by Geoffrey Ashe

Dustwrapper art courtesy Stein & Day Publishing

Editor’s Preface: Gandhi was born in 1869 and as the centennial year of 1969 approached, pacifist and other publications worldwide used it as the occasion to re-evaluate Gandhi’s importance. The British cultural historian Geoffrey Ashe’s biography of Gandhi had been published to acclaim in early 1968 and Peace News published this article in their 16 August 1968 issue. It is the latest in our series of rediscoveries from the archives of the IISG in Amsterdam. Please see the notes at the end for references, acknowledgments, and further biographical information about Ashe. JG

Several months ago, Joan Baez described nonviolence as a flop, although she did qualify that by saying violence was a bigger flop. However, to my mind, we shouldn’t be downcast. By studying Gandhi’s nonviolence a little more carefully we can see what was right and wrong and make a fresh start. I am working on the Gandhi Centenary because I believe that some of the ideas which Gandhi explored in his career are still valuable and exciting, uniquely so; that these ideas can be restated and reapplied in the present context; but – what is perhaps the main thing – that no large-scale movement in this country has yet fully absorbed them or put them into practice.

Read the rest of this article »

by Rasoul Sorkhabi

Dustwrapper art courtesy Shambhala Publications; shambhala.com

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi in 1948 (sixty years ago as of this writing) and the renowned Trappist monk and author Thomas Merton was killed in a tragic accident in 1968 (forty years ago). These anniversaries are valuable opportunities to reflect on the legacies, works, and teachings of these two great men of peace. Gandhi has influenced many minds and movements of the twentieth century. In this article, we review Merton’s impressions of Gandhi and how they are helpful for our century and generation.

Thomas Merton, born in 1915, was 46 years younger than Gandhi. Merton spent the first two decades of his life in France, UK and USA. In 1939, he received his MA in English literature from Columbia University, and the following year accepted a teaching position at the Franciscan run Saint Bonaventure University in southwest New York State. In 1942 he decided to become a priest and entered the Abbey of Gethsemane, a Trappist monastery in Kentucky; the Trappist are strict observance Franciscans, and having taught at St. Bonaventure might have influenced his decision. Merton, or rather Father Louis as he was to be called at Gethsemane, lived the rest of his life there, a quiet and contemplative life in an inspiring natural environment. He kept journals and published innumerable essays, poems, and books. His autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, published in 1948 became a best seller. In the 1960s, Merton was attracted to Eastern religious thoughts and traditions, including Gandhi’s ideas.

Read the rest of this article »

by Tristan K. Husby

Dustwrapper art courtesy Polity Press; politybooks.com

The phrase “Those who can’t do, teach” is so well ingrained in the English vernacular that there is a range of variations, such as “Those who can’t teach, go into administration” or “Those who can’t teach, teach gym.” Knowledge of this phrase is so widespread that a current sit-com about incompetent teachers is simply titled “Those Who Can’t”. Less well known is that the Irish intellectual, playwright, and wit George Bernard Shaw coined this phrase. His original rendition, “He who can, does. He who can’t, teaches”, was one of the aphorisms in his Maxims for Revolutionists. Another axiom from the same book is “Activity is the only road to knowledge.”

That last sums up a great deal of the history of nonviolence. For to a great degree the history of nonviolence is a history of organizers, activists, and leaders first teaching others why nonviolence is an effective method and then working together with those people for change. The recent anthology, Understanding Nonviolence, edited by Maia Carter Hallward and Julie M. Norman (Malden, MA: Polity, 2015) aims to help aid in the discussion; it is explicitly pedagogical, with discussion questions and suggestions for further reading included in each chapter. Furthermore, jargon is kept to a minimum and the authors use endnotes sparingly. However, labeling this book as pedagogical does not mean that it is contains exercises for training nonviolent actions or flowcharts for planning strategies. Rather, this book is pedagogical in that it aims to help students study nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

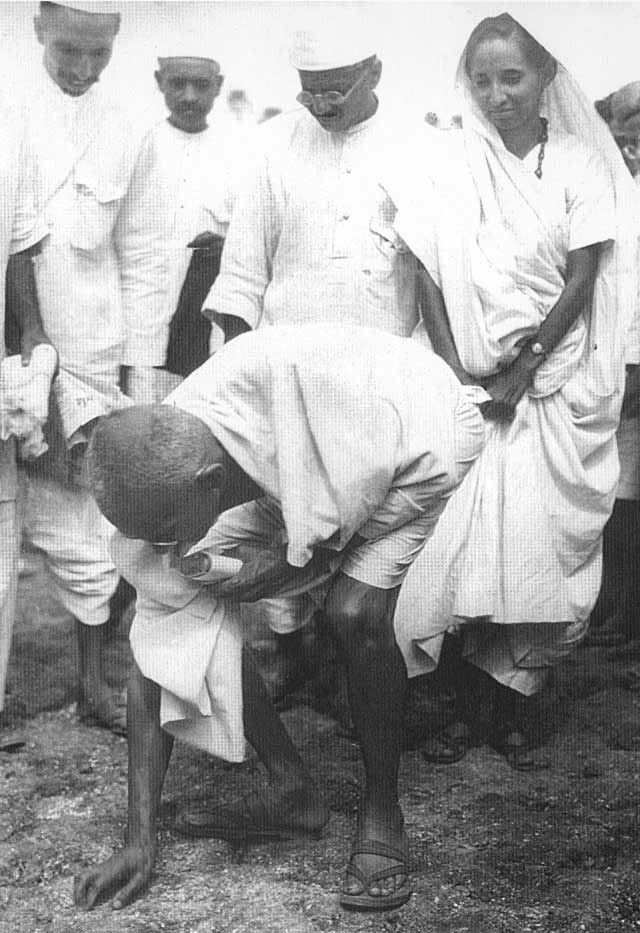

by William J. Jackson

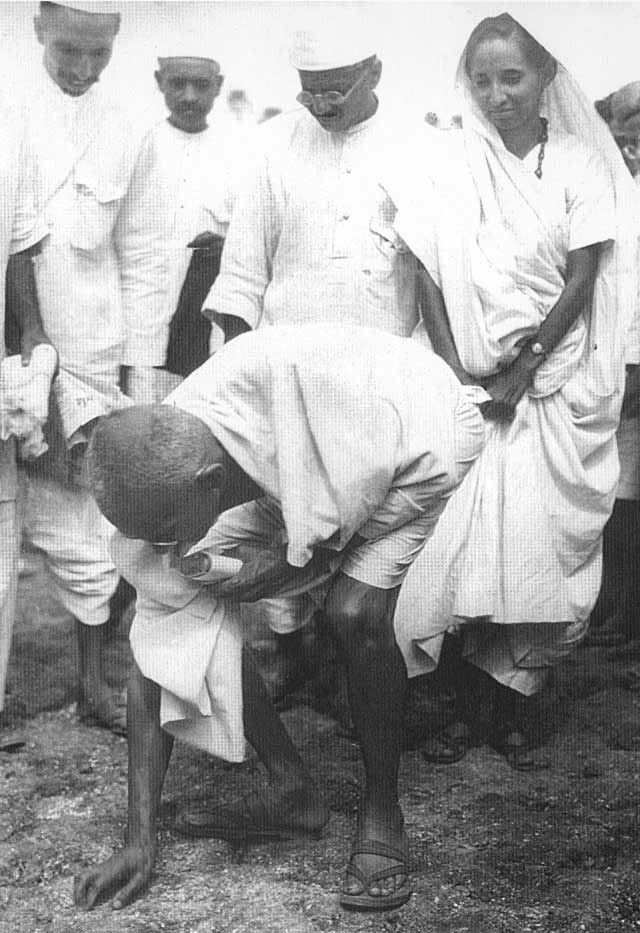

Gandhi gathers salt and breaks law; courtesy Wikipedia.com

Why Symbolism of Salt to Understand a Trouble Dissolver?

Alchemy is a kind of learning, a repository of old wisdom. It includes observations about elements, experiments with materials and aspects of the universe, as well as studies about processes and psyches. The imagination of curious souls and observers of life, active over the centuries, has experimented and found meanings in chemical and psychic interactions and transformations.

Despite modern science’s new technologies and ways of learning about the universe at various levels—micro, macro, meso—there are still valuable lessons to be learned from the ideas gathered under the term “alchemy” over the centuries. Shakespeare and other great poets are still interesting 500 years later—his grasp of human nature, his use of metaphorical language, and his observations on experience are still valuable, and this is true also for the metaphors found in alchemy.

James Hillman’s Alchemical Psychology is a brilliant contribution to understanding the richness of alchemy. In this book he garners and examines some valuable insights from the explorations of alchemy, and relates them to the processes of the human psyche. Many of the ideas in this paper are derived from Hillman’s inspiring work. I quote some points directly, others I paraphrase and elaborate on, extending them with my own examples and explicating and exploring their implications. Relating these ideas to Gandhi’s work is my idea, not Hillman’s. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Beverly Woodward

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished 1972 essay by Beverly Woodward is the latest in our series of discoveries from research that we are conducting in the IISG, Amsterdam. Please see the notes at the end for further details, references, acknowledgments, biographical information, and a link to the pdf file of the original. JG

The existing state of international disorder is often referred to as a state of global anarchy. The time honored human remedy for such a state of affairs is the establishment of the rule of law. Thus the remedy for the existing situation is often held to be the creation of more and better international law along with the creation of the institutions customarily associated with the presence of law, i.e., institutions for making, interpreting, and enforcing law. But there are many who are not enthused by the proposal. They include those national elites who speak piously of “law and order” at home, but are definitely less reverent when it becomes a question of forms of law that might be less supportive of their (self-defined) “interests” than the legal structures that they are so anxious to see upheld. They include the anarchists who insist that the current perversions in human behavior are not due to too little law, but to too much law, pointing out, for example, that it is governments that have authorized the great majority of the more brutal and massively destructive acts witnessed in this century. And they include many “ordinary people” who are neither opposed to law in general nor especially privileged by the given arrangements, but who are apprehensive of law formulated at such a great distance from its potential points of application. Even to those not inclined to rail against government wherever it occurs, “world government” or anything similar may seem a rather frightening remedy for what ails us.

Read the rest of this article »

by Tristan K. Husby

Dustwrapper art courtesy Brazos Press; bakerpublishinggroup.com

A friend of mine who is an organizer and nonviolence trainer has a favorite exercise called “10-10,” which she uses when introducing nonviolence to new activists. She divides the students into groups and tells them to write down, as quickly as possible, 10 wars. Afterwards, they review all of the different wars that people have recalled. While there are a number of wars that are repeated, often each group has come up with some war that other groups have not thought of at all. When I first participated in this exercise, I was excited to contribute the rather obscure Corinthian War. Then she asks the groups to write down 10 nonviolent struggles. This task always takes longer and some groups run out of time before they can complete the task.

The point of the “10-10” exercise is to drive home how our society pays close attention to wars and violent conflicts: We devote countless news articles, books and classes to retelling the history of these violent events. It is not surprising then that for the past 40 years much of the literature on nonviolence has been historical. Scholars and writers have uncovered, recorded and preserved examples of nonviolent struggles from across the world and from many different time periods so that activists can know for themselves and convince others of the efficacy of people power. Other writers, such as the philosopher Todd May and the theologian Ronald Sider, have adopted this idea of historical research being necessary to argue about and promote nonviolence in new books that they have each published.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Taoist compassion artwork; courtesy justgeneo.wordpress.com

The gently persuasive way—not beating others into submission, not bludgeoning, not eye-for-eye and tooth-for-tooth vengeance, but turning the other cheek, going the extra mile, giving more than is asked, killing the others’ “foeness” with kindness—is an ancient approach. It includes longsuffering, even self-sacrifice, loving your enemy, praying for those who persecute you. This is a Christian teaching, and is also ancient Taoist wisdom philosophy.

The Taoist classic text Tao Te Ching includes a number of lines about humility and not lording it over others, observations of patterns already recognized as very old wisdom 2500 years ago. TTC Chapter 68 is about the virtue of not contending; it speaks of “intelligent non-aggressiveness” and the “virtue of non-contention.” In Taoist philosophy one who accepts the “left tally, the debtor’s tally” (a symbol of inferiority in an agreement, getting the short end of the stick), humbly accepts the less prestigious position, which in the long run is the appearance the victor should have. To flaunt one’s victory sets a tone that brings resentment and reprisals. “Those who dispute are not skilled in Tao.” (TTC Chapter 81) Water flows downhill, and does not fight gravity. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Chaiwat Satha-Anand

Book jacket art courtesy usip.org

From 1982 to 1984, Muslims from two villages in Ta Chana district, Surat Thani, in southern Thailand had been killing one another in vengeance; seven people had died. Then on January 7, 1985, which happened to be a Maulid day (to celebrate Prophet Muhammad’s birthday), all parties came together and settled the bloody feud. Haji Fan, the father of the latest victim, stood up with the Holy Qur’an above his head and vowed to end the killings. With tears in his eyes and for the sake of peace in both communities, he publicly forgave the murderer who had assassinated his son. Once again, stories and sayings of the Prophet had been used to induce concerned parties to resolve violent conflict peacefully. (1) Examples such as this abound in Islam. Their existence opens up possibilities of confidently discussing the notion of nonviolence in Islam. They promise an exciting adventure into the unusual process of exploring the relationship between Islam and nonviolence.

This chapter is an attempt to suggest that Islam already possesses the whole catalogue of qualities necessary for the conduct of successful nonviolent actions. An incident that occurred in Pattani, Southern Thailand, in 1975 is used as an illustration. Finally, several theses are suggested as guidelines for both the theory and practice of Islam and the different varieties of nonviolence, including nonviolent struggle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

Anarcho-pacifist logo courtesy peaceofmindnews.com

The development of Christian Anarchism presaged the increasing convergence (but not complete merging) of pacifism and anarchism in the 20th century. The outcome is the school of thought and action (one of its tenets is developing thought through action) known as ‘pacifist anarchism’, ‘anarcho-pacifism’ and ‘nonviolent anarchism’. Experience of two world wars encouraged the convergence. But, undoubtedly, the most important single event to do so (although the response of both pacifists and anarchists to it was curiously delayed) was the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Ending as it did five years of ‘total war’, it symbolised dramatically the nature of the modern Moloch that man had erected in the shape of the state. In the campaign against nuclear weapons in the 1950s and early 1960s, more particularly in the radical wings of it, such as the Committee of 100 in Britain, pacifists and anarchists educated each other.

Read the rest of this article »

by Suzanne Duarte

Apollo image of earth; courtesy www.nasa.gov

Nature is stabilized by order, and humans along with all other natural phenomena exist within nature. Attempting to force one’s own path is arrogant, futile and self-destructive.

Lao Tzu

Everything depends on others for survival and nothing really exists apart from everything else. Therefore, there is no permanent self or entity independent of others. Not only are we interdependent, but we are an interrelated whole. As trees, rocks, clouds, insects, humans and animals, we are all equals and part of our universe.

Korean Zen Master Samu Sunim

Dharmagaians (1) are people who seek and speak the truth, cherish and protect the Earth, and act responsibly for the benefit of future generations of all sentient beings. They are not afraid to engage with the truth, the facts of our time, no matter how difficult and painful. In fact, many Dharmagaians have been doing so in writing and teaching for decades. Dharmagaians are also not afraid to allow themselves to feel the suffering of beings living now and those yet to be born, who will inherit a depleted planet.

One Dharmagaian ally, the cosmologist Brian Swimme, tells us that we are living in the most destructive moment in 65 million years. The Earth is withering under the onslaught of humans: our consumption of the biological and mineral endowment of the planet, and our pollution and waste. Species are going extinct at an unprecedented and increasing rate. Resources are declining and shortages are beginning to manifest in the parts of the world that are not already suffering them.

Read the rest of this article »