by Arvind Sharma

Gandhi poster courtesy rishikajain.com

Truth and nonviolence are generally considered to be the two key ingredients of Gandhian thought. It is possible to pursue one without the other, possible, for example, to pursue truth without being nonviolent. Nations go to war believing truth is on their side, or that they are on the side of truth. The more sensitive among those who believe truth is on their side insist not that there should be no war but that it should be a just war. The most sensitive, however, and pacifists are among these, avoid violence altogether. But it could be argued that in doing so they have gone too far and have abandoned truth, and even justice. Although he was opposed to war, Gandhi argued that the two parties engaging in it may not stand on the same plane: the cause of one side could be more just than the other, so that even a nonviolent person might wish to extend his or her moral support to one side rather than to the other.

Just as it is possible to pursue truth without being nonviolent, it is also possible to pursue nonviolence without pursuing truth. In fact, it could be proposed that a disjunction between the two runs the risk of cowardice being mistaken for, or masquerading as, nonviolence. The point becomes clear if we take the world “truth” to denote the “right” thing to do in a morally charged situation. Gandhi was fond of quoting the following statement from Confucius: “To know what is right and not to do it is cowardice.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Mohandas K. Gandhi

School of Andries Cornelis Lens, “Truth Protecting Us with Her Shield”, c. 1750; courtesy wikigallery.org

Editor’s Preface: “Truth”, “lies”, “alternate facts”, “post-truth politics”, etc., are terms very much in the air these days. Gandhi had much to say about Truth; the selection below is only a small sample focused on the root concepts behind his use of the term, and by application the root of his theory of nonviolence. This is the first of a series of articles we will be posting over the next few months on truth and truth in politics. Other statements on Satyagraha and Truth can be found on our Quotes and Sources page, via the link at the top of the page. JG

(I) The word Satya (Truth) is derived from Sat, which means ‘being’. Nothing is or exists in reality except Truth. That is why Sat or Truth is perhaps the most important name of God. In fact it is more correct to say that Truth is God, than to say that God is Truth. But as we cannot do without a ruler or a general, such names of God as ‘King of Kings’ or ‘The Almighty’ are and will remain generally current. On deeper thinking, however, it will be realised, that Truth (Sat or Satya) is the only correct and fully significant name for God.

And where there is Truth, there also is true knowledge. Where there is no Truth, there can be no true knowledge. That is why the word Chit or knowledge is associated with the name of God. And where there is true knowledge, there is always bliss (Ananda). There sorrow has no place. And even as Truth is eternal, so is the bliss derived from it. Hence we know God as Sat-Chit-Ananda, one who combines in Himself Truth, knowledge and bliss. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Glenn Smiley

Glenn Smiley riding on a bus with Martin Luther King, Jr., 1956; courtesy wagingnonviolence.org

Editor’s Preface: Rev. Glenn E. Smiley (1910-1993) had made a thorough study of Gandhian nonviolence (satyagraha) while serving as a Methodist minister in Los Angeles. He later worked for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and was national field secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). During World War II he went to prison for conscientious objection, but he is best remembered for his work with Martin Luther King, Jr. during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Please also see the note at the end for further information, acknowledgments, and links. JG

From the beginning of humankind’s time on the earth, for about 250,000 years, conflicts between individuals and groups have been settled on the basis of force, domination, or submission. In time, the use of force became more or less institutionalized, and continues to this day in many places.

Read the rest of this article »

by Richard B. Gregg

The Wheel of Integral Non-violence is courtesy of chico-peace.org

Editor’s Preface: This 1941 article, with its Foreword by Gandhi, continues our series of important historical documents on the theory and history of Gandhian nonviolence. Gregg here argues for the value of manual labor, as advocated by John Ruskin, and as practiced by Gandhi in his ashrams, where Gregg had lived. Gandhi considered spinning and weaving essential to the routine of a nonviolent community, yet this article is one of the very few to try to explicate this. Please also see the Editor’s Note at the end for more information about Gregg, and please also consult his other article, which we have posted here. JG

Foreword (by M. K. Gandhi): ‘A Discipline for Non-violence’ is a pamphlet written by Mr. Richard B. Gregg for the guidance of those Westerners who endeavour to follow the law of Satyagraha. I use the word advisedly instead of ‘pacifism’. For what passes under the name of pacifism is not the same as Satyagraha. Mr. Gregg is a most diligent and methodical worker. He had first-hand knowledge of Satyagraha, having lived in India and then too for nearly a year in the Sabarmati Ashram. His pamphlet is seasonable and cannot fail to help the Satyagrahis of India. For though the pamphlet is written in a manner attractive for the West, the substance is the same for both the Western and the Eastern Satyagrahi. A cheap edition of the pamphlet is therefore being printed locally for the benefit of Indian readers in the hope that many will make use of it and profit by it. A special responsibility rests upon the shoulders of Indian Satyagrahis, for Mr Gregg has based the pamphlet on his observation of the working of Satyagraha in India. However admirable this guide of Mr. Gregg’s may appear as a well-arranged code, it must fail in its purpose if the Indian experiment fails. (Sevagram, 24-8-1941)

A Discipline for Non-violence

For ages military discipline has won and held men’s faith. However crude, indiscriminate, and brief may be the results of organized violence, the world still has immense respect for its show of firmness and order. Much as we dislike war, when we begin to ask how we can attain justice and peace, we come face to face with this power of the military method. What is the secret of this power? Does it lie merely in men’s fear of violence?

Read the rest of this article »

by Tom Gibian

Sandy Spring School, 2nd Grade Art Work; courtesy grover.ssfs.org/~ksantori/art/2nd_grade.htm

One of the underlying principles of Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence is our capacity for interconnectedness, or as Gandhi was to state it, “the interconnectedness of all beings.” Interconnectedness, or connecting, is also very much at the heart of Quaker concerns.

I remember being in third grade and having to line up and pair off with a classmate to walk down the hallway to some destination beyond our classroom. At Sherwood elementary school, there might have been 29 or 30 nine-year-olds and one teacher. On the day I’m recalling, I was paired off with a kid named Sammy. I was new at Sherwood and someone warned me that Sammy had sweaty palms. As we headed down the hallway, he took my hand. His hand was sweaty, but it didn’t matter. We held hands without embarrassment. We were not self-conscious. We were little, at least relative to the world we were living in, and it could not have been more natural to reach out, to partner, to connect. Later, Sam would be one of the first friends of mine to get a high-performance muscle car in high school. That is a different story!

Read the rest of this article »

by Pope Francis

Giotto, “St. Francis Preaching to the Birds”; courtesy jssincivita.com.

Editor’s Preface: The following is the official Papal message for the 50th World Day of Peace, 1 January 2017. It is, however, the first such ever devoted exclusively to nonviolence, in the tradition of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. JG

1. At the beginning of this New Year, I offer heartfelt wishes of peace to the world’s peoples and nations, to heads of state and government, and to religious, civic and community leaders. I wish peace to every man, woman and child, and I pray that the image and likeness of God in each person will enable us to acknowledge one another as sacred gifts endowed with immense dignity. Especially in situations of conflict, let us respect this, our “deepest dignity”, (1) and make active nonviolence our way of life.

Read the rest of this article »

by Joseph Geraci

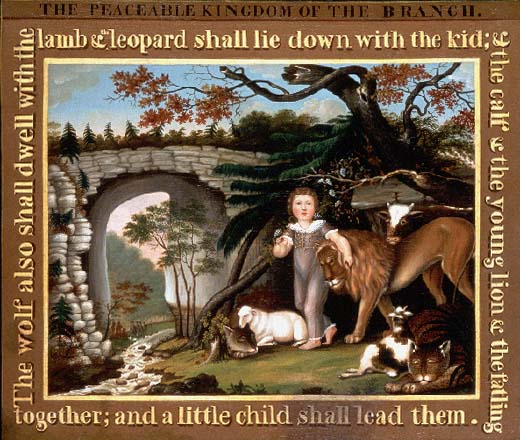

Edward Hicks painting, c. 1823, from the Peaceable Kingdom series; courtesy Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

Peace has been for centuries a universal greeting and sign. We may recall that the World War II military victory V-sign was transformed in the 1960s into a peace symbol; signs of the times. Peace was always more than a simple hello; it was a bestowal of peace on someone, a blessing. In the Middle East, for example, that area of the world so riven by violence, it is perhaps not so strange an irony that a common greeting is (in Hebrew) shalom aleikhem (Peace be with you), and the reply aleikhem shalom (Peace also be with you). In Arabic it is as-sal alaykum (Peace be with you), common to Muslims in Turkey, Indonesia, Central Asia, Iran, India, et al. The response is as-salamu alaykum, and can also be translated as “Peace also be with you”.

Read the rest of this article »

by SGI Quarterly

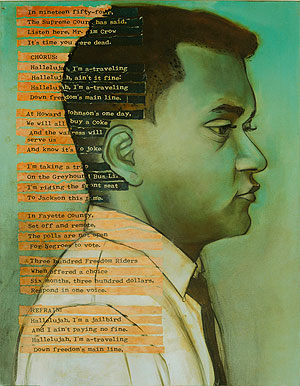

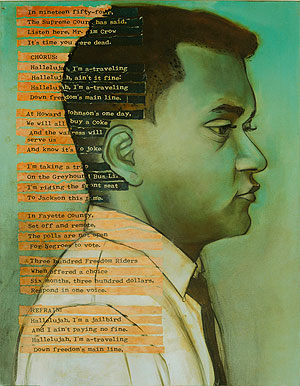

Painting by Charlotta Janssen based on mug shots of James Lawson after his arrest for a nonviolent protest in Jackson, Mississippi; courtesy charlottajanssen.com

Interviewer’s Preface: In the late 1950s, James Lawson moved to Tennessee as southern secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, where he began training students in Nashville in nonviolent direct action. Prior to that, he had spent a year in jail as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, and had also trained in nonviolence at various Gandhian ashrams in India. Described by Martin Luther King Jr. as “one of the foremost nonviolence theorists,” Rev. Lawson, now in his 80s, still remains a vibrant voice for social justice. SGI

SGI Quarterly: Do you remember a particular moment after you became involved in the Civil Rights Movement when you felt afraid?

James Lawson: I recall a number of moments of fear. But, I should say to you that those are isolated moments, and that from the beginning of my involvement character requirements froze out any fear. I was going to finish my graduate degree and then probably move south to work in the movement. I had spent three years in India, 1953-56, and then came back to Ohio for graduate school. I shook hands with Martin Luther King for the first time on February 6, 1957. By then I had been practicing and studying Gandhian nonviolence for ten years. And so as we met and talked, he said I should come south immediately. I said to him, “OK, I’ll come just as soon as I can,” which meant that I dropped out of graduate school and moved. There was no fear in making that move.

I don’t recall a single moment as I traveled around the South that I was frightened or fearful. And as we began the Civil Rights Movement in Nashville, I wasn’t aware of any moment of fear there either. I was expelled from the university and was made the target of many public attacks.

Read the rest of this article »

by Brett Keegan

Jacket art courtesy Rowman & Littlefield; rowman.com

Editor’s Preface: Barry Gan is professor of philosophy and director of The Center of Nonviolence, St. Bonaventure University, Saint Bonaventure, New York. The interview was conducted by his student, Brett Keegan, for the open source, academic website figureground.org and posted there October 28, 2013. For further information about Gan and acknowledgments please see the note at the end. JG

Brett Keegan: So, how did you get introduced to peace studies and nonviolent philosophy?

Barry Gan: The long story goes back to when I was a child. I was the only Jewish kid in a neighborhood of all Christians, and had been apprised by my parents that we were sort of different from everybody else in the neighborhood when we moved there when I was about six. And somehow, I always found myself in the role of peacekeeper among friends who were often getting involved with fights. I don’t know if it was out of fear, or just a sense of the stupidity of fights, but I never got involved. I would always try to talk people out of them, talk people through them.

Later, when I was at summer camp and my older brother was at summer camp with me, I remember there was this other kid there who was always getting picked on by everyone. And since I wasn’t from their school, I didn’t know why they were picking on him. I just found it annoying. And I remember challenging the bully at the time and wrestling him to the ground to get him to stop picking on this one kid.

Read the rest of this article »

by John Moolakkattu

Gandhi quote courtesy harshitkumargupta.wordpress.com

Scott Appleby, who has done extensive research on religion and politics, concludes that a new form of conflict transformation, namely religious peace building, is taking shape in and across local communities plagued by violence. (1) Since the end of the Cold War, there has been growing cooperation between nations and peoples in the Western hemisphere, and increasing number of apologies and acts of forgiveness throughout the world. This has prompted scholars of conflict resolution to shift their focus from conflict resolution to concepts such as reconciliation and forgiveness, concepts that reflect more correctly the spirit and practice of the new age. The power of forgiveness as a means of conflict resolution or transformation was emphasised by thinkers like Hannah Arendt, as it allows human beings to come to terms with their undesirable past, thereby changing the rule that governs the power relationship between the former victimiser and his or her victim. The application of ideas and beliefs that are relevant in the personal and religious realm to politics is however a project that many political realists would find difficult to accept.Forgiveness seems to represent the personal, the private and the spiritual. The sociologist and historian John Torpey writes that the influence of Holocaust consciousness is a factor contributing to the forgiveness discourse. (2) One can also see the direct influence of restorative justice practices such as criminal justice innovations and victim-offender mediation, often drawing on aboriginal justice. However, it is the encouraging results from the experience of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the revival of the Christian idea of forgiveness that also finds reflection in most religions in one form or the other, which made the concept popular in recent years. Some even see this as a sort of opportunity for national self-reflexivity and social healing. In other words, forgiveness, once dismissed as irrelevant in the field of conflict resolution during its technical phase of rational problem solving, has now become a theme of considerable import.

Read the rest of this article »