by War Resisters League

Dustwrapper art courtesy www.warresisters.org

Refusing to pay taxes for war is probably as old as the first taxes levied for warfare. We offer below a summary of such protest, which is to say it does not include other forms of tax refusal and resistance, a common tactic in worldwide labor movements, for example, or in various anti-colonial protests including such well-known examples as the Boston Tea Party.

Indeed, until World War II, war tax resistance in the U.S. manifested itself primarily among members of the historic peace churches — Quakers, Mennonites, and Brethren — and usually only during times of war. There have been instances of people refusing to pay taxes for war in virtually every American war, but it was not until World War II and the establishment of a permanent, centralized U.S. military (symbolized by the building of the Pentagon) that the modern war tax resistance movement was born.

Colonial America

One of the earliest known instances of war tax refusal took place in 1637 when the relatively peaceable Algonquin Indians opposed taxation by the Dutch to help improve their local Fort Amsterdam. Shortly after the Quakers arrived in America (1656) there were a number of individual instances of war tax resistance. For example, in 1709 the Quaker Assembly refused a request of £4000 for a military expedition into Canada, replying, “It is contrary to our religious principles to hire men to kill one another.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Lawrence Rosenwald

Poster art of Thoreau courtesy pinterest.com

Doing tax resistance has for me been connected with thinking about Thoreau, whose works I often teach in my classes. I used not to teach “Civil Disobedience,” but only Walden; although I admired “Civil Disobedience” very much, but couldn’t bring myself to teach it. It is an essay intended as an argument; I knew that if I taught it I would present it as an argument, as an argument I found reasonable and compelling, and then, I thought, some alert and nervy student would ask, “If you think it’s such a good argument then why are you paying your taxes?” And then I’d either mutter something about how times have changed, or say I was a coward, and I knew I wouldn’t like myself in either case. But when my wife and I began doing tax resistance, I began to teach “Civil Disobedience,” and in fact teaching it — not proselytizing with it, but teaching it on a footing of equality — is among the rewards doing tax resistance has brought me.

So I want to talk about Thoreau, first, and about the ideas his tax resistance came from; and then about myself, as someone who finds Thoreau’s stance attractive but who knows that, after all, times have changed, and that doing tax resistance now is different from doing it then, and grimmer; and generally about why so many people with political views similar to mine don’t find Thoreau attractive or at any rate don’t do tax resistance, and how this can perhaps be changed.

Read the rest of this article »

by National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee

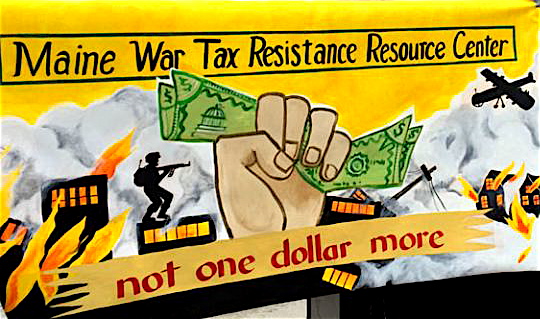

Poster art courtesy nwtrcc.org

Editor’s Preface: This article continues our series of statements of purpose by various nonviolence organizations. The National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee (NWTRCC) is a coalition of U.S. local, regional, and national groups and individuals supporting, as they state, “individuals who refuse to pay for war, and promoting U. S. war tax resistance in the context of a broad range of nonviolent strategies for social change.” Their website is a primary source of information on war tax resistance, including tactics and legal consequences. Please see the note at the end for acknowledgments, further information, and links. JG

What is War Tax Resistance?

War tax resistance means refusing to pay some or all of the federal taxes that pay for war. While you can refuse income tax legally by lowering your taxable income, for many people war tax resistance involves civil disobedience. In the U.S. war tax resisters refuse to pay some or all of their federal income tax and/or other taxes, such as the federal excise tax on local telephone service. Income taxes and excise taxes are destined for the government’s general fund and about half of that money goes for military spending, including weapons of war and weapons of mass destruction. Through the redirection of our tax dollars, war tax resisters contribute directly to the struggle for peace and justice.

Read the rest of this article »

by David Gross

Dustwrapper art courtesy David Gross; sniggle.net/TPL/index5.php

Editor’s Preface: This article was written in March 2003 as a response to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. David Gross went on to become a leading figure in the tax resistance movement. Please see his compilation of John Woolman’s writings, previously posted here, and see also the note at the end for further information, acknowledgments, and links. JG

When the war in Iraq started, [March 20, 2003] and especially when it escalated into a full-blown invasion, I gave notice at work. My intention was to reduce my income below the threshold of taxation so as to stop paying income tax to the U.S. government. I’m writing this to explain myself to my friends, who will notice a bit of a change of lifestyle in me in the coming months. Also, I write because writing calms my nerves, and I’m a bit nervous about this. I’m starting on an experiment, and I’m not sure where it will take me.

I take on faith the philosophical speculation that each of us has free will. It does seem that a lot of the evidence lately has been going in the other direction, but that doesn’t stop me. If I’m right, I have the opportunity to try my hand at the controls. If I’m wrong, I couldn’t change my mind if I wanted to, no?

Read the rest of this article »

by David Hartsough, Kit Miller, Michael Nagler, Miki Kashtan, Ruth Benn

Poster art courtesy National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee; nwtrcc.org

Editor’s Preface: The letter reproduced below is a joint appeal from leading nonviolent activists and organizations, urging US taxpayers to nonviolently express their opposition to the policies of the Trump administration by refusing to pay a symbolic amount of their US federal income tax, and instead donate that amount to a deserving charity or institution. This method of nonviolent civil resistance has many historical precedents in the U.S., most notably the Quaker John Woolman’s 18th century statements, which we previously posted. JG

Dear Friends,

We are writing to ask you to do something that you probably have never done in your life. This is a historical moment you can be an active part of shaping.

We all know the stories of people who committed atrocities and said, in their defense, that they were following orders.

Read the rest of this article »

by David Gross

Dustwrapper art courtesy David Gross; sniggle.net/TPL/index5.php

Editor’s Preface: Tax resistance is one of the oldest nonviolent tactics, some citing a Jewish Zealot Revolt of c. 60-70 CE as the first. We are inaugurating our new series on the subject with this article about the 18th century Quaker, John Woolman. His call to conscience was one of the more influential texts on early American civil disobedience and resistance. If anything tax resistance is now not only more relevant, but more prevalent. We are posting two versions of John Woolman’s tax resistance writings; the first reproduces the original journal entries, and retains, therefore, Woolman’s spelling and grammar, with exceptions in square brackets. The second, Harvard Classics version, modernizes the language. JG

The American Quaker John Woolman (1720-1772) was a pioneer of conscientious tax resistance, and he has left a record of how he wrestled with his conscience over whether or not to pay taxes for the French and Indian War. (1) As he wrote, “To refuse the active payment of a Tax which our Society generally paid, was exceedingly disagreeable; but to do a thing contrary to my Conscience appeared yet more dreadfull . . . I knew of none under the like difficulty, and in my distress I besought the Lord to enable me to give up all, that so I might follow him wheresoever he was pleased to lead me.” (2)

Read the rest of this article »