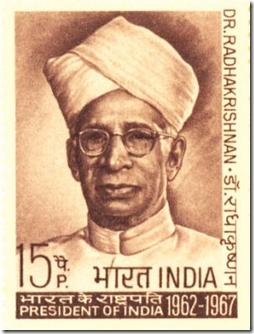

by Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Editor’s Preface: When Dr, Radhakrishnan wrote this essay in 1962 for the Gandhi National Memorial Fund, New Delhi he was the second President of India and one of India’s foremost contemporary philosophers. A relatively unknown essay, it is another in our series of discoveries from the War Resisters’ International archive. For an archival reference and biographical information about Dr. Radhakrishnan please see the notes at the end. JG

Indian commemorative postage stamp; courtesy librarykvpattom.wordpress.com

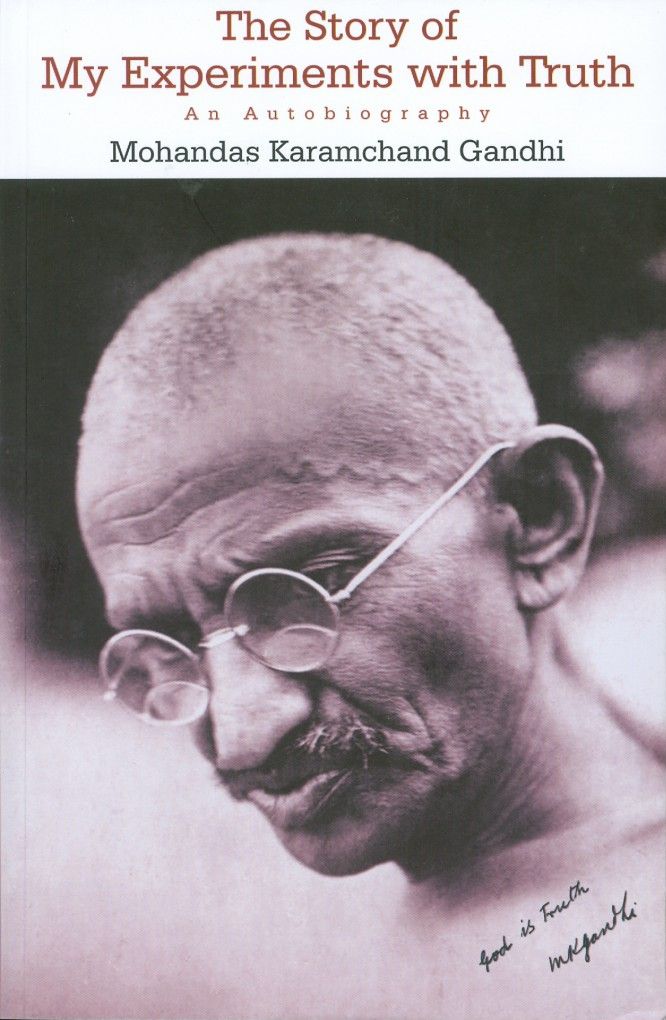

Many parts of the world are eagerly and enthusiastically awaiting the centenary of Gandhi [2 October 1969]. We here in India await it too. Though he belonged to the world, he also belongs to our country. As the London Times remarked: “No country other than India, and no religion other than Hinduism could have produced a Gandhi.” So he belongs to us in a very special sense. There are several ways in which he has worked for the country and the world. He was a great nationalist leader. He was a liberator of the enslaved. He taught the doctrine of a love that never fails. He was a moral genius who tried to chasten himself first before trying to exert any kind of influence on others. In all these ways he has helped us.

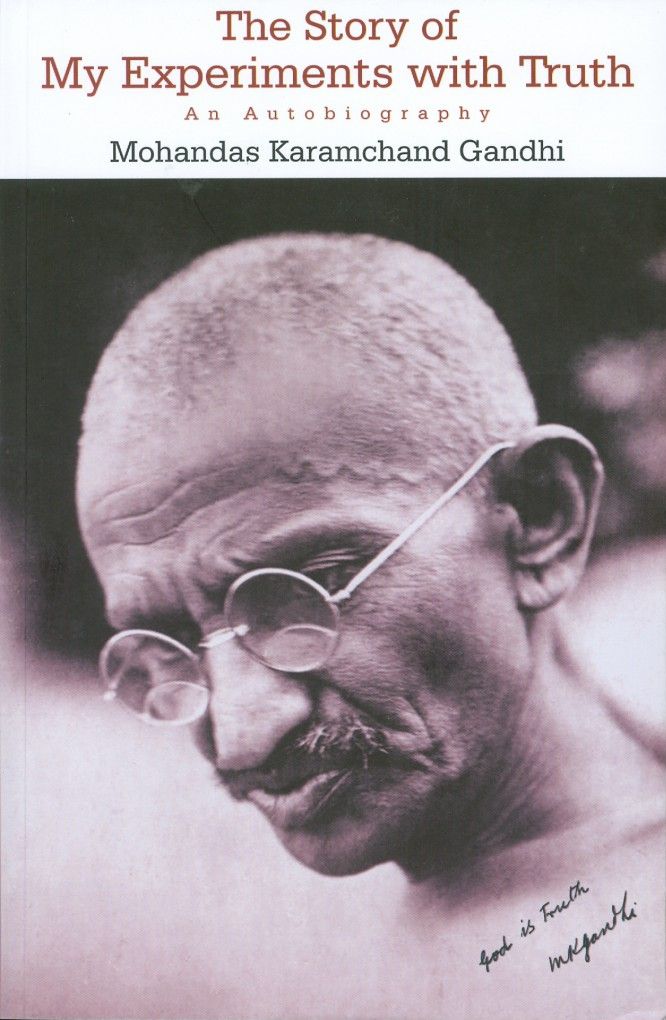

It is over thirty years ago that I put to Gandhi three questions: (1) What is your religion? (2) How are you led to it? (3) What is its bearing on life? He gave the following brief answers: “I used to say, ‘I believe in God’, now I say, ‘I believe in truth’. ‘God is truth’, that is what I am saying and today I say, ‘Truth is God’. There are people who deny God. There are no people who deny Truth. It is something which even the atheists admit.” Here he was not enunciating any new proposition. He was merely declaring fundamental truths that have come down to us from the environment in which he lived, the environment which nourished him. He took up two things. Speak the truth, do the right thing: truth and right action. He called them ‘Truth and Ahimsa’. These were his principles. Truth is not something we can casually work at. It requires considerable travail of the human spirit to cultivate harmony between the inward and the outward.

Read the rest of this article »

by Beverly Woodward

Nonviolence sculpture by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Editor’s Preface: This unpublished essay was presented at an international conference of peace researchers and activists (July 1-6, 1975, Noordwijkerhout, Netherlands), and continues our series of rediscoveries from the War Resisters’ International archive. For further notes on the text, the archival reference and a biographical note about Woodward please see the end. JG

The term “nonviolence” has been a controversial one. Over the years many have objected to it on the grounds that it is negative rather than positive in substance and therefore does not hold out a vision of what one is for rather than what one is against. The objection is valid, but it overlooks one benefit obtained by the use of this term. When we speak of nonviolence we highlight the fact that a peaceful world cannot be attained without struggle and resistance. Nonviolence is anti-violence and must be, since violence, unfortunately, is woven into the fabric of our lives. To obtain peace we must resist violence. To resist violence is to resist deeply rooted inclinations, habits, customs, laws, and institutions.

Read the rest of this article »

by Theodor Ebert

Editor’s Preface: This unpublished essay, by an eminent Christian pacifist and theorist, was a paper presented at the Study Conference on Nonviolent Solutions of Conflict with Special Reference to Germany and Berlin. It was held in Offenbach, Germany, in August 1964 under the joint auspices of War Resisters’ International, and is another in our series of rediscoveries from the WRI archive. Please see the notes at the end for further archival references and biographical information about the author. JG

Image courtesy vjai.com

In March 1964 a collection of articles was published in London under the title ‘Civilian Defence’ in which Adam Roberts, Jerome Frank, Arne Naess and Gene Sharp discussed the possibilities of meeting invasion or coup d’état by nonviolent resistance. Adam Roberts in his introductory contribution states, ‘All the authors of the articles in this booklet consider that nonviolent action should be judged not in terms of a doctrine, which one may accept or reject, but as a technique, the potentialities of which in particular situations demand the most rigorous and careful study.’

It should be the task of science, even at the risk of shocking public opinion and making ‘creative misunderstandings’ more difficult, to reveal the doctrinal background of such a technique, i.e. to explain the ideas of the leaders of nonviolent resistance campaigns who, in deference to the outside world, pretended to be mere technicians of nonviolent action or who, at best, called themselves ‘practical idealists’ with the accent on ‘practical’.

Read the rest of this article »

by Nirmal Kumar Bose

Illustration art courtesy behance.net

Editor’s Preface: This article is the text of a speech delivered at the World Pacifist meeting in Shantiniketan, India, 1-5 December 1949, and continues our War Resisters’ International archive series. Nirmal Kumar Bose was an important figure in Gandhi’s life in the 1930s and 40s, and the author of an important diary of his life in Gandhi’s ashrams. For more biographical details please see the Editor’s Note at the end, along with an archive reference and a link to a pdf reproduction of the entire, original article. JG

India has tried to follow the principles of satya and ahimsa, truth and nonviolence, through centuries of her history. The actual application of these concepts has varied over the centuries and they have also been successfully employed in the solution of numerous problems relating to personal life or even group-life, where the group was based upon common religious experience.

Read the rest of this article »

by Purushottama Bilimoria

Indian actor Bagadehalli Basavaraju poses in classrooms as living statue of Gandhi; courtesy thebetterindia.com

Mohandas Karamchand [Mahatma] Gandhi adopted the metaphysics of a broadly-conceived Hindu religious thought for his social critique, out of which he developed a distinctive educational philosophy, which gave particular emphasis to truth and nonviolence, or the teaching of peace. In his social thinking he gave immense importance to what he called a ‘balanced’ form of education. By this he meant balanced as to needs, i.e. the necessities of life, against wants, i.e. whatever one yearns to possess, acquire or enjoy out of desire; and, more significantly, balanced as to internal values against a disproportionate concern with the externals (1948: 52). By ‘externals’ is meant the goods people generate and the sorts of activities, planning and manoeuvres people carry out in the normal course of living in order to meet the demands of commerce, material accessories, personal welfare and reproduction, and which are at the same time instrumental in sustaining the community.

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

Logo courtesy practicingparrhesia.tumblr.com

We noted in two previous essays comparing Gandhi and Foucault that our study was apparently the first specifically to compare the lives and philosophies of Mahatma Gandhi and Michel Foucault, and the first to suggest Gandhi as Foucault’s wished-for modern exemplar of the Hellenistic ideals of epimeleia heautou and parrhesia. Considering the mass of scholarship relating to the work of Foucault, and indeed the vast and meticulous output of the academic enterprise generally, it seems curious that we should be the first to draw these connections. This afterword will briefly inquire as to why this should be the case. Suggesting that possible concerns with our claims (Gandhi as exemplifying epimeleia and parrhesia) are generally unfounded, we will propose that this small lacuna rather reflects a greater and more troubling chasm between Eastern and Western philosophy in contemporary academia. We hope, therefore, that further projects may span the gap between two ancient traditions of human wisdom.

Read the rest of this article »

by Barbara Deming

Portrait of Deming c. 1960s, courtesy demingfund.org

Editor’s Preface: Barbara Deming (1917-1984) was a lesbian/feminist activist and proponent of nonviolent social change, her most notable work being Revolution and Equilibrium (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971). A foundation has been set up in her name to give financial support to women’s causes. Their website has further biographical information. This article is taken from War Resistance: Journal of the War Resisters, issue 39, fourth quarter, 1971. Please also see the archive reference information and acknowledgments at the end. JG

I have been asked to write about the relation between war resistance and resistance to injustice. There are many points to be made that I need hardly labor. I don’t have to argue at this date that if we resist war we must look to the causes of war, and try to end them. And that one finds the causes of war in any society that encourages not fellowship but domination of one person by another. We must resist whatever gives encouragement to the will to dominate.

I don’t think you would object to my stating the relationship between the two struggles in another way; restating it, for it has been often said: Bullets and bombs are not the only means by which people are killed. If a society denies to certain of its members food or medical attention, or a political voice, the sense of their own worth, the freedom to exercise their talents — this, too, is waging war of a kind.

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

Editor’s Preface: This essay is the second of three by Max Cooper comparing similarities between Gandhi and Michel Foucault. The first we posted 1 June and can be accessed via his Author’s Page, by clicking on his byline. Part Three will follow in a few days. Please also consult the Editor’s Note at the end for biographical information. JG

Cover art courtesy Semiotext(e)

We will here explore Foucault’s interests in the final years of his life in two particular ethico-spiritual practices native to ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophy: epimeliea heautou, the care of the self, and parrhesia, fearless truth-telling. Foucault saw such disciplines as important foundations for an ethical life; lamenting that such foundations could not be found in the modern age, he wished to draw attention to these practices in the hope that they might somehow be revived. We will argue here that Foucault need not have looked back over two thousand years to the ancient Greeks and Hellenes for examples of these practices, but could have found virtually identical practices in the life of Gandhi in his own century. We will suggest ultimately that Gandhi represented precisely the modern practitioner of epimeleia heautou and parrhesia that Foucault was looking for.

Examining certain classicist scholars’ criticisms of Foucault on his interpretation of these practices, we will entertain the striking possibility that Gandhi may have come closer to exemplifying these ancient practices and beliefs than Foucault did to explaining them. Next, we will examine Foucault’s intriguing distinction between ancient and modern philosophy as pertains to the care of the self: most ancient philosophers, Foucault suggested, viewed the attainment of knowledge as possible only after one had performed painstaking preparatory work on oneself; this often took the form of particular “spiritual practices.” Foucault felt that modern philosophy since Descartes had lost this emphasis on preparation for knowledge, to its own great detriment. We suggest that Gandhi, through his rigorous programme of self-purification performed with the goal of realizing Absolute Truth, embodies almost precisely the characteristics of epimeleia heautou that Foucault drew attention to in his classical sources: again, Foucault could have taken heart in Gandhi’s example.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Indian folk art representation of Gandhi’s assassination; courtesy Vinay Lal collection

Uniquely among the major public figures of the modern world, Mohandas Gandhi attracted an extraordinarily wide and diverse following and, perhaps oddly for someone who is customarily thought of in terms of veneration, an equally if not more diverse array of often relentlessly hostile critics. (1) The first part of this story is better known than the latter part of the narrative around which this paper is framed, (2) though much remains to be understood about the manner in which Gandhi, notwithstanding his rather strident views on modernity, industrial civilisation, materialism, sexual relations, indeed on everything that is ordinarily encompassed under the rubric of social and political life, drew to himself people from very different walks of life.

Among his most intimate disciples, who, it is no exaggeration to say, surrendered their life to the Mahatma, one thinks of the daughter of an English admiral, raised on the music of Beethoven in the lap of luxury and immense privilege; a Tamil Christian, trained as an accountant and economist, who was among the first Indians to earn a degree in business administration; a Gujarati villager, son of a schoolteacher, who was embraced by Gandhi when they first met in 1917 as something like a long-lost son; and an Anglican clergyman, arriving in India from Britain on what was destined to become a one-way ticket, who came to the realization that Gandhi was a better Christian than many who call themselves Christians. (3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

Poster art, courtesy indorigins.com

It may seem surprising that no significant study has as yet compared the lives, works, and ideas of Mahatma Gandhi and Michel Foucault. (1) Foucault (1926–1984), a French political and social theorist, and Gandhi (1869–1948), the saintly Indian political leader, initially appear to have very little in common, and indeed strike us as intellectual opposites. Gandhi was a deeply religious man who committed at least an hour each day to prayer and meditation; Foucault was a committed atheist who resented his bourgeois Catholic upbringing and blamed religion for much of the malaise afflicting modern man. Gandhi believed that human society and relationships could be transformed through individual hard work, selfless kindness, and love; Foucault was concerned to draw attention to hidden motivations of power in all social relations, and emphasized the often powerless positions of individuals vis-à-vis larger institutional structures. Gandhi fasted regularly, never took food after sunset, and upheld a vow of strict brahmacharya (celibacy) for the last 38 years of his marriage; Foucault maintained a fascination with intense sensory experiences, ever seeking stronger sensations through drugs and sex, and explored his interest in sexual pleasure in his final and definitive works, the three volume History of Sexuality. The reader could be forgiven for thinking that two more different men could hardly be found.

Read the rest of this article »