by John Dear

Daniel Berrigan marches for peace and against nuclear arms; New York City, 1982; photo courtesy AP

Rev. Daniel Berrigan, the renowned anti-war activist, award-winning poet, author and Jesuit priest, who inspired religious opposition to the Vietnam War and later the U.S. nuclear weapons industry, died on 30 April at age 94, just a week shy of his 95th birthday. He died of natural causes at the Jesuit infirmary at Murray-Weigel Hall in the Bronx. I had visited him just last week. He has long been in declining health.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

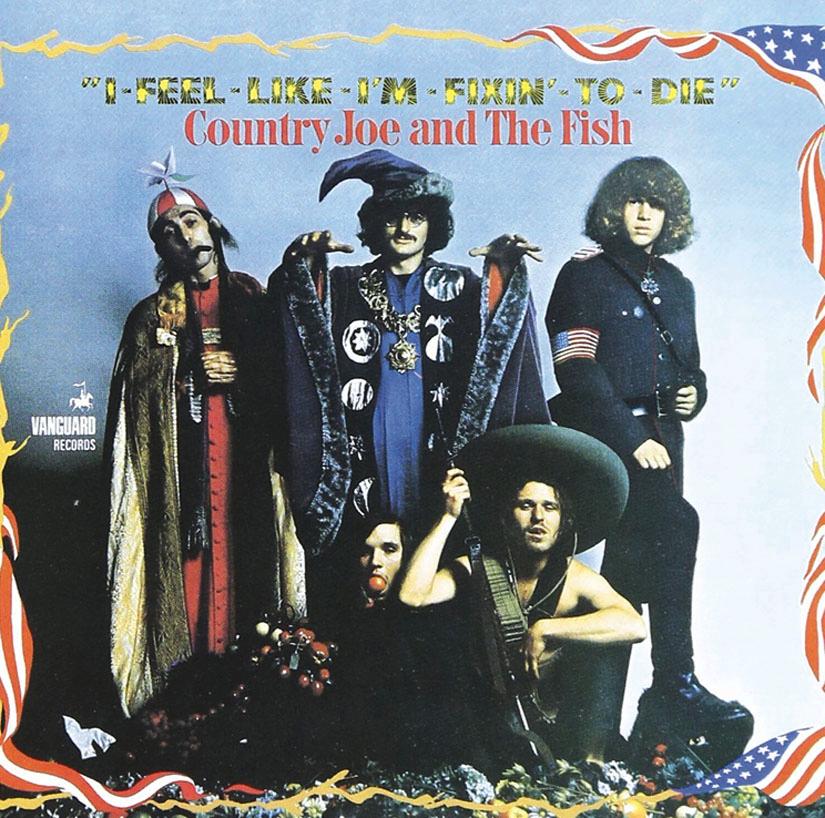

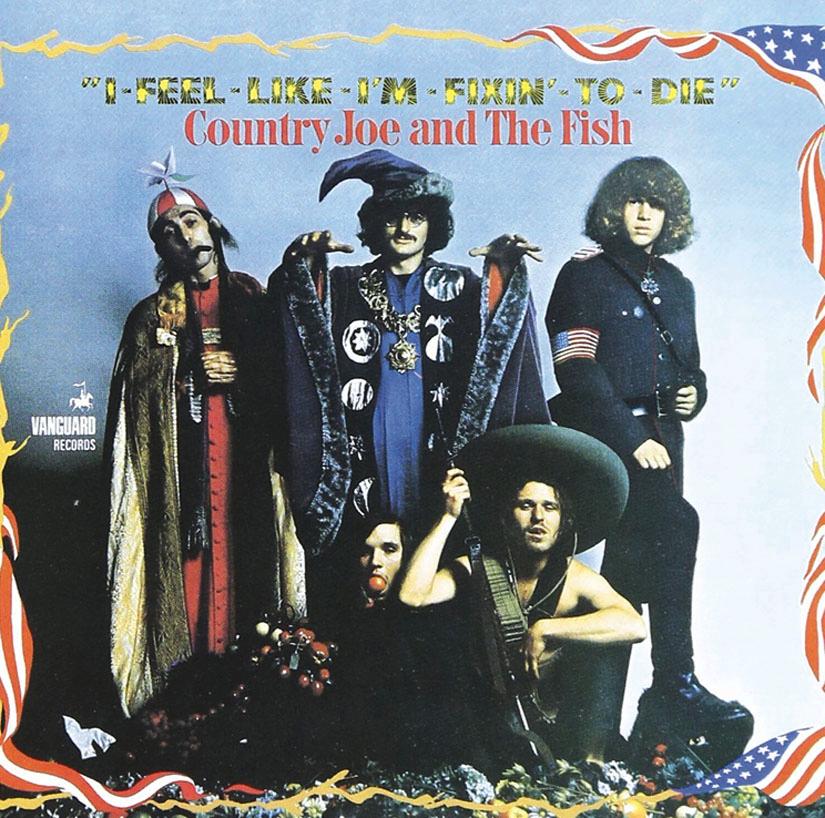

The second album Country Joe and the Fish album; Country Joe is seated front far right; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“Women coming home from the Vietnam War never were the same after their wartime experiences. They were shoved into a horrific, unbelievable experience. That’s what I wrote about in the song: ‘A vision of the wounded screams inside her brain, and the girl next door will never be the same.’” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: You first sang “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” on the streets of Berkeley during the Vietnam War in 1965. Fifty years later, you sang it at an anti-nuclear protest at Livermore Laboratory on the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Could you have imagined in 1965 that your song would still have so much meaning today?

Country Joe McDonald: Actually, I find the concept of 50 years incomprehensible. But it’s indisputable because I have children and some of those children have children and I know that the math is right. And I just finished an album and the title of it is 50 because it’s 50 years since the first album. It’s called Goodbye Blues. I didn’t die, so there you are. I’m still alive and I’m still doing something. Filling a need helps a lot, and it keeps me sane.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

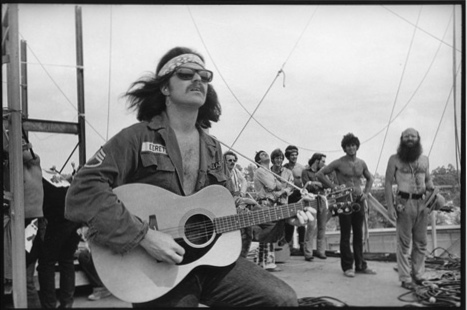

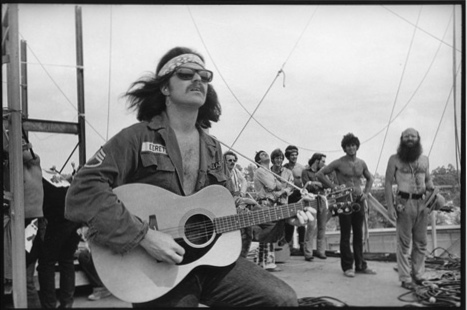

Country Joe McDonald sings “Fixin’ to Die Rag” for 300,000 people at Woodstock; photo by Jim Marshall, courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“It was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, London, and San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. It was a wonderful thing to happen. And I’m still a hippie: peace and love!” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: During the Vietnam War, and while caring for the victims of PTSD and Agent Orange in the years after the war, Lynda Van Devanter and other Vietnam combat nurses helped many veterans to survive. Your song about Van Devanter says that the combat nurse is everybody’s savior but her own. Then it asks, “Who will save her now?”

Country Joe McDonald: Yes, who will save her now?

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Country Joe McDonald sings anti-war songs; Livermore Lab, Hiroshima Day, August 6, 2015; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Country Joe McDonald composed one of the most acclaimed peace anthems of the Vietnam era, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” a rebellious and uproarious blast against the war machine. The song’s anti-war message seems more timely than ever, with its savagely satirical attack on the arms merchants, the military and the White House. “Fixin’ to Die Rag” condemns the architects of war and the military-industrial complex in bitterly sarcastic terms.

Come on Wall Street, don’t move slow

Why man, this is war au-go-go!

There’s plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade.

Recently, a major new book by Craig Werner and Doug Bradley, We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War, [Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015] ranked hundreds of Vietnam-era songs and listed “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” by Country Joe and the Fish as one of the two most important songs named by Vietnam veterans, right after “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” by the Animals. “The soldiers got it,” write co-authors Werner and Bradley about Country Joe’s song. Michael Rodriguez, an infantryman with the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, said: “Bitter, sarcastic, angry at a government some of us felt we didn’t understand — ‘Fixin’ to Die Rag’ became the battle standard for grunts in the bush.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

Anarcho-pacifist logo courtesy peaceofmindnews.com

The development of Christian Anarchism presaged the increasing convergence (but not complete merging) of pacifism and anarchism in the 20th century. The outcome is the school of thought and action (one of its tenets is developing thought through action) known as ‘pacifist anarchism’, ‘anarcho-pacifism’ and ‘nonviolent anarchism’. Experience of two world wars encouraged the convergence. But, undoubtedly, the most important single event to do so (although the response of both pacifists and anarchists to it was curiously delayed) was the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Ending as it did five years of ‘total war’, it symbolised dramatically the nature of the modern Moloch that man had erected in the shape of the state. In the campaign against nuclear weapons in the 1950s and early 1960s, more particularly in the radical wings of it, such as the Committee of 100 in Britain, pacifists and anarchists educated each other.

Read the rest of this article »

by William James

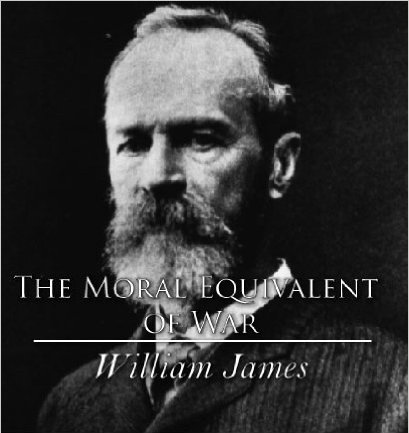

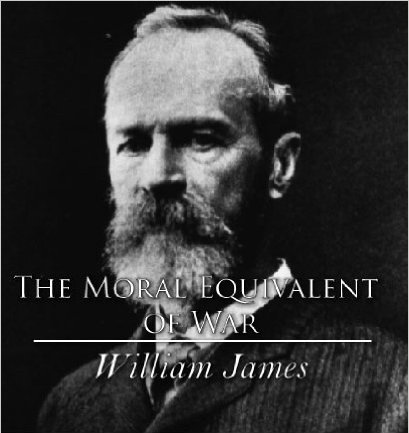

Cover art William James; courtesy charlesrivereditors.com

Editor’s Preface: William James delivered the first version of his famous essay at Stanford University in 1906. He was, in fact, asked to address a classic problem in political philosophy, sustaining political unity and civic virtue in the absence of war or in the threat of war. The text that follows adheres to the first published edition, McClure’s Magazine, August 1910, with our own grammatical corrections. JG

The war against war is going to be no holiday excursion or camping party. The military feelings are too deeply grounded to abdicate their place among our ideals until better substitutes are offered than the glory and shame that come to nations as well as to individuals from the ups and downs of politics and the vicissitudes of trade. There is something highly paradoxical in the modern man’s relation to war. Ask all our millions, north and south, whether they would vote now (were such a thing possible) to have our war for the Union expunged from history, and the record of a peaceful transition to the present time substituted for that of its marches and battles, and probably hardly a handful of eccentrics would say yes. Those ancestors, those efforts, those memories and legends, are the most ideal part of what we now own together, a sacred spiritual possession worth more than all the blood poured out. Yet ask those same people whether they would be willing, in cold blood, to start another civil war now to gain another similar possession, and not one man or woman would vote for the proposition. In modern eyes, precious though wars may be they must not be waged solely for the sake of the ideal harvest. Only when forced upon one, is a war now thought permissible.

Read the rest of this article »

by Stop Napalm Production Subcommittee

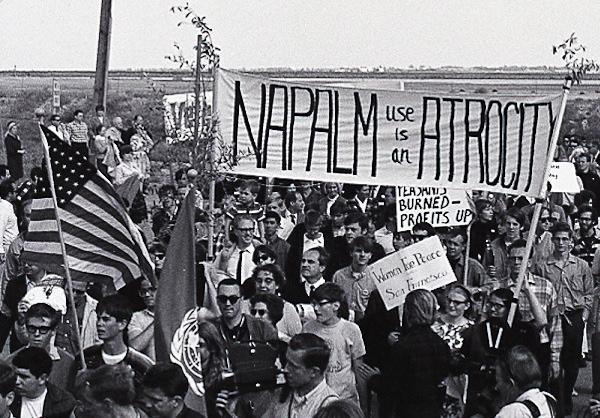

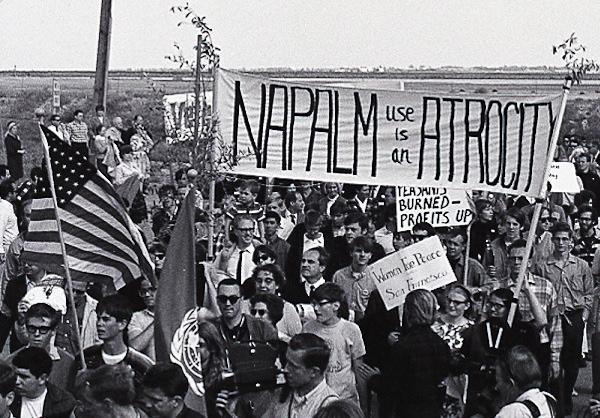

Napalm protest, 1966, photo by Harvey Richards; courtesy hrmediaarchive.estuarypress.com

Editor’s Preface: The Quaker Action Group convened a meeting in January of 1967 to discuss a nonviolent strategy for protesting the use of napalm in the Vietnam War. The two documents posted here in succession are unpublished internal memos outlining a strategy against Dow Chemical, the principle manufacturer of the deadly weapon. Among the members of the subcommittee were George Lakey, Lawrence Scott, and George Willoughby. These documents are especially noteworthy for their adherence to several Gandhian nonviolent civil disobedience principles, especially studying the opponent, and determining the weak point. They are another in our series of discoveries from the War Resisters’ International archive. Please see the note at the end for archival reference and acknowledgment. JG

You sit down to write a nice, dispassionate report on what napalm is. The paper is there, the pencils; all the facts you need to demonstrate the horror of this weapon. And you read this (New York Times, December 10, 1967):

“It comes premixed and packaged in thin-skinned aluminum tanks. There are three sizes of which the largest, a tank of 120 gallons weighing 800 pounds, and ten feet long and about three feet in diameter at its thickest point is most frequently used . . . About 1,500 tons of napalm are dropped in an average month in South Vietnam . . . Unlike conventional bombs most tanks of napalm are not provided with fins. Instead of spinning, they tumble, spreading the flaming fuel over an area in open country of about 150 feet along the path of the plane and about 50 feet wide.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Stop Napalm Production Subcommittee

Basic Assumptions

(1) The focus of the action will be on Dow Chemical Company, as the nation’s primary producer of napalm.

(2) The program will be carried out in step-by-step fashion, over a specific time period, and moving from less to more intense action steps.

(3) The action will be carried out in a variety of locations and should be as nearly nation-wide as possible.

(4) A Quaker Action Group will initiate and carry out the program in accordance with its nonviolent philosophy. Cooperation from other concerned groups is welcomed. Members of such groups, who are in accord with the nonviolent discipline, may be coopted onto the Napalm Strategy Committee of a Quaker Action Group.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

“The feminism that I believe in is a defense of all life. Not only women, not only the earth, but all together. It’s all reweaving the web.” Shelley Douglass

Jim and Shelley Douglass demonstrating for peace in Birmingham, Alabama.

Street Spirit: Concern for the rights of women, both in society and in the peace movement, was always a part of Ground Zero’s message to the larger movement. Can you describe how feminism and women’s issues became interwoven with Ground Zero’s peace work?

Shelley Douglass: Well, you have to remember that Ground Zero — and Pacific Life Community, which preceded it — were founded on the idea that nonviolence was a way of life. So it wasn’t just a political type of resistance campaign against Trident. It was an attempt, and is an attempt, to learn a new way of living where things like Trident are not necessary any more. In order to do that, you have to have justice, because the point of the weaponry is to defend things that are unjust or structures that are unjust. So equal rights for women was part of the basis of what we were doing.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Jim and Shelley Douglass with Seattle Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, c. 1980; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Street Spirit: I just read John McCoy’s new biography of Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, A Still and Quiet Conscience [Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2015]. He is such an inspiring man, but it was shocking to learn about the horrible indignities he suffered for speaking out for peace. Could you describe your impressions of the archbishop when he came to peace demonstrations at Ground Zero?

Shelley Douglass: He’s the kind of person you would never think was an archbishop, you know. You would never think of him as an archbishop or anybody with any power. I mean he’s just this guy, not particularly well dressed. When we knew him, he just seemed like this old guy and he was bald and had kind of a kindly persona. He listened a lot, and didn’t do a lot of talking.

I think that the first time I met him I was in jail. We had gotten arrested for committing civil disobedience and Jim and one other person in our group were both doing a fast. I don’t remember why the archbishop came to visit us in jail, but people were concerned about Jim’s safety, basically. I don’t know who got him to come, but he came, and even though he didn’t look or act like an archbishop, because he was the archbishop, the jail gave him a special visit. And they put Jim in a wheelchair and wheeled him down, and there was the archbishop!

Read the rest of this article »