The Daily Work before Sunrise: A Fairy Tale

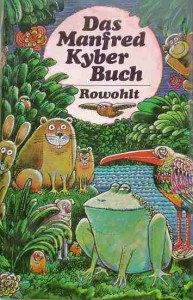

Cover art for Kyber’s fairy tales; courtesy buchladen-joerg.de

Once upon a time, there was a blacksmith’s workshop and a blacksmith who labored there each day.

This blacksmith was unique, because his daily work was finished before sunrise.

It is a very difficult kind of daily work, which this blacksmith does. A person doing this kind of work becomes weary and sad. And one becomes calm and patient because of it, too. This kind of labor takes a lot of strength. Because someone who does this kind of work lives alone, and hammers in the twilight.

Now it was night, and the blacksmith was not at his forge. The fire-spirit in the chimney slept too. Only the fire-spirit’s breath faintly glowed off and on, glimmering under the ashes, and now and then scattering sparks around in the darkness. But the sparkles soon went out. Only a small gleam of light remained, and when it flickered, it cast glowing light beams that seemed to hurry here and there on the floor and walls, as if wandering and seeking something in the darkness of the smithy.

The relaxed bellows let its great stomach hang in plain glum folds, though when it is folded it becomes slimmer. It reminds us of how a stout master can grow skinny all of a sudden. One could have laughed about this, but in the smithy there was no one who understood how to laugh.

The anvil turned his fat head with its sharp pointed nose slowly in each direction, and looked at the old pieces of iron which would be hammered today. It was not much to look at. Only a few worn pieces huddled together. They lay in a corner, and they were dirty and dusty, like folks who have a long and difficult journey behind them.