On Education

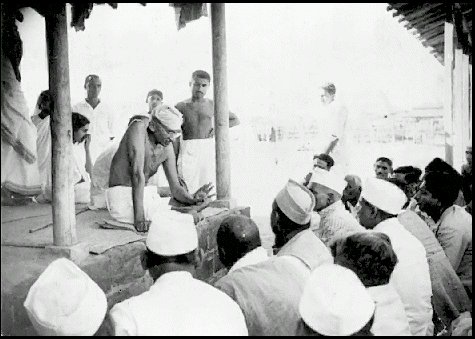

Gandhi teaching his followers; courtesy mkgandhi.org

Editor’s Preface: Gandhi highly valued education as an essential part of his nonviolence program, and insisted it be included in the daily life of the various ashrams that he founded. (1) If regular classes were held for children, adults were also asked to learn spinning, weaving, cloth making, and a host of other skills. It was not until 1909, however, that Gandhi began to systematize his thoughts, in the essay that follows. It is, in fact, Chapter 18 of one of his most important and influential works, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, presented as a series of questions and answers between the fictitious, if sometimes obtuse “Reader”, and answers by a knowing “Editor”, both of whom, needless to say are Gandhi. Hind Swaraj was written in a flurry of work between 13 and 22 November 1909 while Gandhi was on board the Kilnonan Castle sailing back from England to South Africa. Although he continued to write about education in Young India, Indian Opinion, and other of the periodicals he edited, the text that follows is recognized as his first attempt to outline the basics of a curriculum consisting of language, Indian civilization, and ethics. Please consult the notes at the end for further bibliographical information. JG

Reader: In the whole of our discussion, you have not demonstrated the necessity for education; we always complain of its absence among us. We notice a movement for compulsory education in our country. The Maharaja Gaekwar has introduced it in his territories. (2) Every eye is directed towards them. We bless the Maharaja for it. Is all this effort then of no use?

Editor: If we consider our civilization to be the highest, I have regretfully to say that much of the effort you have described is of no use. The motive of the Maharaja and other great leaders who have been working in this direction is perfectly pure. They, therefore, undoubtedly deserve great praise. But we cannot conceal from ourselves the result that is likely to flow from their effort. What is the meaning of education? It simply means knowledge of letters. It is merely an instrument, and an instrument may be well used or abused. The same instrument that may be used to cure a patient may be used to take his life, and so may knowledge of letters. We daily observe that many men abuse it and very few make good use of it; and if this is a correct statement, we have proved that more harm has been done by it than good. (3)