by M. P. Mathai

Tree hugging photograph; courtesy spiritualecology.org

The ecological crisis we confront today has been analysed from various angles, and scientific data on the state of our environment are readily available. Humanity has come out of its foolish self-complacency and has awakened to the realisation that over-exploitation of nature has led to a very severe degradation and devastation of our environment. Scholars, through joint studies and research projects, have brought out the direct connection between consumption and environmental degradation. For example, professor of planning and development, Inge Ropke, has raised pertinent questions in his paper, “The Dynamics of the Willingness to Consume”: Why are productivity increases largely transformed into income increases instead of more leisure? Why is such a large part of these income increases used for consumption of goods and services with a relatively high materials-intensity instead of less material-intensive alternatives?

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Cover art courtesy vedicbooks.net

In a lecture given in 1993, the Indian historian Ramachandra Guha proposed to inquire whether Gandhi could be considered an “early environmentalist”. (1) Gandhi’s voluminous writings are littered with remarks on man’s exploitation of nature, and his views about the excesses of materialism and industrial civilization, of which he was a vociferous critic, can reasonably be inferred from his famous pronouncement that the earth has enough to satisfy everyone’s needs but not everyone’s greed. Still, when ‘nature’ is viewed in the conventional sense, Gandhi was rather remarkably reticent on the relationship of humans to their external environment. His name is associated with innumerable political movements of defiance against British rule as well as social reform campaigns, but it is striking that he never explicitly initiated an environmental movement, nor does the word ‘ecology’ appear in his writings. Again, though commercial forestry had commenced well before Gandhi’s time, and the depletion of Indian forests would persistently provoke peasant resistance, Gandhi himself was never associated with forest satyagrahas, however much peasants and rebels invoked his name.

Guha also observes that, “the wilderness had no attraction for Gandhi.” (2) His writings are singularly devoid of any celebration of untamed nature or rejoicing at the chance sighting of a wondrous waterfall or an imposing Himalayan peak; and indeed his autobiography remains utterly silent on his experience of the ocean, over which he took an unusually long number of journeys for an Indian of his time. In Gandhi’s innumerable trips to Indian villages and the countryside — and seldom had any Indian acquired so intimate a familiarity with the smell of the earth and the feel of the soil across a vast land — he almost never had occasion to take note of the trees, vegetation, landscape, or animals. He was by no means indifferent to animals, but he could only comprehend them in a domestic capacity. Students of Gandhi certainly are aware not only of the goat that he kept by his side and of his passionate commitment to cow-protection, but of his profound attachment to what he often described as ‘dumb creation’, indeed to all living forms.

Read the rest of this article »

by A. S. Sasikala

Silent Valley rainforest; photographer unknown; courtesy paradise-kerala.com

Environmental concerns were not much considered at the time of Gandhi, but his ideas on village decentralisation and national unity such as Swaraj, Swadeshi, Sarvodya, and especially the Constructive Programme makes him an advocate of environmentalism. He is generally considered to have had deep ecological views and his ideas have been widely used by different streams of environmentalism such as Green parties and the deep ecology movement founded by Arne Naess. The eminent environmental thinker Ramachandra Guha identified three distinct strands in Indian environmentalism, crusading Gandhians, ecological Marxists, and appropriate technologists, these last being advocates of small-scale, environmentally sound technology, most often known as “intermediate technology”. Guha observed that, unlike the third, the first two rely heavily on Gandhi, but Indian ecological Marxists also used Gandhian strategies and tactics. The Silent Valley Movement in Kerala, south India, is a case in point of just how ecological Marxists were willing to use Gandhian techniques in order to fight against environmental injustice. The role of the Marxist KSSP, Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (translated as Kerala Science Literature Movement, and also referred to as Kerala People’s Science Movement, PSM) illustrates their various strategies. Methodologies adopted throughout the movement were inspired by Gandhian methods, as previously used by other environmental movements like Chipko [see Mark Shepard’s article here].

Read the rest of this article »

by A. S. Sasikala

Poster courtesy greenpeace.org; artist unknown

We live in a world in which science, technology and development play important roles in changing human destiny. However, the overexploitation of natural resources for the purpose of development leads to serious environmental hazards. In fact, the idea of development is itself controversial, as in the name of development we are unethically plundering natural resources. It is rather common to encounter high dam controversies, water disputes, protests against deforestation, and against pollution. Eminent Indian environmental activist Vandana Shiva argues that development is actually a continuation of colonialism. Borrowing from Gustavo Esteva she argues that, “development is a permanent war waged by its promoters and suffered by its victims.” (1)

It is true that a science that does not respect nature’s needs, and a development that does not respect people’s needs threatens human survival. The green thoughts of Gandhi give us a new vision to harmonise nature with the needs of people.

Read the rest of this article »

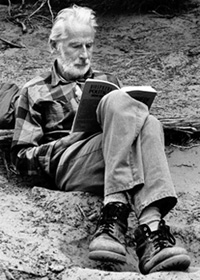

by Thomas Weber

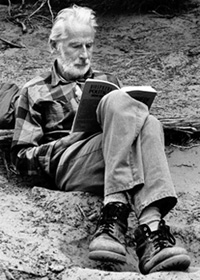

Arne Naess c. 2005; courtesy deepecology.org

The important philosopher of deep ecology and Gandhian philosophy, Arne Naess, died in January 2009. (1) Not one Australian newspaper or media outlet referred to this event. The news did not even make it into the obituary columns of such global weeklies as Time magazine (although, as usual, many sporting and film personalities did). Naess’s life was a significant one, and his philosophy still is. While environmentalists may know something about Naess’s thought, they tend to know little of its Gandhian antecedents. Those interested in Gandhian philosophy generally tend not to know of Naess’s contribution, but should. In short, Arne Naess should be remembered and his work examined.

A Personal Background

During 1996, as a Gandhi researcher and teacher of peace studies, I spent a few weeks as a visiting fellow at the Oslo Peace Research Institute. While in the city, I had decided to look up Arne Naess. I knew that in Norway he was an icon and that probably he had more environmentalists beating a path to his door than he needed. I, however, wanted to visit him because he had written one of the best (but least known) analyses of Gandhian nonviolence available in English – Gandhi and Group Conflict: An Exploration of Satyagraha. (2)

As a Gandhi scholar, I knew the Gandhi literature reasonably well and was often amazed to see learned articles on Gandhian philosophy that overlooked his book completely. Of course, this is the result of coming from a small out of the way country and having your landmark tome published by the Norwegian University Press. When I called on him, he was polite but seemed a little world-weary until I told him that I wanted to talk about the Mahatma because of his major contribution to Gandhi scholarship.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mark Shepard

Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s need, but not every man’s greed.

M. K. Gandhi

Chandi Prasad, 1978; photo by Mark Shepard

At the time of my India visit, I knew next to nothing about the rapid destruction of forests in Third World countries, or about its costs in terms of firewood shortage, soil erosion, weather shifts, and famine. Still, I was at once intrigued when I heard about the Chipko Movement, mountain villagers stopping lumber companies from clear-cutting mountain slopes by issuing a call to “hug the trees.”

So, one fall morning in 1978. along with a Gandhian friend, a young engineer, I found myself on the bus out of Rishikesh, following the river Ganges toward its source. Before long we had left the crowded plains behind and were climbing into the Himalayas. Thick forest covered the mountain slopes, interrupted only occasionally by terraced fields reaching dramatically up the mountainsides. Our bus bumped along a winding road halfway between the river below and the peaks above, as it followed the river’s meandering around the sides of mountains.

Read the rest of this article »

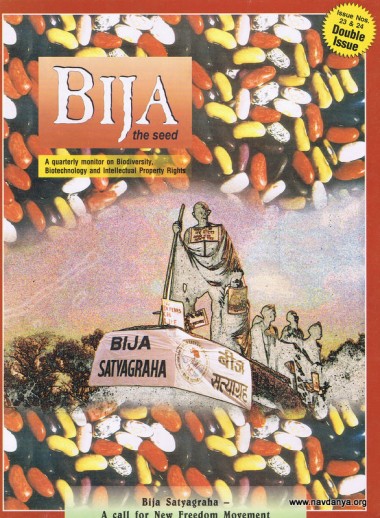

by the Navdanya Nine Seeds Movement

Editor’s Preface: This article inaugurates a series we shall be posting on contemporary movements and communities based on Gandhi’s Constructive Programme, which we are also posting in its entirety. For more information and links please consult our Editor’s Note at the end of the article. JG

Bija cover; artist unknown; courtesy of navdanya.org

Navdanya means “nine seeds”, (symbolizing protection of biological and cultural diversity) and also “new gift” (for seed as commons, based on the right to save and share seeds). In today’s context of biological and ecological destruction, seed savers are the true givers of seed. This gift, or “dhanya” and nava-dhanyas (nine seeds) is the ultimate gift, a gift of life, heritage and continuity. Conserving seed is conserving biodiversity, conserving knowledge of the seed and its utilization, conserving culture, and conserving sustainability.

Navdanya is also a network of seed keepers and organic producers spread across 17 states in India. It has helped set up 111 community seed banks across India, trained over 5,000,000 farmers in seed sovereignty, food sovereignty and sustainable agriculture over the past two decades, and helped establish the largest direct marketing, fair trade organic network in India. We have also founded a learning center, Bija Vidyapeeth (School of the Seed / Earth University) to teach biodiversity conservation, and we have an organic farm in Doon Valley, Uttarakhand, North India.

Navdanya is actively involved in the rejuvenation of indigenous knowledge and culture. It has created awareness of the hazards of genetic engineering, and defended people’s rights from bio-piracy and food rights in the face of globalisation and climate change. It is a women centred movement for the protection of biological and cultural diversity.

Read the rest of this article »

By Vandana Shiva

“Seed must be in the hands of the farmers”; photographer unknown; courtesy of seedfreedom.in

At a time when mega corporations want to control our food, it is imperative that we stand together to protect our food, the planet and each other.

In this earth

in this earth

in this immaculate field

we shall not plant any seeds

except for compassion

except for love. — Rumi

The Declaration on Seed Freedom

Seed is the source of life; it is the self-urge of life to express itself, to renew itself, to multiply, to evolve in perpetuity, in freedom.

Seed is the embodiment of bio-cultural diversity. It contains millions of years of biological and cultural evolution of the past, and the potential of millennia of a future unfolding.

Read the rest of this article »

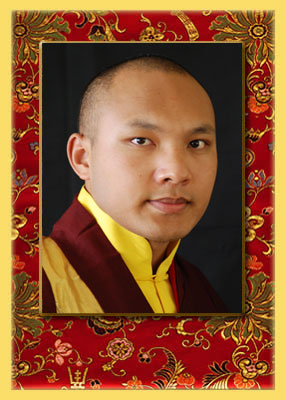

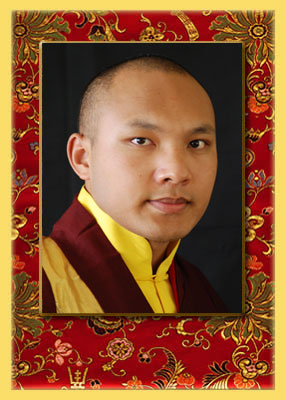

by Ogyen Thinley Dorje, His Holiness the 17th Karmapa

Ogyen Thinley Dorje; photographer unknown; courtesy of Karma Triyana Dharmachakra

Ever since the human race first appeared on this earth, we have used this earth heavily. It is said that 99% of our resources come from the natural environment. We are using the earth up. The earth has given us immeasurable benefit, but what have we done for the earth in return? We always ask for something from the earth, but never give her anything back. We never have loving or protective thoughts for the earth. Whenever trees or anything else emerge from the ground, we cut them down. If there is a bit of level earth, we fight over it. To this day we perpetuate a continuous cycle of war and conflict over it. In fact, we have not done much of anything for the earth. Now the time has come when the earth is scowling at us; the time has come when the earth is giving up on us. The earth is about to treat us badly and give up on us. If she gives up on us, where can we live? There is talk of going to other planets that could support life, but only a few rich people could go. What would happen to all of us sentient beings who could not go?

What should we do now that the situation has become so critical? The sentient beings living on the earth and the elements of the natural world need to join their hands together—the earth must not give up on sentient beings, and sentient beings must not give up on the earth. Each needs to grasp the other’s hand. So doesn’t the Monlam logo look like two hands clasping each other?

Dream Flag design; courtesy of khoryug.com

Its shape is similar to the design of the Sixteenth Gyalwang Karmapa’s Dream Flag, of peace and serenity, which is used regularly among the Karma Kamtsang tradition. If I were to make up everything myself, I doubt it would have any blessings, but using the previous Karmapa’s design as a model probably gives this logo blessings. This is a symbol of our Kagyu Monlam that we hold for the benefit of the entire world. We will not give up on the earth! May there be peace on earth! May the earth be sustained for many thousands of years! These are the prayers we make at the Kagyu Monlam, which is why this symbol is the logo of the Monlam. (1) I think it also might become a symbol of people having affection for the earth and wanting to protect it.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bharat Mansata

Bhaskar Save on 92nd birthday; photograph by the author

Bhaskar Save, acclaimed “the Gandhi of Natural Farming”, turned 92 on 27 January 2014, having inspired and mentored three generations of organic farmers. Masanobu Fukuoka, the legendary Japanese natural farmer, visited Save’s farm in 1996, and described it as “the best in the world”, ahead of his own farm. In 2010, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) honoured Save with the “One World Award for Lifetime Achievement”.

Indeed, Save’s farm is a veritable food forest; a net supplier of water, energy and fertility to the local eco-system, instead of a net consumer. His way of farming and his teachings are rooted in a deep understanding of the symbiotic relationships in nature, which he is ever happy to explain in simple, down-to-earth idioms to anyone interested. Save’s 14 acre orchard-farm Kalpavruksha is located on the Coastal Highway near village Dehri, District Valsad, in southernmost coastal Gujarat, a few km north of the Maharashtra-Gujarat border. The nearest railway station is Umergam on the Mumbai-Ahmedabad route.

Read the rest of this article »