by Vladimir Tchertkoff

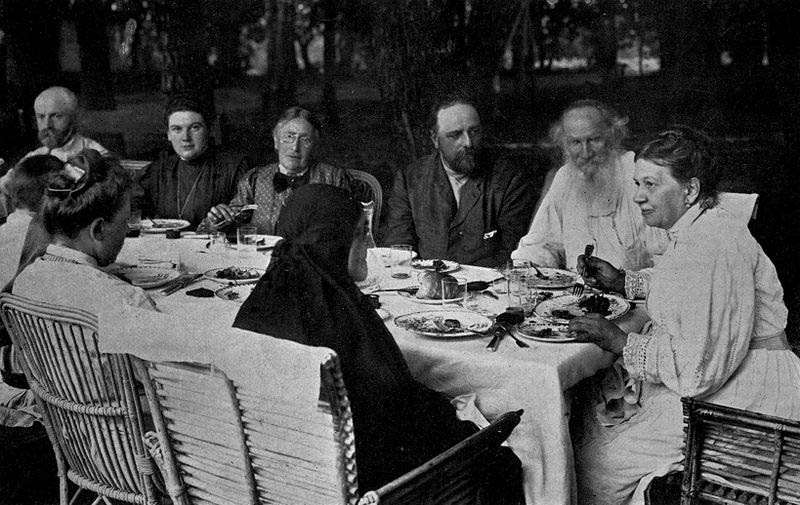

Tolstoy, 1905; photographer unknown; courtesy IISG/WRI

Editor’s Preface: The document that follows, Thoughts on Life, Death, Love, Non-Resistance, Religion, Revolution, Socialism, Communism, etc. is an unpublished English translation of selections from Tolstoy’s diaries between the years 1907-1908. The selection was made by Vladimir Tchertkoff (1854-1936), Tolstoy’s literary agent and the editor-in-chief of his collected works. The date of the selection is not mentioned, although the typescript bears a date of 1934 (see heading below). The translator is also unnamed. There is however an accompanying note by Tchertkoff, “How to translate Tolstoy”, addressed to his secretary Alexander Sirnis, who, together with Charles James Hogarth, was responsible for the translation of The Diaries of Leo Tolstoy: Youth 1847 to 1852, New York: Dutton, 1917. It is likely that Sirnis was responsible for this translation, and if so, it can be dated to between 1908 and 1918 (the death of Sirnis). This same note also mentions a Mrs. Mayo as providing corrections. Isabella Fyvie Mayo was an author who knew both Tolstoy and Gandhi, and had collaborated previously with Sirnis on several translations. If she was indeed responsible for the editing of the translation, the typescript must date to no later than 1914, the year of her death. In “How to translate Tolstoy” Tchertkoff insists that the translation be as literal as possible and must preserve the style and flavor of Tolstoy’s literary style and vocabulary. The phrasing is often quaint and differs radically from later translations of Tolstoy’s diaries, such as R.F. Christian’s Tolstoy’s Diaries, London: The Athlone Press, 1985. It is not clear whether Tchertkoff intended Thoughts as a “manifesto” for the flourishing Tolstoyan movement, of which he was a leader, or as an appendix to The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), in which Tolstoy argued that Christians had not sufficiently recognized that love for everyone also required that evil not be resisted by violence, particularly in the form of war or state sanctioned coercion. The insistence on the notion that God is love and the overriding importance of non-resistance are certainly two key elements of these Thoughts. Although Tchertkoff edited two volumes of Tolstoy’s diaries, The Diaries of Leo Tolstoy: Youth, 1847 to 1852, New York: Dutton, 1917; translated by C.J. Hogarth and A. Sirnis, and The Journal of Leo Tolstoy: First Volume, 1895 to 1899, New York: Knopf, 1917; translated by Rose Strunsky, the document that follows has never been published. It forms part of a larger collection of Tchertkoff and Tolstoy material that was donated in the early 1970s to the War Resisters’ International by the daughter of Ludvig Perno, a Tolstoy scholar and translator, and is part of the WRI archive at the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Further notes on the text and photographs are at the end of the transcript. A pdf scan of the original may be accessed by clicking on this link. Another pdf scan of the Perno acquisition letter can be accessed at this link. Gertjan Cobelens

Thoughts on Life, Death, Love, Non-Resistance, Religion,

Revolution, Socialism, Communism, etc.

Unpublished Diaries and Notebooks of Leo Tolstoy;

supplied by V. G. Tchertkoff, Box 1234, Moscow, USSR;

no rights reserved.

Copy of this was sent to Russia, 12-11-34.

Tolstoy in the woods at Yasnaya Polyana; photo by Vladimir Tchertkoff; courtesy IISG/WRI

Tolstoy’s Diaries and Notebooks

[No date. GC] How strange it must be to feel oneself alone in the world, separated from everything else. No matter how far he may have strayed from the path, a man would not be able to live if he did not feel his spiritual bond with the world, with God. If he loses the consciousness of this bond, he is unable to live and kills himself. This explains almost all the cases of suicide.

Read the rest of this article »