by Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb

Peace mural Shomer Shalom; courtesy shomershalom.org

Author’s Preface: Sami Awad is a Palestinian Christian from Bethlehem, and the nephew of Mubarak Awad, one of the founders of the Palestinian nonviolent movement. [See the interviews we have posted with Mubarak Awad.] When still a boy his uncle gave him the writings of Gandhi, which led to a lifelong commitment to Gandhian nonviolence. Upon finishing his studies in the U.S. he returned to the Palestinian Territories and in 1998 founded The Holy Land Trust, the mission of which is “to create an environment that fosters understanding, healing, transformation, and empowerment of individuals and communities . . . in the Holy Land.” Awad is one of thousands of people in Palestine who resist occupation every day through nonviolent popular resistance. Holy Land Trust works with the Palestinian community at the grassroots and leadership levels in developing nonviolent approaches to Israeli-Palestinian conflict transformation and a future founded on the principles of nonviolence, equality, justice, and peaceful coexistence. Awad has also established the Travel and Encounter Program, which aims to provide tourists and pilgrims with unique religious and political experiences in Palestine, and the Palestine News Network, the first independent press agency in Palestine and a major source of news on life in Palestine today. RLG

Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb: Ahlan wa sahlan, Sami. Nonviolent civilian resistance to foreign occupation has been a way of life in Palestinian society. The words sumud (steadfast) and intifada (shaking off) describe the nature of Palestinian nonviolence. Can you give us a thumbnail sketch of the history of Palestinian nonviolent civilian resistance and the popular struggle?

Read the rest of this article »

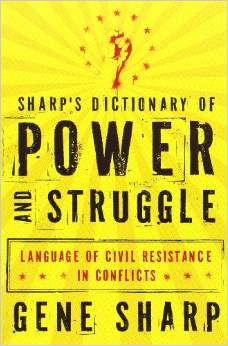

by Metta Spencer

Book jacket courtesy Oxford University Press; global.oup.com

Metta Spencer: It has been eight years since I last interviewed you for the magazine. Since then people around the world have begun to listen to you.

Gene Sharp: Yes, I was just now invited to a Washington journal — Foreign Policy — who will publish something about people who had some response in the world in the last year. That kind of invitation never happened a few years ago.

Spencer: I know. In fact, let’s begin by reviewing the changes in your own thinking. As I recall, you started off as a graduate student in sociology working on a masters thesis and have managed to turn into Gene Sharp, the guy on the front page of the New York Times. Let’s start at the time when you began to realize that nonviolence was a special set of practices that could be developed into useful procedures.

Sharp: Ah yes! One thing that was in the master’s thesis was a typology of nonviolence. I classified six or seven belief systems, of which one was called “nonviolent resistance.” That’s a different category but it was in with the others. (Today I don’t even like the term “nonviolence” except for very special uses.) That typology went through several revisions and one was published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, which was an entirely new publication at the time. In it I took out nonviolent struggle as a separate category. That was a breakthrough in my thinking — that people didn’t have to have the belief in order for them to act.

I remember one time in the basement of the Ohio State University library. I was looking through old Indian newspapers on the conflict — I think it was the 1930 campaign — and the evidence was there: These people did not believe in nonviolence as an ethic! That was a shock. I thought: Oh dear! We didn’t have copy machines then. I had to copy the whole thing by hand and I thought; should I copy that down? It’s not supposed to be that way. But my focus on reality won out, fortunately, and I copied it down. Later I realized that it wasn’t a problem. It was a breakthrough, an opening! People didn’t have to believe in order to use this form of action! Therefore, it was open to almost everybody. That breakthrough was in about 1950 or ’51.

Read the rest of this article »

by Meir Amor

Meir Amor: About 15 years ago you and I had a discussion that was published in Peace Magazine. The editors of Peace think it would be good to have another talk. So let me ask you first: Does your approach to nonviolence have a religious basis? Do Jewish or Muslim religious authorities consider it compatible with their teachings?

Photo of Mubarak Awad, 2014, by Meir Amor; courtesy nonviolenceinternational.net

Mubarak Awad: Personally, I do it from a Christian perspective. For me, it’s time for us all to learn not to kill or destroy. But I did not push that belief on any Israelis or any Muslims. However, I did study Islam and nonviolence a lot, and I thought it would be great to have a Muslim who was interested in nonviolence so we could have a strong campaign. At that time I was interested in Faisal Husseini (1), a great Muslim who believed in nonviolence. I bought a lot of books about a Muslim who had been with Gandhi — Abdul Ghaffer Khan (2), who said that Islam is a nonviolent religion. I was doing that because the majority of Palestinians are Muslim. We held conferences studying Islam and nonviolence — discussing what jihad really means and Sufism in Islam. Sufis are like the Quakers in Christianity; they believe in peace.

There are many Sufis in Islam, who accept the challenge of nonviolence. It’s a big struggle for them — not only between the Palestinians and Israelis or Arabs and Israelis, but also between themselves, for them to be nonviolent at home and active in nonviolence in their community. They can see that we human beings have brains, not just guns, and can resolve any conflict, however big, by debating, by forgiveness, by conciliation.

But in the past twenty years the world has moved toward radical religion in Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. That allows a minority within each religion to start dictating what religion means in a fundamentalist way. Many Muslims want to go back to a caliphate or to Mohammed. Some of them want to be more fundamentalist or more conservative.

Read the rest of this article »

by Meir Amor

Palestinian nonviolence marchers, Bil'in Village. Credit: Creative Commons/Michael Loadenthal; courtesy tikkun.org

Meir Amor: Why did you become a leader in the nonviolent Palestinian struggle?

Mubarak Awad: Palestinians had hardly any understanding of nonviolence. Gandhi had not been given a lot of attention in the Muslim world because he was against the creation of Pakistan, an Islamic state. So in the Arab mind nonviolence is just surrendering to the one who has more power.

Before I was expelled from Israel in 1988, my first initiative with Palestinians was to try to develop an educational program of nonviolence in Islam. I went to India to find a Muslim who worked with Gandhi: Abdul Ghaffar Khan, (1) who brought his village of Pathans into a struggle, forming a nonviolent army to help Gandhi. I wrote a book about him and met with religious leaders in Palestine, Israel, and Egypt. I found interested Muslims — most of them Sufis. In Islam, the Sufis are like Quakers in Christianity. In some places they are regarded as heretics. They pray; they dance; they act as if they have oneness with God. In Islam you cannot do that, so the Sunnis and Shiites don’t accept them as real Muslims. They are the ones who started writing about Islam and nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

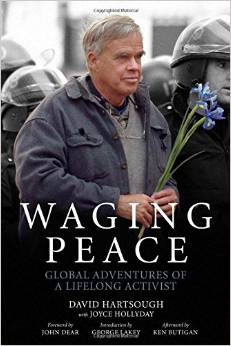

by Terry Messman

Covert art courtesy PMPress.org

Street Spirit: Looking back at a lifetime of nonviolent activism, can you remember the first person who helped set your life on this path?

David Hartsough: Gandhi. My parents gave me Gandhi’s book, All Men Are Brothers, on my 14th or 15th birthday. And Martin Luther King who I met when I was 15.

Spirit: Why was Gandhi’s All Men Are Brothers such an inspiration?

Hartsough: Because he said that nonviolence is the most powerful force in the world, and he believed that, and he practiced it. His entire life was made up of his experiments with nonviolence, his experiments with truth. He took nonviolence from being kind of a moral, theological, philosophical idea, and showed it could be a means of struggle to liberate a country. That was a great model for me that nonviolence is not just morally superior to killing people, but was a more effective way of liberating people. Also, his belief that all people are children of God. We are all one. We’re not black versus white, Americans versus Russians, good guys versus bad guys. We’re all brothers and sisters. I took that seriously and that’s what I believe.

Spirit: What was your first involvement in a social-change movement as a young activist?

Hartsough: When I was 14, there was a Nike missile site near where I lived in Philadelphia. This was when people were hiding under their desks in school or going into air raid shelters to try to be safe when we had a nuclear war — which is absolutely ridiculous. So I organized other young people to have a vigil at this Nike missile site over Thanksgiving. We fasted and we walked around with our picket signs in front of the place, and that’s where my FBI record started.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Logo courtesy of www.nonviolentpeaceforce.org

“Governments have the power to throw us in jail and shoot at us and intimidate us,

but they don’t have the power to kill our spirits.” David Hartsough

Spirit: David, when were you hired as staff organizer for the American Friends Service Committee in San Francisco?

Hartsough: I was hired in 1973 to be part of the Simple Living Program. My wife Jan and I shared the staff position. Then I began the American Friends Service Committee [AFSC] Nonviolent Movement Building Program in 1982.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Kelly with Afghan peace volunteers; photographer unknown; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“The people that threaten us are in the corporations and the well-appointed salons,

and they really threaten us. They make alcohol, firearms and tobacco,

and arms for the military.They steal from us, and they rob us. And who goes to jail?

A woman who can’t get an economic stake in her community.” Kathy Kelly

Street Spirit: You just returned from Afghanistan last month where you were living with the Afghan Peace Volunteers. Many people, even in activist circles, are no longer focusing on that war-torn nation. Why does Afghanistan remain such a critical focus of your work?

Kathy Kelly: I have a friend, Milan Rai, who had coordinated Voices in the Wilderness in the U.K. and is now the editor of Peace News. Mil once said, “One of the ways to stop the next war is to continue to tell the truth about this war.”

So how do we tell the truth about our wars? I think if the U.S. public understood the choices that are being made in their name — and if the public understood those choices outside the filter of the forces that are marketing those wars — eventually there might be a hope of non-cooperation with wars.

So Afghanistan is still very, very important in terms of the choices confronting the people of the United States. But also, just on the purely ethical matter of not turning away from people who are dying, we owe reparations to the people of Afghanistan for the suffering that has been caused.

Read the rest of this article »

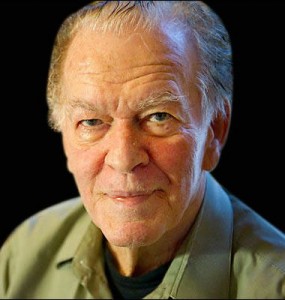

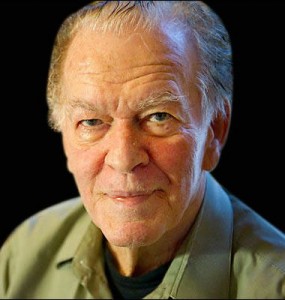

by Amitabh Pal

Gene Sharp, 2012; photographer unknown; courtesy of tarata21.com

Gene Sharp is perhaps the most influential proponent of nonviolent action alive. His work has served as a how-to manual for activists in a swath of countries across Eastern Europe and Asia. For instance, From Dictatorship to Democracy and The Politics of Nonviolent Action helped inspire the Serbian student movement that toppled Slobodan Milosevic in 2000.

Sharp writes, “Nonviolent action is possible, and is capable of wielding great power even against ruthless rulers and military regimes, because it attacks the most vulnerable characteristic of all hierarchical institutions and governments: dependence on the governed.”

Sharp drafted From Dictatorship to Democracy at the invitation of a Burmese activist. He was smuggled into Burma to assist in courses on nonviolent struggle for those resisting the military regime. He was in Tiananmen Square shortly before the tanks started rolling in. He has traveled to Israel and Palestine a number of times to disseminate his ideas. He was also invited into Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, this time by the governments themselves. He consulted with ministers on the nature and requirements of the campaign that they were using to peacefully secede from the Soviet Union. The three governments also used as a guide his book Civilian-Based Defense. The three countries became sovereign with almost no loss of life.

Read the rest of this article »

by Nina Koevoets

Nonviolent resistance constitutes an influential idea among idealist social movements and non-Western populations, one that has moved to center stage in recent events in the Middle East. Mary King has spent over 40 years promoting nonviolence through her involvement in the women’s movement, nonviolence studies, and civil action.

Theory Talks: What is, according to you, the central challenge or principal debate in International Relations? And what is your position regarding this challenge, in this debate?

Mary King at the University for Peace; photographer unknown

Mary Elizabeth King: The field of International Relations (IR) is different from Peace and Conflict Studies; it has essentially to do with relationships between states and developed after World War I. In the 1920s, the big debates concerned whether international cooperation was possible, and the diplomatic elite were very different from diplomats today. The roots of Peace and Conflict Studies go back much further. By the late 1800s peace studies already existed in the Scandinavian countries. Studies of industrial strikes in the United States were added by the 1930s, and the field had spread to Europe by the 1940s. Peace and Conflict Studies had firmly cohered by the 1980s, and soon encircled the globe. Broad in spectrum and inherently multi-disciplinary, it is not possible to walk through one portal to enter the field.

Read the rest of this article »

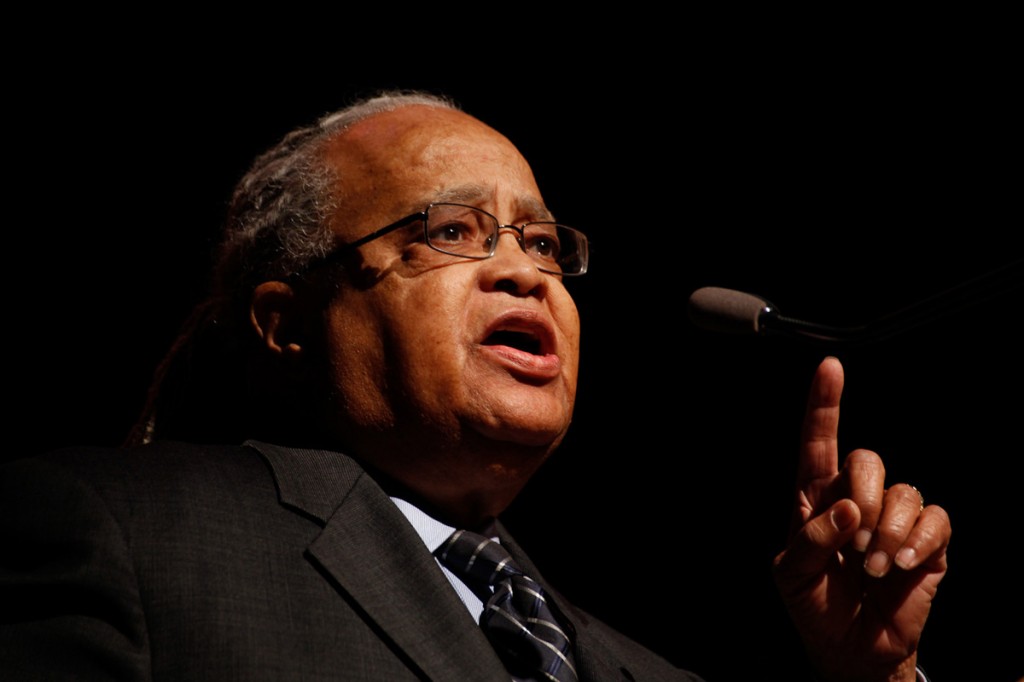

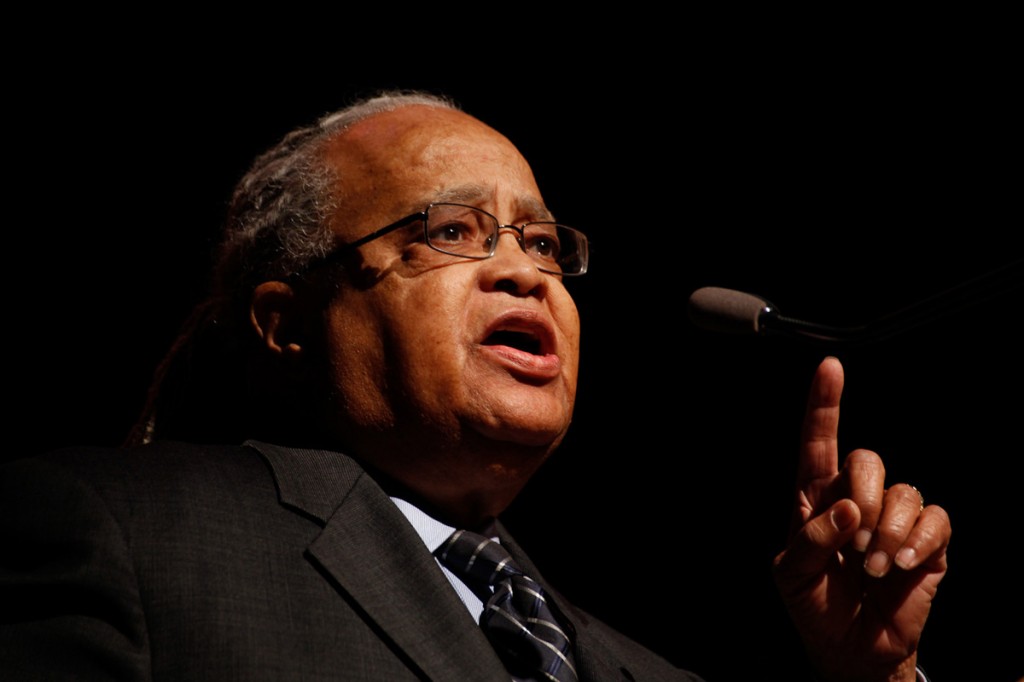

by Terry Messman

Rev. Phillip Lawson, c. 2012; photographer unknown

“Love and compassion are what sustain me. Love and you can learn how to live. I told the Council of Elders this. When you are down and depressed, or hurting or grieving, the most powerful thing you can do to sustain yourself is to go do something for someone else who is hurting.” Rev. Phil Lawson.

Street Spirit: Rev. Lawson, you told me that when you were growing up, you realized that horrific violence was directed against the black community — Jim Crow laws, segregation, lynching. In the face of that violence, why did you make a commitment to nonviolence at age 15 that has lasted for the past 65 years?

Nonviolence is a way of life that leads to community.

Rev. Phil Lawson: I’m firm in my understanding and beliefs, Terry, that nonviolence is a way of life. Rather than a tactic or a strategy to overcome problems, nonviolence is a way of life that leads to community. You cannot build community on violence, whether it’s psychological violence, economic violence, cultural or environmental violence. Regardless of the adjective you put before the word “violence,” violence will not produce community. And the goal of my life, and I think for most human beings, is community. The opposite of slavery is not freedom, but community. The opposite of abuse and oppression is not just to be free of that, but to live in a community where that abuse is infrequent, where that is not supported, where that is not structural. We live in a nation in which violence is structural; it is not personal. Racism is structural.

Read the rest of this article »