by Eileen Egan

Photo collage with CW masthead; artist unknown; courtesy of the CW

Nonviolence has a negative, passive ring to it that its adherents have been attempting to erase by prefixing to it the adjective “militant.” Regrettably, it is the only current term in general usage in English. It corresponds to the Gandhian ahimsa, or non-injury, and carries the necessary message of unwillingness to injure or kill other creatures. For Western adherents of ahimsa or nonviolence who are not vegetarians, the unwillingness applies only to humans. The nonviolent person is not supine before an insane attack. The defense of a third party often involves the interposing of the body of the nonviolent person, with no intent of inflicting harm. Gandhi coined the term satyagraha, or truth-force, to describe a nonviolent campaign for human rights and freedom. As “God is Truth and Truth is God” in Gandhi’s thinking, the inference was that only godly or moral force would be employed by satyagrahi, participants in the nonviolent movement. Martin Luther King’s term, “soul-force” is a satisfactory one for most adherents of nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Dorothy Day

Editor’s Preface: Dorothy, of course, wrote innumerable anti-war articles for The Catholic Worker. So why choose this one to accompany the Gandhi Center in Berlin’s “Manifesto against Conscription and the Military System”, also posted today? Of all of Dorothy’s pacifist articles, reportage, statements of principle, this article is filled with a certain righteous anger that she did not often allow to seethe through her other CW writings, a righteous indignation that intensifies the moral purpose and message. JG

Is it Soviet Russia who is the threat to the world? Is it indeed? Then may we quote from Scott Nearing’s The Way of the Transgressor? (1) “What nation today has a navy bigger than all other navies combined? The USA. What nation today is steadily adding to the only known stockpile of atom bombs? The USA. What nation today is tops in the development of buzz bombs, jet planes, bacterial poisons and death rays? The USA. What nation today is spending the largest sums on military preparations? The USA. What nation today is permitting representatives of the armed forces to take over the direction of domestic and foreign policy? The USA. What nation today is arming its neighbors (in Latin America), intervening in the internal affairs of Europe and Asia, threatening the world peace and security and rapidly surrounding itself with a black curtain of anxiety, suspicion and hatred? The USA.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

Thomas Merton; photograph by John Howard Griffin.

This is the text of the annual Oakham lecture, given in April 2012 at the meeting of the Thomas Merton Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Oakham School, England.

What initially put Merton on the world map was the publication in 1948 of his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. It was an account of growing up on both sides of the Atlantic (part of his adolescence was spent here at Oakham), what drew him to become a Catholic as a young adult, and finally what led him, in 1941, to become a Trappist monk at a monastery in rural Kentucky, Our Lady of Gethsemani. He was only 33 years old when the book appeared. To his publisher’s amazement, it became an instant bestseller. For many people, it was truly a life-changing book. I have lost count of how many copies of the book have been printed in English and other languages in the past 64 years, but we’re talking about millions.

Merton was and remains a controversial figure. Though he was a member of a monastic order well known for silence and for its distance from worldly affairs, Merton was outspoken on various topics that many regard as very worldly affairs. Merton disagreed. He was a critic of a Christianity in which religious identity is submerged in national or racial identity and life tidily divided between religious and ordinary existence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

Dorothy Day in her room at the CW Farm. Tivoli, New York; c. 1970; photo by Bob Fitch

I first met Dorothy Day a few days before Christmas in 1960 while on leave from the U.S. Navy. After reading copies of The Catholic Worker that I had found in my parish library, and then reading Dorothy’s autobiography, The Long Loneliness, I decided to visit the community she had founded. I was based not so far away, in Washington, DC.

Arriving in Manhattan for that first visit, I made my way to Saint Joseph’s House — then in a loft on Spring Street, on the north edge of Little Italy in the Lower East Side of New York City. Discovering that it was moving day, I joined in helping carry boxes from an upstairs loft to a three-storey brick building at 175 Chrystie Street, a few blocks to the east. Jack Baker, one of the other people assisting with the move that day, invited me to stay in his apartment in the same neighborhood. A few days later I visited the community’s rural outpost on Staten Island, the Peter Maurin Farm. Crossing Upper New York Harbor by ferry, I made my way to an old farmhouse on a rural road just north of Pleasant Plains near the island’s southern tip. In its large, faded dining room, I found half-a-dozen people, Dorothy among them, gathered around a pot of tea at one end of the dining room table.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest & Nancy Forest

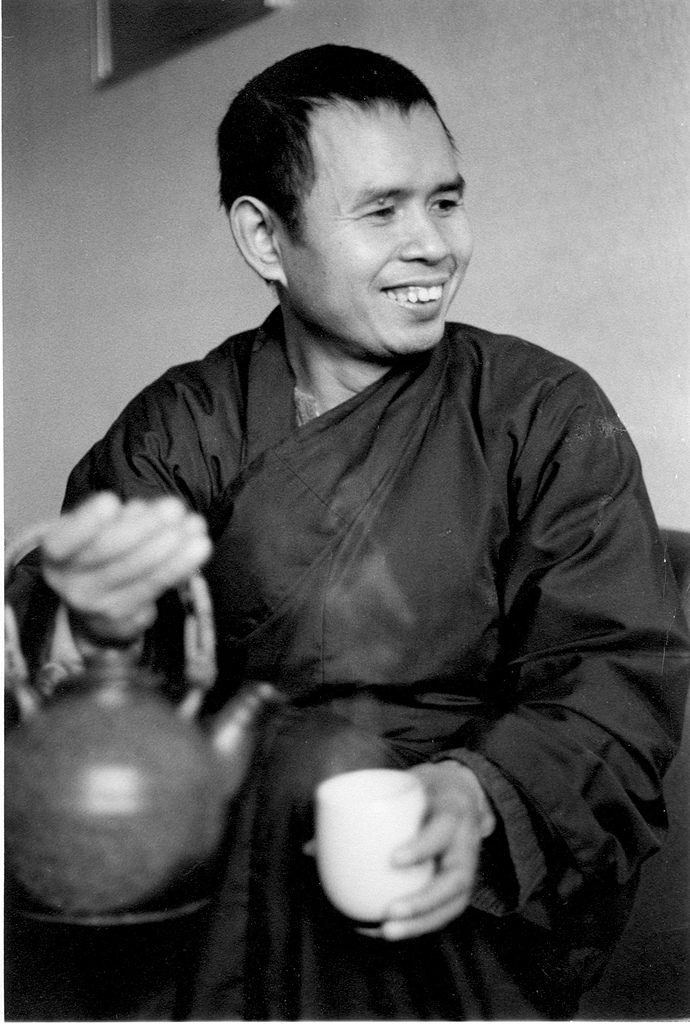

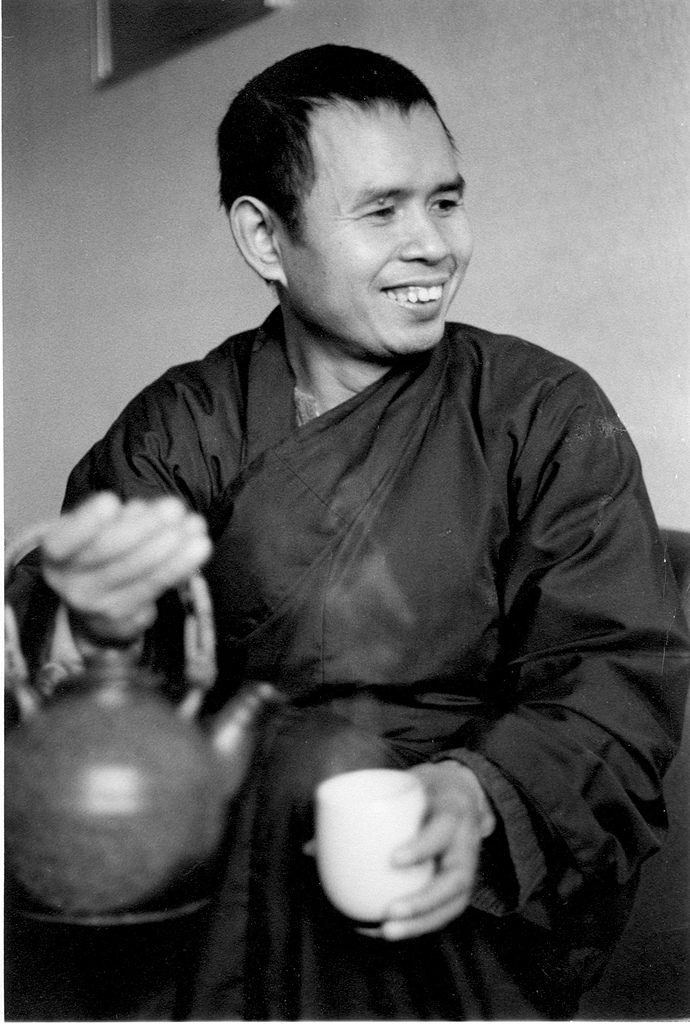

Original gelatin silver print photo by Jim Forest c. 1970.

I traveled and also at times lived with Thich Nhat Hanh in the late sixties through the seventies. Here are extracts from various letters in which Nancy and I relate a few stories about him. In these passages Nhat Hanh is sometimes called “Thay”, the Vietnamese word for teacher.

I sometimes think of an evening with Vietnamese friends in a cramped apartment in the outskirts of Paris in the early 1970s. At the heart of the community was the poet and Zen master, Thich Nhat Hanh. An interesting discussion was going on in the living room, but I had been given the task that evening of doing the washing up. The pots, pans and dishes seemed to reach half way to the ceiling on the counter of the sink in that closet-sized kitchen. I felt really annoyed. I was stuck with an infinity of dirty dishes while a great conversation was happening just out of earshot in the living room.

Somehow Nhat Hanh picked up on my irritation. Suddenly he was standing next to me. “Jim,” he asked, “what is the best way to wash the dishes?” I knew I was suddenly facing one of those very tricky Zen questions. I tried to think what would be a good Zen answer, but all I could come up with was, “You should wash the dishes to get them clean.” “No,” said Nhat Hanh. “You should wash the dishes to wash the dishes.” I’ve been mulling over that answer ever since — more than three decades of mulling.

Read the rest of this article »

by John David Muyskens

A commercial on TV shows a fierce looking man who says, “Why we fight is like asking why leaves fall. It is just our nature.” And that seems to be the nature of many people. But we can gain another nature.

We seem to be wired to try violence as a way to deal with violence. But violence only leads to more violence. If we can learn the art of love we will be able to get along so much better. We have a tendency to rush to judgment about people. We so quickly think ourselves better than others. But in reality we are all in the boat of life together.

One way to gain a loving nature is a form of contemplative prayer, called “Centering Prayer,” engaging us in silent, communion with God. In contemplation, we enter a presence rather than asking for anything. We accept the way things are. Centering Prayer changes us because for the moment we lose control. We are quiet. We let God give us whatever God wants to give. Not what we expect but what God gives. We give our consent to God’s presence and action in us. It is not a matter of doing but of being.

Read the rest of this article »

by Thomas Merton

It would be a serious mistake to regard Christian nonviolence simply as a novel tactic which is at once efficacious and even edifying, and which enables the sensitive person to participate in the struggles of the world without being dirtied with blood. Nonviolence is not simply a way of proving one’s point and getting what one wants without being involved in behavior that one considers ugly and evil. Nor is it, for that matter, a means which anyone legitimately can make use of according to his fancy for any purpose whatever. To practice nonviolence for a purely selfish or arbitrary end would in fact discredit and distort the truth of nonviolent resistance.

Read the rest of this article »

by John Dear

Like all of you, Thomas Merton has been one of my teachers, and it’s a blessing to reflect on his exemplary life and astonishing witness.

I’m 45, have been in the Jesuits almost 25 years now, went to college at Duke University, decided one day that I really did believe in God and that I wanted to give my whole life to God, and the next thing you know, I was entering the Jesuits. I’m still trying to figure out how that happened! Before I entered the Jesuits, I decided I better go see where Jesus lived, so I decided to make a walking pilgrimage through Israel, to see the physical lay of the land, only the day I left for Israel in June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon and I found myself walking through a war zone.

Read the rest of this article »

by Shinichi Yamamuro

“Philosopher’s Garden: Kyoto, Japan, 2012”; original photograph, by Michael Sawyer.

Non-violence often comes to mind when we think of the term ahimsa, which, for example, Gandhi used. The word himsa in Hindi means, “to inflict injury on a person,” in other words to hurt a person. The word ahimsa, “non-violence,” is formed by adding the negative adverb a. What exactly is “inflicting injury”? Naturally, it is easy to understand physical violence, such as war, in which people are harmed, but are there other ways of inflicting injury? If so, how should we understand non-violence?

Read the rest of this article »

by Dr. L. M. Singhvi

The Jain tradition, which enthroned the philosophy of ecological harmony and non-violence as its lodestar, flourished for centuries side by side with other schools of thought in ancient India. It formed a vital part of the mainstream of ancient Indian life, contributing greatly to its philosophical, artistic and political heritage. During certain periods of Indian history, many ruling elites as well as large sections of the population were Jains, followers of the Jinas (Spiritual Victors).

The ecological philosophy of Jainism, which flows from its spiritual quest, has always been central to its ethics, aesthetics, art, literature, economics and politics. It is represented in all its glory by the 24 Jinas or Tirthankaras (Pathfinders) of this era whose example and teachings have been its living legacy through the millennia.

Although the ten million Jains estimated to live in modern India constitute a tiny fraction of its population, the message and motifs of the Jain perspective, its reverence for life in all forms, its commitment to the progress of human civilization and to the preservation of the natural environment continues to have a profound and pervasive influence on Indian life and outlook.

In the twentieth century, the most vibrant and illustrious example of Jain influence was that of Mahatma Gandhi, acclaimed as the Father of the Nation. Gandhi’s friend, Shrimad Rajchandra, was a Jain. The two great men corresponded, until Rajchandra’s death, on issues of faith and ethics. The central Jain teaching of ahimsa (non-violence) was the guiding principle of Gandhi’s civil disobedience in the cause of freedom and social equality. His ecological philosophy found apt expression in his observation that the greatest work of humanity could not match the smallest wonder of nature.

Read the rest of this article »