by Geoffrey Ashe

Dustwrapper art courtesy Stein & Day Publishing

Editor’s Preface: Gandhi was born in 1869 and as the centennial year of 1969 approached, pacifist and other publications worldwide used it as the occasion to re-evaluate Gandhi’s importance. The British cultural historian Geoffrey Ashe’s biography of Gandhi had been published to acclaim in early 1968 and Peace News published this article in their 16 August 1968 issue. It is the latest in our series of rediscoveries from the archives of the IISG in Amsterdam. Please see the notes at the end for references, acknowledgments, and further biographical information about Ashe. JG

Several months ago, Joan Baez described nonviolence as a flop, although she did qualify that by saying violence was a bigger flop. However, to my mind, we shouldn’t be downcast. By studying Gandhi’s nonviolence a little more carefully we can see what was right and wrong and make a fresh start. I am working on the Gandhi Centenary because I believe that some of the ideas which Gandhi explored in his career are still valuable and exciting, uniquely so; that these ideas can be restated and reapplied in the present context; but – what is perhaps the main thing – that no large-scale movement in this country has yet fully absorbed them or put them into practice.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

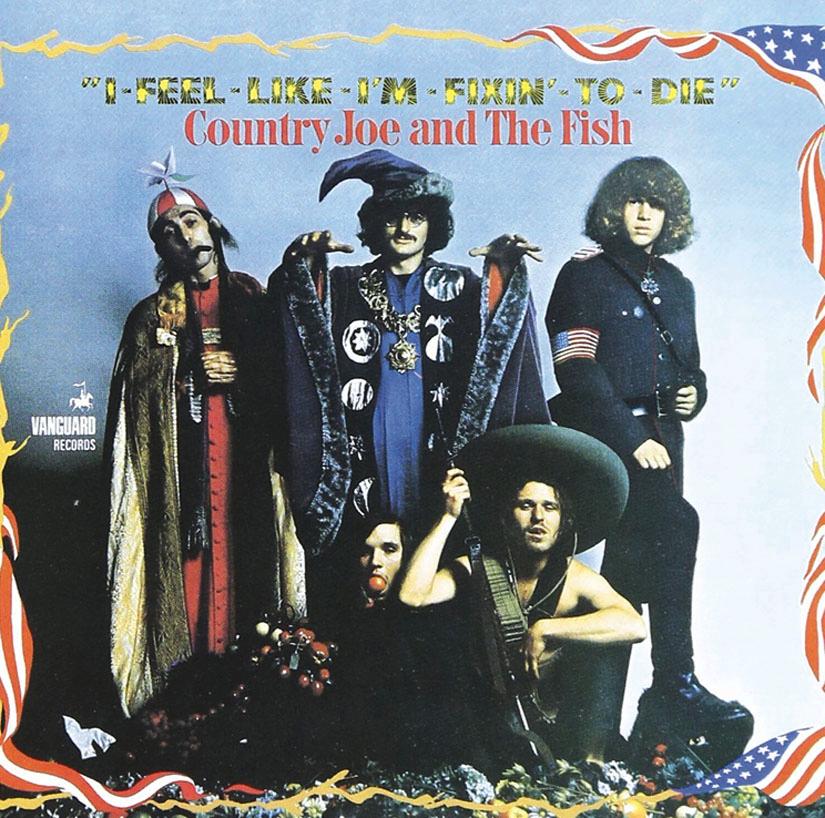

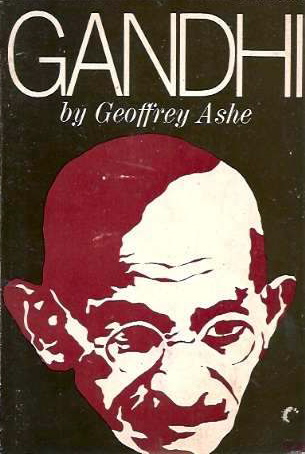

The second album Country Joe and the Fish album; Country Joe is seated front far right; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“Women coming home from the Vietnam War never were the same after their wartime experiences. They were shoved into a horrific, unbelievable experience. That’s what I wrote about in the song: ‘A vision of the wounded screams inside her brain, and the girl next door will never be the same.’” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: You first sang “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” on the streets of Berkeley during the Vietnam War in 1965. Fifty years later, you sang it at an anti-nuclear protest at Livermore Laboratory on the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Could you have imagined in 1965 that your song would still have so much meaning today?

Country Joe McDonald: Actually, I find the concept of 50 years incomprehensible. But it’s indisputable because I have children and some of those children have children and I know that the math is right. And I just finished an album and the title of it is 50 because it’s 50 years since the first album. It’s called Goodbye Blues. I didn’t die, so there you are. I’m still alive and I’m still doing something. Filling a need helps a lot, and it keeps me sane.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

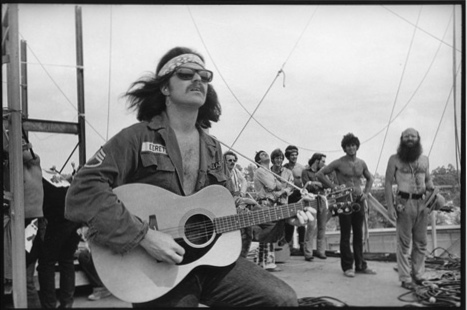

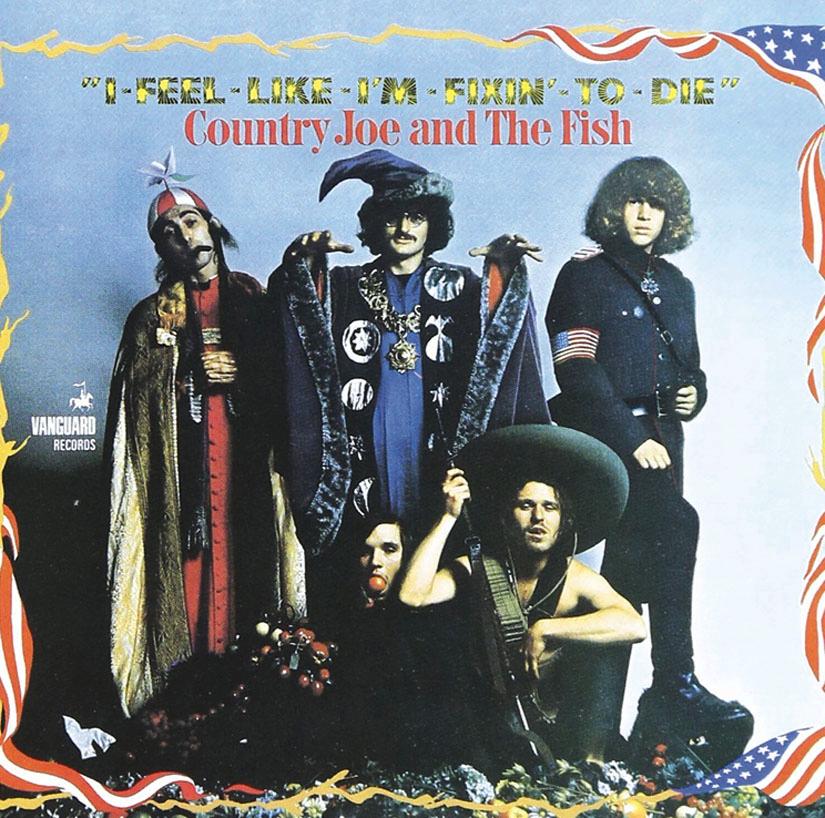

Country Joe McDonald sings “Fixin’ to Die Rag” for 300,000 people at Woodstock; photo by Jim Marshall, courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“It was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, London, and San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. It was a wonderful thing to happen. And I’m still a hippie: peace and love!” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: During the Vietnam War, and while caring for the victims of PTSD and Agent Orange in the years after the war, Lynda Van Devanter and other Vietnam combat nurses helped many veterans to survive. Your song about Van Devanter says that the combat nurse is everybody’s savior but her own. Then it asks, “Who will save her now?”

Country Joe McDonald: Yes, who will save her now?

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Country Joe McDonald sings anti-war songs; Livermore Lab, Hiroshima Day, August 6, 2015; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Country Joe McDonald composed one of the most acclaimed peace anthems of the Vietnam era, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” a rebellious and uproarious blast against the war machine. The song’s anti-war message seems more timely than ever, with its savagely satirical attack on the arms merchants, the military and the White House. “Fixin’ to Die Rag” condemns the architects of war and the military-industrial complex in bitterly sarcastic terms.

Come on Wall Street, don’t move slow

Why man, this is war au-go-go!

There’s plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade.

Recently, a major new book by Craig Werner and Doug Bradley, We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War, [Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015] ranked hundreds of Vietnam-era songs and listed “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” by Country Joe and the Fish as one of the two most important songs named by Vietnam veterans, right after “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” by the Animals. “The soldiers got it,” write co-authors Werner and Bradley about Country Joe’s song. Michael Rodriguez, an infantryman with the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, said: “Bitter, sarcastic, angry at a government some of us felt we didn’t understand — ‘Fixin’ to Die Rag’ became the battle standard for grunts in the bush.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Fred J. Blum

Logo Shanti Sena World Peace Network; courtesy mettacenter.org

Editor’s Preface: The Peace Brigade was organized in 1981 by Narayan Desai and others in London, as an extension of the Shanti Sena, or nonviolent peace force, which Vinoba Bhave had founded in India in the 1950s. Bhave had, of course, taken his name and concept from Gandhi and more specifically from Gandhi’s Constructive Programme. This previously unpublished article makes clear that activists in the U.S. nonviolence and peace movements were already thinking of forming their own chapters as early as 1961, the date on the manuscript. The Brigade still continues in many countries under various names such as the World Peace Brigade, Peace Brigades International, Muslim Peacemaker Teams, etc.. The article is another in our series from the IISG archive in Amsterdam. For further information and references please consult the notes at the end of the article. JG

What is nonviolence? When I thought about how I wanted to start this discussion I felt a need to give some initial broad definition. The first that came to my mind was “to refuse to use violence and to substitute for it other means.” As soon as I had written it down, I felt that the term “to use violence” was very limiting, and expressed a mode of thinking so prevalent today that none of us could easily escape from it, namely a thinking in instrumental terms: of using techniques, of making “things” an instrument for our purpose, for controlling our environment, etc.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

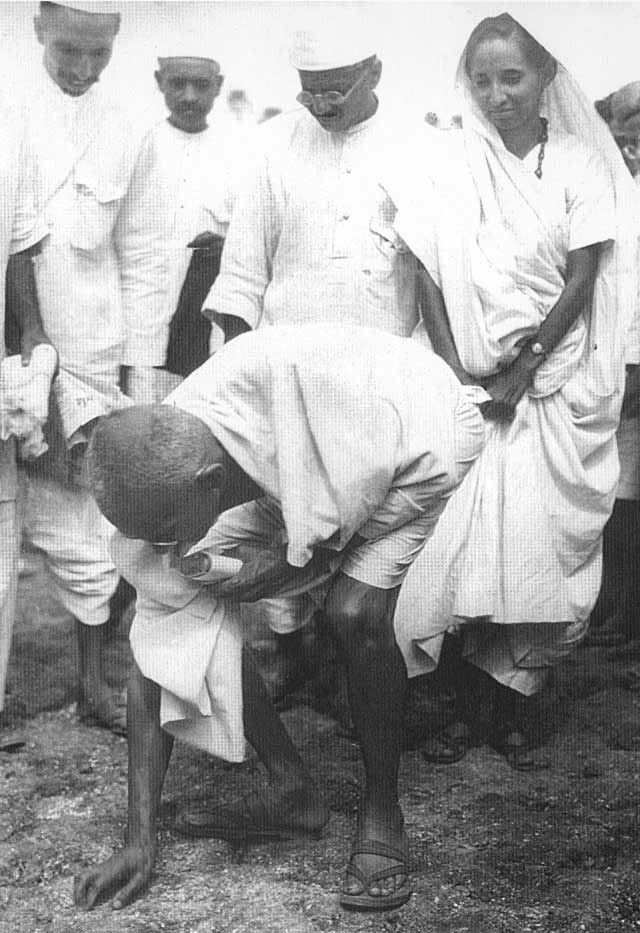

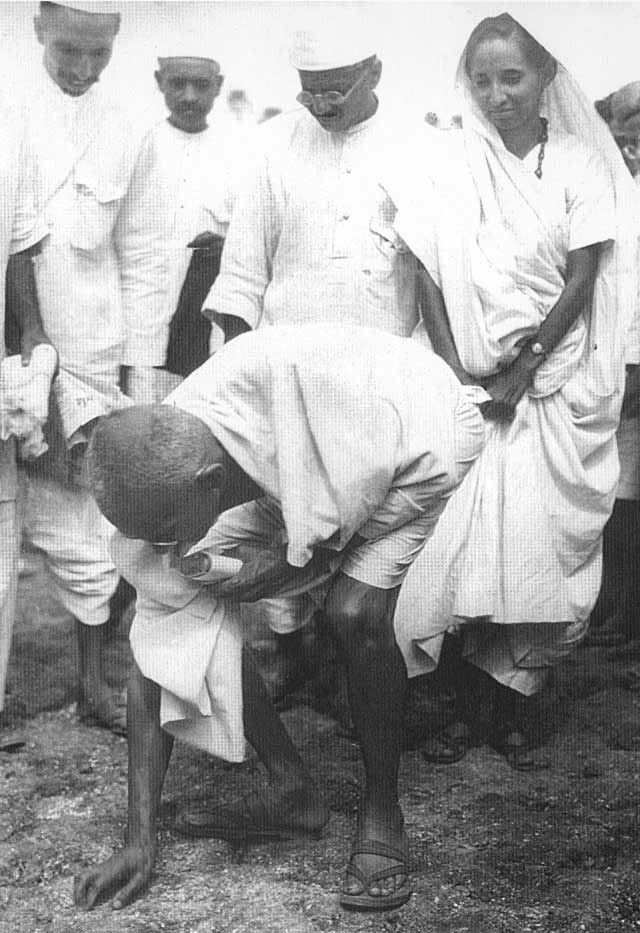

Gandhi gathers salt and breaks law; courtesy Wikipedia.com

Why Symbolism of Salt to Understand a Trouble Dissolver?

Alchemy is a kind of learning, a repository of old wisdom. It includes observations about elements, experiments with materials and aspects of the universe, as well as studies about processes and psyches. The imagination of curious souls and observers of life, active over the centuries, has experimented and found meanings in chemical and psychic interactions and transformations.

Despite modern science’s new technologies and ways of learning about the universe at various levels—micro, macro, meso—there are still valuable lessons to be learned from the ideas gathered under the term “alchemy” over the centuries. Shakespeare and other great poets are still interesting 500 years later—his grasp of human nature, his use of metaphorical language, and his observations on experience are still valuable, and this is true also for the metaphors found in alchemy.

James Hillman’s Alchemical Psychology is a brilliant contribution to understanding the richness of alchemy. In this book he garners and examines some valuable insights from the explorations of alchemy, and relates them to the processes of the human psyche. Many of the ideas in this paper are derived from Hillman’s inspiring work. I quote some points directly, others I paraphrase and elaborate on, extending them with my own examples and explicating and exploring their implications. Relating these ideas to Gandhi’s work is my idea, not Hillman’s. (1)

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

Logo Sri Lanka sarvodaya; courtesy lightmillennium.org

In March 1974, following a student demonstration in Patna against the Bihar Government and Assembly that resulted in widespread arson and looting and several deaths, Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) the leader of the Socialist Party and former Gandhi supporter, accepted an invitation from the student leaders to give guidance and direction to their movement. As he was to declare in a speech to these students, ‘After 27 years of freedom, people of this country are wracked by hunger, rising prices, corruption… oppressed by every kind of injustice… it is a Total Revolution and we want nothing less!’

His immediate purpose was to ensure that the developing agitation would be peaceful and nonviolent but, in accepting the invitation, he set in motion a train of events which included not merely splitting the Sarvodaya movement of which he was the most prominent leader after Vinoba Bhave but also, and more importantly, polarising all the major political parties and forces in India. Fifteen months later, this polarisation led to a head-on confrontation between the Opposition parties and the Central Congress Government (supported by the Communist Party of India), the outcome of which was the declaration of a state of emergency on 26th June 1975.

Read the rest of this article »

by Chaiwat Satha-Anand

Book jacket art courtesy usip.org

From 1982 to 1984, Muslims from two villages in Ta Chana district, Surat Thani, in southern Thailand had been killing one another in vengeance; seven people had died. Then on January 7, 1985, which happened to be a Maulid day (to celebrate Prophet Muhammad’s birthday), all parties came together and settled the bloody feud. Haji Fan, the father of the latest victim, stood up with the Holy Qur’an above his head and vowed to end the killings. With tears in his eyes and for the sake of peace in both communities, he publicly forgave the murderer who had assassinated his son. Once again, stories and sayings of the Prophet had been used to induce concerned parties to resolve violent conflict peacefully. (1) Examples such as this abound in Islam. Their existence opens up possibilities of confidently discussing the notion of nonviolence in Islam. They promise an exciting adventure into the unusual process of exploring the relationship between Islam and nonviolence.

This chapter is an attempt to suggest that Islam already possesses the whole catalogue of qualities necessary for the conduct of successful nonviolent actions. An incident that occurred in Pattani, Southern Thailand, in 1975 is used as an illustration. Finally, several theses are suggested as guidelines for both the theory and practice of Islam and the different varieties of nonviolence, including nonviolent struggle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Acharya K.K. Chandy

Edward Hicks, “The Peaceable Kingdom”; courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.; nga.gov

Editor’s Preface: In the writings about Gandhi’s constructive programme, there are rarely any attempts made to compare it with historical precedents. Acharya Chandy has had the insight that William Penn’s Peaceable Kingdom of Pennsylvania is an apt precursor of a Gandhian community. This previously unpublished article continues our research project at the International Institute for Social History (IISG) in Amsterdam. Please consult that category for other articles, and the project’s statement of purpose. Please also see the notes at the end for acknowledgments, biographical details, and especially a note on the condition of the text. JG

In a context where the survival of the species through nuclear war or environmental degradation has become a main anxiety of the day, ignoring the warnings given by Christ and Gandhi would be to our peril as individuals and nations. Gandhi said, “In every state in the world today, violence, even if it were for so called defensive purposes only, enjoys a status which is in conflict with the better elements of life. The organisation of the best in society should be (our) aim, and this could be done only if we succeed in demolishing the status which has been given to militarism.” (Harijan, Augustus 24,1947) Uncompromising nonviolence, Gandhi said, is adequate to meet any situation – personal, social, political, economic, national and international. As Christ said, “Put up your sword, all who take the sword die by the sword … Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good.” (Matt. 26:52)

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

Anarcho-pacifist logo courtesy peaceofmindnews.com

The development of Christian Anarchism presaged the increasing convergence (but not complete merging) of pacifism and anarchism in the 20th century. The outcome is the school of thought and action (one of its tenets is developing thought through action) known as ‘pacifist anarchism’, ‘anarcho-pacifism’ and ‘nonviolent anarchism’. Experience of two world wars encouraged the convergence. But, undoubtedly, the most important single event to do so (although the response of both pacifists and anarchists to it was curiously delayed) was the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Ending as it did five years of ‘total war’, it symbolised dramatically the nature of the modern Moloch that man had erected in the shape of the state. In the campaign against nuclear weapons in the 1950s and early 1960s, more particularly in the radical wings of it, such as the Committee of 100 in Britain, pacifists and anarchists educated each other.

Read the rest of this article »