by Anil Nauriya

When I am contradicted it arouses my attention, not my wrath.

I move towards the man who contradicts me: he is instructing me.

The cause of truth ought to be common to us both. Montaigne

The debates on Gandhi’s role as a personality and as a symbol of Indian nationalism will go on; the purpose of this article is mainly to draw attention to some points of methodology which, when overlooked, lead to erroneous and even absurd results.

First, analysis confined to comparing the positions of any individuals or organizations at a single arbitrarily chosen point in time is inadequate. Gandhi as well as his critics were continually evolving. The movement in their positions is often of more significance than their points of view at any isolated moment.

Read the rest of this article »

by Sean Chabot

Dust jacket courtesy Oxford University Press; global.oup.com

In her preface to the 1965 edition of Conquest of Violence (see References at the end), Joan Bondurant makes a strong case for distinguishing nonviolent action as duragraha or Gandhian satyagraha. She argues that duragraha involves pressuring opponents based on a de facto prejudgment that they are wrong, through passive resistance, and through symbolic violence. In a later essay (posted previously here), she adds that it is a form of stubborn or willful resistance seeking to demonstrate that opponents are necessarily wrong; that resisters are inherently righteous; and that the purpose of nonviolent action is to gain predetermined objectives by winning battles with opponents. In contrast to satyagraha (i.e., firmness in seeking truth through the power of love), duragraha aims at gaining tangible concessions from power-holders in the short-term rather than transforming social relationships and creating in the long run alternative ways of life benefiting everyone, especially the most oppressed. Bondurant emphasizes these distinctions, because she feels that most of the so-called Gandhian struggles during the 1960s are actually examples of duragraha, not satyagraha. In her eyes, this misunderstanding severely limits the political, ethical, and transformative potential of these struggles.

In the 1960s, Gene Sharp—the undisputed pioneer of nonviolent action and civil resistance studies—responded very differently to Gandhi’s legacy. Unlike Bondurant, Sharp invokes Gandhi to define nonviolent action as “a technique used to control, combat and destroy the opponent’s power by nonviolent means of wielding power”, without carefully conceptualizing satyagraha or considering how it diverges from duragraha (Sharp 1973: 4). By erasing these differences, and by focusing on conventional power politics instead of situational ethics, his The Politics of Nonviolent Action articulates a generic and simplistic understanding of nonviolent action that applies to many cases of unarmed resistance throughout history and across the world. In the process, he normalizes duragraha as a pragmatic and strategic form of nonviolence, thereby hollowing out Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha while continuing to use Gandhi’s name to popularize his own approach. Since the 1970s, Sharp has quickly become the most influential figure in the field, serving as mentor to fellow civil resistance authors like George Lakey, Peter Ackerman, Jack Duvall, Michael Randle, Howard Clark, April Carter, and of course Mary King.

Read the rest of this article »

by Chandi Prasad Bhatt

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished paper, from the War Resisters’ International archive, was presented at the Nonviolence and Social Empowerment conference held in Orissa, India, February 2001. Further biographical information, acknowledgments, and archival reference can be found at the end. See also Mark Shepard’s article about Bhatt and Chipko, posted here at this link. JG

Photograph of Bhatt courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of self-governance (swaraj) aimed to create an egalitarian society. To achieve it, a committed group of people established Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal (Society for Village Self-Rule; DGSM) at Gopeshwar, northern India, in 1964. Since the objective was to develop a self sustaining nonviolent society, training was offered in village industries, agriculture, horticulture, animal husbandry, harvesting forest produce, utilizing mineral resources, employment in various construction activities, educating and awakening people for forest protection, husbanding of natural resources, etc. Gradually, DGSM become a symbol of village self-reliance. However, everything changed in 1970 when a massive flood hit the Alaknanda river basin, devastating the normal life and destroying the property. The flood was unprecedented in the history of the region, and was described by the government as a natural calamity. But the relief workers of DGSM refused to accept this, as they had witnessed the destruction of the forests between 1950-1970 in the watersheds from where the flood originated. While undertaking the relief operation in the flood-affected watersheds, DGSM volunteers concluded that the flood was more man-made than claimed.

Read the rest of this article »

by Stephan Brües

Youths in Ecuador painting peace symbols; courtesy wagingnonviolence.org

Editor’s Preface: We have previously posted, from the War Resisters’ International archive, two historical articles about nonviolent resistance in Latin America, which can be accessed at this link. This article updates the information, and the struggle. Please consult the Editor’s Note at the end for further biographical information and acknowledgments. JG

Blas Garcia Noriega, a small man who wears glasses, is thoughtful and vivid, especially when he talks about his activities with Servicio Paz y Justicia, or SERPAJ. Founded 40 years ago in Medellin, Colombia, SERPAJ promotes nonviolent resistance and peaceful conflict resolutions throughout Latin America.

“SERPAJ is not an NGO, but a social movement,” Garcia said. “We are doing big things with little resources.” In words like these, it is possible to hear the challenges of this kind of work and the pride he takes in doing it. Peace activists like Garcia who oppose all forms of violence — whether from the state, guerrillas, drug sellers or militias — are caught between many armed groups in Colombia.

Read the rest of this article »

by Hildegard Goss-Mayr

Brazilian farmers’ nonviolent land protest; courtesy mettacenter.org

Editor’s Preface: The following, previously unpublished essay was presented to the Alternative Defense Commission, as part of the War Resisters’ International Peace Education Project, c. 1987. It continues our series of discoveries from the WRI archive. Please see the notes at the end for archival reference, as well as acknowledgment and biographical information about the author. JG

In most Latin American countries military or civilian dictatorships, on the basis of the doctrine of national security, continue to uphold an economic system of exploitation that favors a small group of privileged individuals (as well as national and multinational corporations in the First World) and condemns the vast majority of the people to a life of dependence, misery, and political and social marginalization. But the masses of the poor in Latin America have increasingly become aware of their human rights and dignity, and in many parts of the continent, despite violent and brutal repression, they have begun to organize and struggle for change. Popular civic movements are springing up and pressing for justice.

Read the rest of this article »

by Matt Meyer

Book jacket art courtesy wipfandstock.com

Editor’s Preface: The following, previously unpublished essay was presented to the Alternative Defense Commission, as part of the War Resisters’ International Peace Education Project, c. 1987. It continues our series of discoveries from the WRI archive. Please see the notes at the end for acknowledgment, archival reference, and biographical information about the author. JG

To many western activists it may seem that revolution and nonviolence are clear contradictions. Nonviolence is often seen as passive, utopian, naive, or as a bourgeois luxury that we in the West arrogantly urge upon our Central American sisters and brothers. However, revolutionary nonviolence is not passive, reformist, or romantic. It is a powerful means of social change, which confronts the roots of militarism; its use in Central America has often been ignored.

Western pacifists may well be challenged about their commitment to nonviolence even in the war zones of Central America. “What do you know?” someone might ask. What we know, and what we believe history has taught us, is that revolution is a long process, with many difficult questions and no easy answers. We know that to strive for an end to war, we must first struggle for the elimination of the causes of war, including racism, sexism, class structures, and imperialism. We know that any revolution, including nonviolent revolution, will suffer bloodshed and innocent casualties, and we continue to experiment with diverse forms of resistance to minimize bloodshed and maximize lasting social change. Above all, we know that we cannot begin to talk about nonviolent revolution until we place ourselves firmly in solidarity with those already in revolutionary struggles throughout the world.

Read the rest of this article »

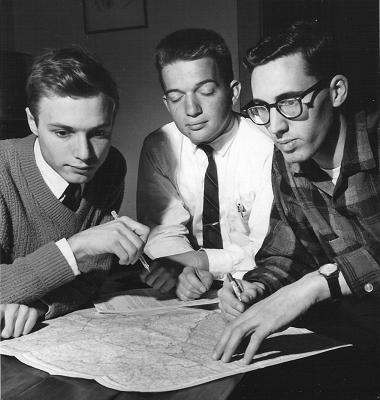

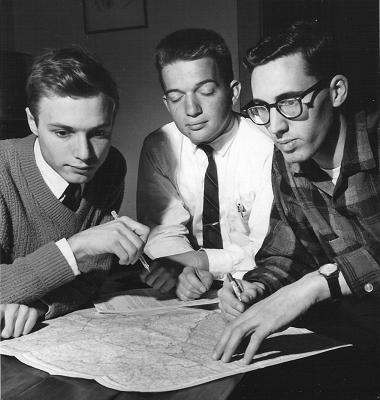

by Gene Keyes

Gene Keyes, Dennis Weeks, and Joe Tuchinsky planning 1964 civil rights march route to Albany, Georgia

Editor’s Preface: The topic of nonviolent civilian defense was high on the agenda of the peace and nonviolence movements in the 1970s and 1980s. This essay is representative of that discussion, and is another in our series of discoveries from the War Resisters’ International archive. The article appears to be Chapter Two of the author’s “unpublished” PhD thesis for Toronto University; a pdf scan of the original is attached. Please also consult the notes at the end for archival reference, acknowledgment, biographical information about the author, and a link to his site. JG

The idea we are considering has had numerous names since the 1850s, and especially since the 1950s: passive resistance; nonresistance; nonviolent resistance; civil resistance; unarmed defense; nonviolent defense; nonmilitary defense; civilian defense; civilian resistance; nonviolent civilian defense; social defense; civilian-based defense; societal defense; post-military defense; etc..

An expression I would like to try out is “common defense,” but reinvigorated to mean an effort mounted by an entire polity using the nonviolent means at hand; with defiance and organization; with strategy, principle, and tenacity: common defense of everyone, by everyone, for everyone; common defense without nuclear weapons, firepower, or any other killing and violence; common defense as workaday resistance by an unconquerable free people.

Read the rest of this article »

by Gene Sharp

Editor’s Preface: The manuscript of this unpublished essay is not dated, but based on the dating of other material in the same folder, is c. 1962. It is another in our series of discoveries from the War Resisters’ International archive, which we have been researching for the last year. An archive reference, acknowledgments, and a note about Sharp are at the end. JG

The Indian government and people have responded to the Chinese use of armed force to adjust the border between their countries with war preparations and reliance upon military means to deal with the foreign threat. The Indian reaction has for many people in the peace movement, and pacifists in particular, been something of a shock. Many of these believe that India has somehow let them down, that she has failed to live up to the moral challenge imposed in different ways both by Gandhi and by the nature of modern war.

Read the rest of this article »

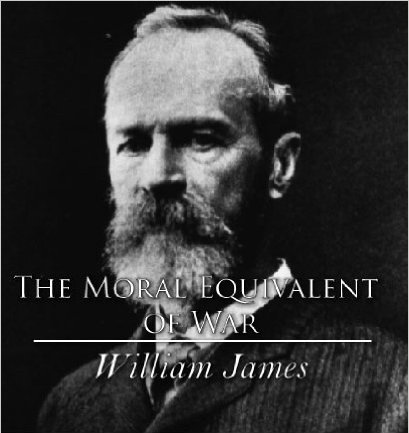

by William James

Cover art William James; courtesy charlesrivereditors.com

Editor’s Preface: William James delivered the first version of his famous essay at Stanford University in 1906. He was, in fact, asked to address a classic problem in political philosophy, sustaining political unity and civic virtue in the absence of war or in the threat of war. The text that follows adheres to the first published edition, McClure’s Magazine, August 1910, with our own grammatical corrections. JG

The war against war is going to be no holiday excursion or camping party. The military feelings are too deeply grounded to abdicate their place among our ideals until better substitutes are offered than the glory and shame that come to nations as well as to individuals from the ups and downs of politics and the vicissitudes of trade. There is something highly paradoxical in the modern man’s relation to war. Ask all our millions, north and south, whether they would vote now (were such a thing possible) to have our war for the Union expunged from history, and the record of a peaceful transition to the present time substituted for that of its marches and battles, and probably hardly a handful of eccentrics would say yes. Those ancestors, those efforts, those memories and legends, are the most ideal part of what we now own together, a sacred spiritual possession worth more than all the blood poured out. Yet ask those same people whether they would be willing, in cold blood, to start another civil war now to gain another similar possession, and not one man or woman would vote for the proposition. In modern eyes, precious though wars may be they must not be waged solely for the sake of the ideal harvest. Only when forced upon one, is a war now thought permissible.

Read the rest of this article »

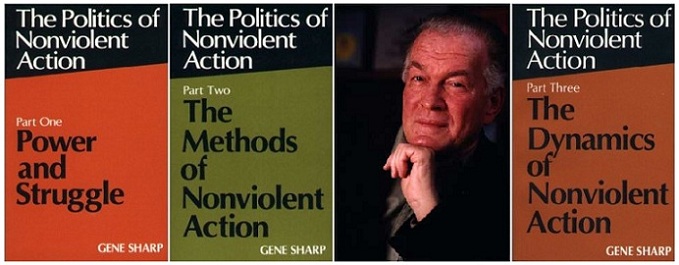

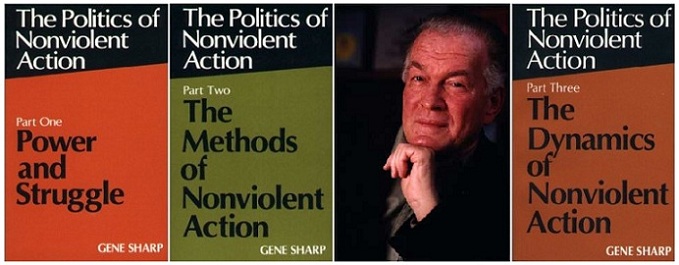

by Gene Sharp

Book jacket assemblage courtesy rcnv.org

Editor’s Preface: This little known essay by Gene Sharp was discovered in the War Resisters’ International archive in a folder labeled “Ira Sandperl’s Speaking Tour of Western Europe, 1970: Background Reading.” The typescript seems to have been given to Sandperl by Sharp. We have not found any evidence that Sharp published the essay in this form, although he was to rework the material in later works, especially the section below “84 Cases of Nonviolent Action”. Sandperl was an interesting figure in the 1970s peace movement. A foremost member of the War Resisters League, (the U.S. branch of WRI), he might be better known to some as Joan Baez’s acknowledged mentor. Sandperl was also co-founder of the Peninsula Peace Center in California, which Baez also helped support. Please see the notes at the end for further information about Gene Sharp, archival references, and acknowledgments. JG

It is widely believed that military combat is the only effective means of struggle in a wide variety of situations of acute conflict. However, there is another whole approach to the waging of social and political conflict. Any proposed substitute for war in the defense of freedom must involve wielding power, confronting and engaging an invader’s military might, and waging effective combat. The technique of nonviolent action, although relatively ignored and undeveloped, may be able to meet these requirements, and provide the basis for a defense policy.

Read the rest of this article »