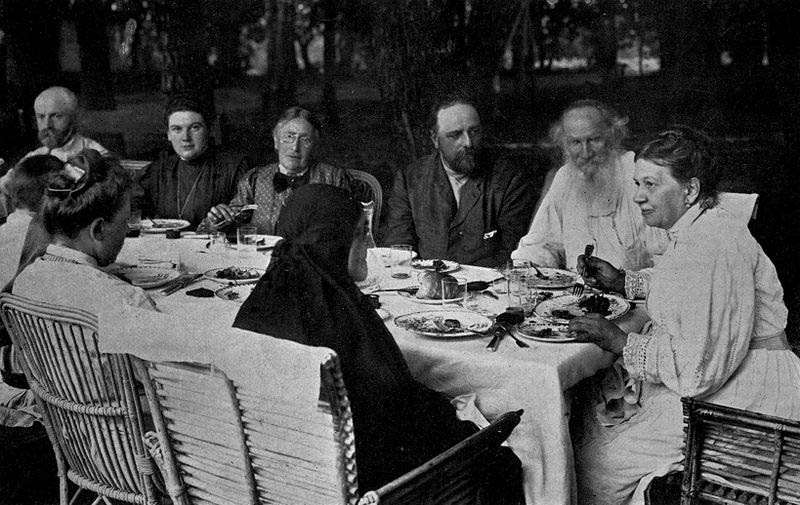

Tolstoy family gathering, 1905; Tchertkov to Tolstoy’s right; photographer unknown.

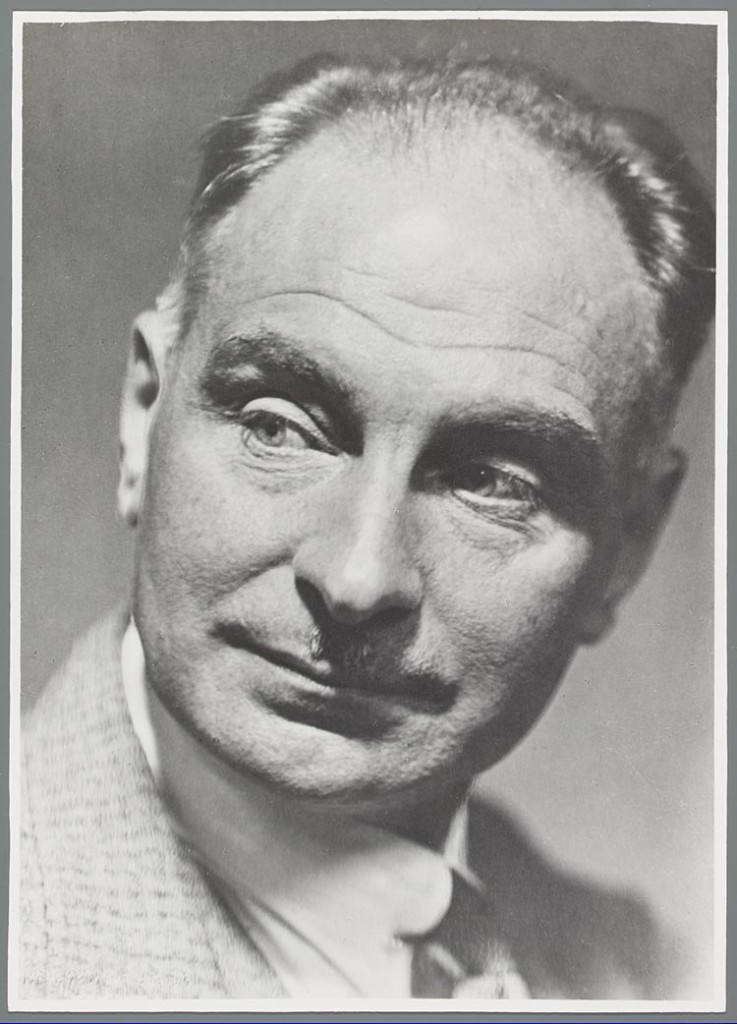

My article, “My Attitude Towards War”, published in Young India, 13th September 1928, has given rise to much correspondence with me and in the European press that is interested in war against war. In the personal correspondence there is a letter from Tolstoy’s friend and follower, V. Tchertkov, which, coming as it does from one who commands great respect among lovers of peace, the reader will like me to share with him. Here is the letter:

Personal Letter from Vladimir Tchertkov

Your Russian friends send you their warmest greetings and best wishes for the further success of your devoted service for God and men. With the liveliest interest do we follow your life, the work of your mind, and your activity, and we rejoice at each of your successes. We realize that all that you attain in your own country is at the same time also our attainment, for, although under different circumstances, we are serving the one and the same cause. We feel a great gratitude to you for all that you have given and are giving us by your person, the example of your life, and your fruitful social work. We feel the deepest and most joyous spiritual union with you.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bart de Ligt

From Germany, Austria and other countries, I have been urged for information about my correspondence with Gandhi, which so far has only been published in French, English and Dutch and for various reasons could not be published in German. I am therefore most grateful to the editorial staff of Neue Generation (New Generation) for the opportunity to acquaint you with a few matters.

It was only in 1928 that I could really go more profoundly into Gandhi’s life. I had read, of course, with great interest a number of his articles. As well as that, I had taken note of various articles written about him. The most important insights I owe to the short book by Romain Rolland (Mahatma Gandhi, 1922) and a few articles published in magazines.

From these I came to understand Gandhi as the legitimate follower of Tolstoy. Whereas Tolstoy would have been the “John the Baptist” of revolutionary nonviolence, Gandhi would have been the Christ, so to speak, of this movement; Tolstoy the Great Precursor and Prophet, Gandhi the Performer fulfilling the Prophecy.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bart de Ligt

At the Congress of War Resisters, held in Lyons, August 1931, Tolstoy’s last secretary, Valentin Bulgakov spoke of the “great experience” gained by India in its struggle against England. Not without reason did he express admiration for the role Gandhi played in this struggle. But Bulgakov tended to attribute to the Mahatma an attitude that was consistently hostile to any sort of violence, an attitude which, according to Gandhi himself, does not correspond with the facts.

In Le Semeur of October 15th, 1931, Bulgakov also declared that the correspondence which Vladimir Tchertkov and I have had with the Indian leader, regarding Gandhi’s attitude during the Boer War, the Zulu-Natal War and the World War, concerns only “a few ill-advised declarations” of Gandhi, “purely accidental” and remaining “without effect; Gandhi’s actions demonstrating that he in no way approves of cooperation with violence.”

Read the rest of this article »

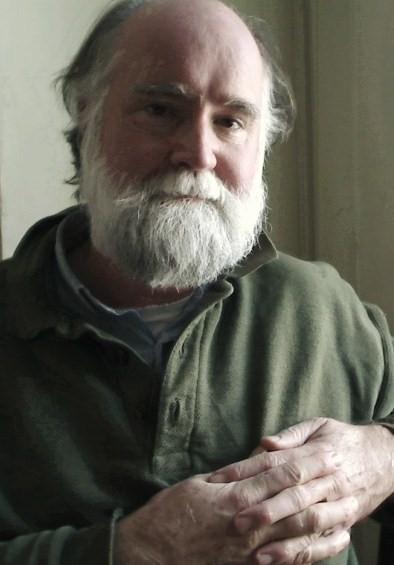

by Richard Gregg

Those who are familiar with Gandhi’s life will recall that up to 1919 he believed that the British Empire did more good than harm to the world and to India. He had not then evolved his program of hand spinning and weaving, nor in his South African struggles had he used the boycott or refusal to pay taxes as political weapons. He has stated that up to that time he did not have strength to resist war effectively.

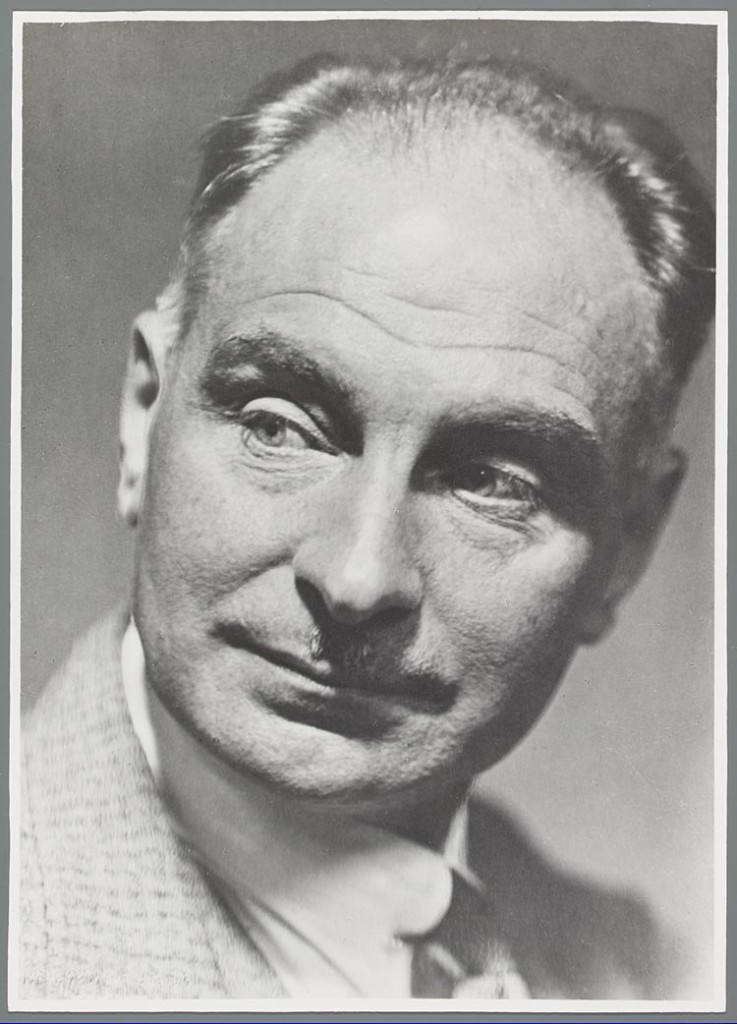

Richard Gregg, c. 1930s, photographer unknown; courtesy Quakers in the World.

Therefore, I think that he did war service because up till then he did not realize the extent of violence and untruth inherent in the State; he did not fully understand the complex and subtle nature of its control over people; and had not yet devised practical methods of ending that control. Nevertheless, he knew that war is only a result, a final stage of a psychological process that begins with fear, anger and greed. In organized social life most of us support the State by paying taxes, by buying articles from people or corporations that similarly support the State, and by not effectively helping others to escape this domination. To refuse military service after taking part in all this is merely to lock the stable door after the horse is stolen. Gandhi seems to have preferred to take some part in war to see if somehow he could render good for evil. Innocent or inconsistent perhaps, but with deeper understanding than that of most.

Read the rest of this article »

by Peter van den Dungen

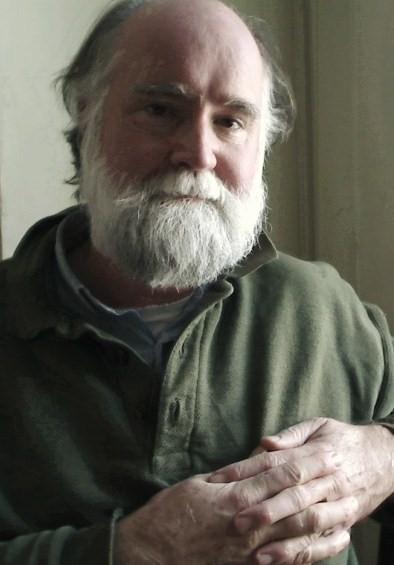

Bart de Ligt c. 1935; Public domain image; photographer unknown; courtesy of International Institute for Social History.

On 3 September 1938, within a year of the publication of The Conquest of Violence (his only book translated into English), Bart de Ligt collapsed and died in the railway station at Nantes. He had been taken ill in Bretagne and was on his way home to Geneva. Only 55, he had led such an intensively active public life, fully dedicated to the struggle for a better society, that this time his exhaustion proved to be fatal. His wife, who was his close collaborator, said that his life was like a flame, which had been extinguished too soon. But it had been a brilliant flame which had illuminated the thoughts, warmed the feelings, and lit or fanned the fervour of all those who had the good fortune to come into contact with him either directly through his countless public lectures, speeches and organisational activities, or indirectly through his equally numerous publications. It may be regarded as symbolic that he died in Nantes, the city where Henry IV signed the Edict granting freedom of conscience and worship to the French Protestants (who had been killed in their thousands in the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572 and afterwards), for de Ligt was a fighter of all dogma, whether religious or secular, and a fearless defender of all those who, in the past as in his own day, were branded heretics. Being a chief among them, he conducted his own kind of inquisition which was one relentless exposition of, and opposition to attitudes, practices and institutions which resulted in the enslavement of the individual and the establishment of a society which was far from truly human.

Who was this iconoclast who likeminded contemporaries regarded as a ‘superior spirit’ and an ‘exceptional figure’ in Dutch intellectual life? The relatively few people, then as now, in Holland and abroad, who know and admire de Ligt’s social philosophy and social action – against war and all the things which make for war – saw him as a figure bearing comparison with Erasmus, whom he resembled in several ways, and whose biography, published in Dutch in 1936, was his last book.

Read the rest of this article »

by Nathan Schneider

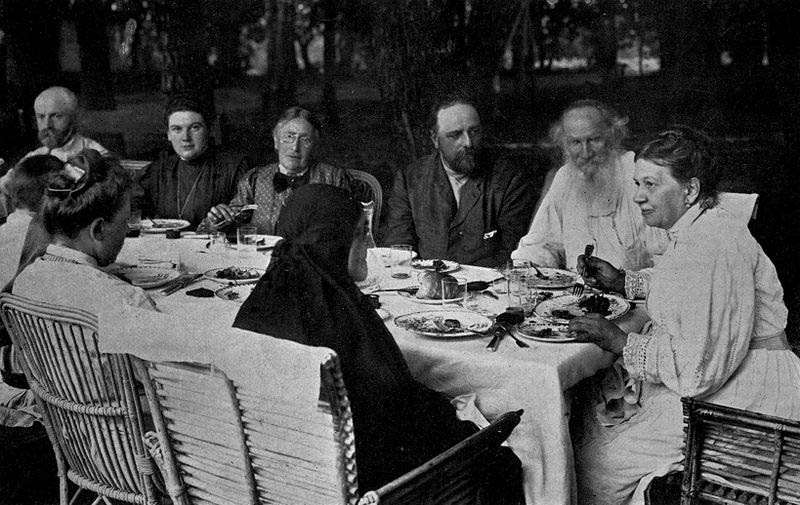

Nicholson Baker; public domain photograph; courtesy of Wikipedia.com

Anyone who makes even a modest habit of speaking out against war in public soon runs up against the inevitable, supposedly unanswerable question: What about World War II? It’s meant to be the ultimate stumper. This was the “good war,” wasn’t it, the war waged by the “greatest generation” against the evil incarnate of Hitler and imperial Japan? There was simply no other choice before the forces of goodness and truth but to leap into the single most deadly undertaking in all of human history. Right?

That won’t work if you’re talking to Nicholson Baker. In an extraordinary cover story in Harper’s Magazine, “Why I’m a Pacifist: The Dangerous Myth of the Good War,” Baker explains how learning about World War II was actually a big part of what made him a pacifist in the first place. “In fact,” he writes, “the more I learn about the war, the more I understand that the pacifists were the only ones, during a time of catastrophic violence, who repeatedly put forward proposals that had any chance of saving a threatened people. They weren’t naïve, they weren’t unrealistic—they were psychologically acute realists.”

Read the rest of this article »