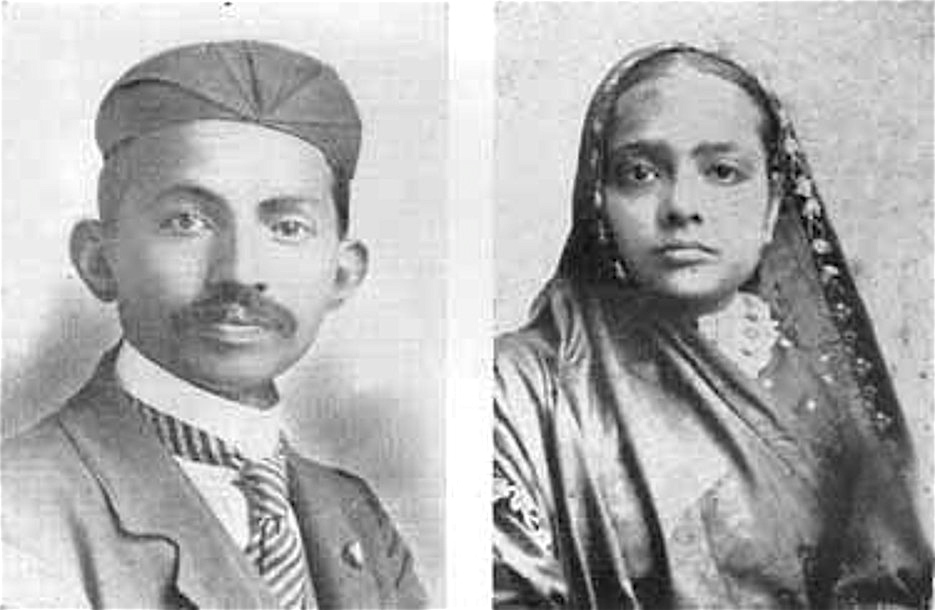

Portraits of Mohandas and Kasturba Gandhi at the time of the South African campaign; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Editor’s Preface: We have posted several articles on significant figures in the Satyagraha movement, other than Mahatma Gandhi. We have also featured articles on women nonviolence leaders such as Vandana Shiva and Dorothy Day. This article concentrates on the role Gandhi’s wife, Kasturba Gandhi (1869–1944), played in the South African satyagraha campaign. Please also see the note at the end for biographical information about the author, and acknowledgments. JG

Kasturba Gandhi by her “silent suffering” as a prisoner sentenced in 1913 to three months rigorous imprisonment, made a crucial contribution to the success of the nonviolence civil resistance campaign (satyagraha) in South Africa, but this is little known.

In early 1913, when satyagraha in the Transvaal had been suspended, Justice Malcolm Searle of the Cape Supreme Court ruled that marriages performed according to a religion which allowed polygamy – that is, all Muslim and Hindu marriages – would not be recognised in South Africa. If this ruling had prevailed, almost all married Indian women would have been reduced legally to the status of concubines and their children treated as illegitimate. The women and children would have lost the right of inheritance and the right to enter South Africa. The government ignored repeated appeals from the community for legislation to remedy the situation.

Read the rest of this article »

by Beverly Woodward

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished 1972 essay by Beverly Woodward is the latest in our series of discoveries from research that we are conducting in the IISG, Amsterdam. Please see the notes at the end for further details, references, acknowledgments, biographical information, and a link to the pdf file of the original. JG

The existing state of international disorder is often referred to as a state of global anarchy. The time honored human remedy for such a state of affairs is the establishment of the rule of law. Thus the remedy for the existing situation is often held to be the creation of more and better international law along with the creation of the institutions customarily associated with the presence of law, i.e., institutions for making, interpreting, and enforcing law. But there are many who are not enthused by the proposal. They include those national elites who speak piously of “law and order” at home, but are definitely less reverent when it becomes a question of forms of law that might be less supportive of their (self-defined) “interests” than the legal structures that they are so anxious to see upheld. They include the anarchists who insist that the current perversions in human behavior are not due to too little law, but to too much law, pointing out, for example, that it is governments that have authorized the great majority of the more brutal and massively destructive acts witnessed in this century. And they include many “ordinary people” who are neither opposed to law in general nor especially privileged by the given arrangements, but who are apprehensive of law formulated at such a great distance from its potential points of application. Even to those not inclined to rail against government wherever it occurs, “world government” or anything similar may seem a rather frightening remedy for what ails us.

Read the rest of this article »

by Sita Kapadia

M. K. Gandhi and wife, Kasturba, 1902; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Mahatma Gandhi’s legacy to the world is immeasurable; his life and work have left an impact on every aspect of life in India; he has addressed many personal, social and political issues; his collected works number more than one hundred volumes. From these I have gleaned only a few thoughts about women and social change.

In 1940, reviewing his twenty-five years of work in India concerning women’s role in society, he says, “My contribution to the great problem lies in my presenting for acceptance truth and ahimsa (nonviolence) in every walk of life, whether for individuals or nations. I have hugged the hope that in this woman will be the unquestioned leader and, having thus found her place in human evolution, will shed her inferiority complex … Woman is the incarnation of ahimsa. Ahimsa means infinite love, which again means infinite capacity for suffering. And who but woman, the mother of man, shows this capacity in the largest measure? … Let her translate that love to the whole of humanity … And she will occupy her proud position by the side of man … She can become the leader in satyagraha.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Rev. Nichiko Niwano

Portrait of Ela Ramesh Bhatt courtesy www.npf.or.jp/english

Editor’s Preface: This interview was conducted upon the award of the 2010 Niwano Peace Prize to Ela Ramesh Bhatt, founder of the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), an Indian women’s labor union with more than 1.2 million members. She was cited for having worked for “more than thirty years to improve the lives of the poorest and most oppressed women workers.” Rev. Nichiko Niwano is president of the Niwano Peace Foundation in Tokyo, which manages the prize. Please consult the note at the end for further biographical information, acknowledgments, and links. JG

Niwano: I have been particularly impressed by the fact that your activities promoting self-reliance for female workers are based on the spirit of nonviolence. Efforts for social reform always arouse opposition. If we look at history, there have been a great many confrontations wherein “blood washes blood” in cycles of violence. At present, violence swirls around the world. I think that within this context, your work clears a new pathway to the future. Furthermore, you do not view women simply as “the weaker sex”. You have said that “women are the key to the formation of society” and that “women must become the leaders of social change”. These are extremely important messages as we consider the future. Although I am meeting you for the first time, I have very much looked forward to having this dialogue with you, and it is a great pleasure to greet you.

Bhatt: First of all, thank you very much, and I’m really very pleased and grateful that the Niwano Peace Prize of Japan has recognized the courage and the hard work of my SEWA sisters in India. They are trying to build a peaceful society based on constructive work. Personally, the prize is humbling, and makes me more conscious of the immensity of the challenges before us. I realize that life is short and art is long.

Read the rest of this article »

by Sean Chabot

Dust jacket courtesy Oxford University Press; global.oup.com

In her preface to the 1965 edition of Conquest of Violence (see References at the end), Joan Bondurant makes a strong case for distinguishing nonviolent action as duragraha or Gandhian satyagraha. She argues that duragraha involves pressuring opponents based on a de facto prejudgment that they are wrong, through passive resistance, and through symbolic violence. In a later essay (posted previously here), she adds that it is a form of stubborn or willful resistance seeking to demonstrate that opponents are necessarily wrong; that resisters are inherently righteous; and that the purpose of nonviolent action is to gain predetermined objectives by winning battles with opponents. In contrast to satyagraha (i.e., firmness in seeking truth through the power of love), duragraha aims at gaining tangible concessions from power-holders in the short-term rather than transforming social relationships and creating in the long run alternative ways of life benefiting everyone, especially the most oppressed. Bondurant emphasizes these distinctions, because she feels that most of the so-called Gandhian struggles during the 1960s are actually examples of duragraha, not satyagraha. In her eyes, this misunderstanding severely limits the political, ethical, and transformative potential of these struggles.

In the 1960s, Gene Sharp—the undisputed pioneer of nonviolent action and civil resistance studies—responded very differently to Gandhi’s legacy. Unlike Bondurant, Sharp invokes Gandhi to define nonviolent action as “a technique used to control, combat and destroy the opponent’s power by nonviolent means of wielding power”, without carefully conceptualizing satyagraha or considering how it diverges from duragraha (Sharp 1973: 4). By erasing these differences, and by focusing on conventional power politics instead of situational ethics, his The Politics of Nonviolent Action articulates a generic and simplistic understanding of nonviolent action that applies to many cases of unarmed resistance throughout history and across the world. In the process, he normalizes duragraha as a pragmatic and strategic form of nonviolence, thereby hollowing out Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha while continuing to use Gandhi’s name to popularize his own approach. Since the 1970s, Sharp has quickly become the most influential figure in the field, serving as mentor to fellow civil resistance authors like George Lakey, Peter Ackerman, Jack Duvall, Michael Randle, Howard Clark, April Carter, and of course Mary King.

Read the rest of this article »

by Hildegard Goss-Mayr

Brazilian farmers’ nonviolent land protest; courtesy mettacenter.org

Editor’s Preface: The following, previously unpublished essay was presented to the Alternative Defense Commission, as part of the War Resisters’ International Peace Education Project, c. 1987. It continues our series of discoveries from the WRI archive. Please see the notes at the end for archival reference, as well as acknowledgment and biographical information about the author. JG

In most Latin American countries military or civilian dictatorships, on the basis of the doctrine of national security, continue to uphold an economic system of exploitation that favors a small group of privileged individuals (as well as national and multinational corporations in the First World) and condemns the vast majority of the people to a life of dependence, misery, and political and social marginalization. But the masses of the poor in Latin America have increasingly become aware of their human rights and dignity, and in many parts of the continent, despite violent and brutal repression, they have begun to organize and struggle for change. Popular civic movements are springing up and pressing for justice.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

“The feminism that I believe in is a defense of all life. Not only women, not only the earth, but all together. It’s all reweaving the web.” Shelley Douglass

Jim and Shelley Douglass demonstrating for peace in Birmingham, Alabama.

Street Spirit: Concern for the rights of women, both in society and in the peace movement, was always a part of Ground Zero’s message to the larger movement. Can you describe how feminism and women’s issues became interwoven with Ground Zero’s peace work?

Shelley Douglass: Well, you have to remember that Ground Zero — and Pacific Life Community, which preceded it — were founded on the idea that nonviolence was a way of life. So it wasn’t just a political type of resistance campaign against Trident. It was an attempt, and is an attempt, to learn a new way of living where things like Trident are not necessary any more. In order to do that, you have to have justice, because the point of the weaponry is to defend things that are unjust or structures that are unjust. So equal rights for women was part of the basis of what we were doing.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Jim and Shelley Douglass with Seattle Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, c. 1980; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Street Spirit: I just read John McCoy’s new biography of Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, A Still and Quiet Conscience [Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2015]. He is such an inspiring man, but it was shocking to learn about the horrible indignities he suffered for speaking out for peace. Could you describe your impressions of the archbishop when he came to peace demonstrations at Ground Zero?

Shelley Douglass: He’s the kind of person you would never think was an archbishop, you know. You would never think of him as an archbishop or anybody with any power. I mean he’s just this guy, not particularly well dressed. When we knew him, he just seemed like this old guy and he was bald and had kind of a kindly persona. He listened a lot, and didn’t do a lot of talking.

I think that the first time I met him I was in jail. We had gotten arrested for committing civil disobedience and Jim and one other person in our group were both doing a fast. I don’t remember why the archbishop came to visit us in jail, but people were concerned about Jim’s safety, basically. I don’t know who got him to come, but he came, and even though he didn’t look or act like an archbishop, because he was the archbishop, the jail gave him a special visit. And they put Jim in a wheelchair and wheeled him down, and there was the archbishop!

Read the rest of this article »