by John Dear

Poster art courtesy paceebene.org

It was early 1968. Since the previous spring Martin Luther King, Jr. had been pursuing a course that for many was unthinkable. He had deliberately connected the dots between the movement for civil rights and the struggle to end the war in Vietnam, and had paid the price. He was roundly criticized by the Johnson administration and the media, as well as by people in his own movement. From the right he was attacked for having the gall to question US foreign policy. From the left he was lambasted for losing focus and not keeping his eyes on the prize.

He even got it from a childhood friend who stopped by the house one afternoon to vent. “Why are you speaking out against the Vietnam War?” he carped. King put aside his customary oratory. “When I speak about nonviolence,” he patiently explained, “I mean nonviolent all the way.”

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

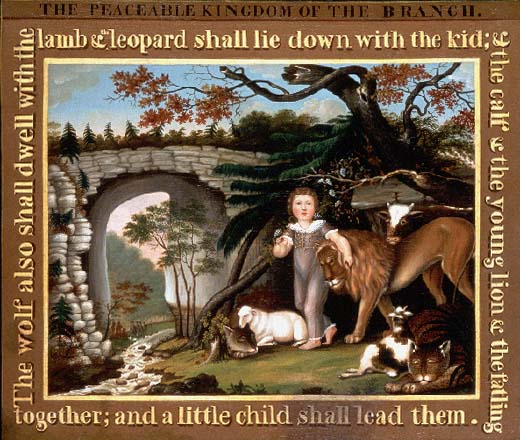

Edward Hicks, “The Peaceable Kingdom: The Leopard and the Kid”, courtesy wikimedia.org

When the 9/11 terrorist attack happened, I recalled an observation which Martin Luther King, Jr. had made when visiting singer-actor-activist Harry Belafonte in 1968: “I’ve come upon something that disturbs me deeply,” he said. “We have fought hard and long for integration, as I believe we should have, and I know that we will win. But I’ve come to believe we’re integrating into a burning house.” (italics added)

When Belafonte asked Dr. King to explain further, he said “I’m afraid that America may be losing what moral vision she may have had. And I’m afraid that even as we integrate, we are walking into a place that does not understand that this nation needs to be deeply concerned with the plight of the poor and disenfranchised. Until we commit ourselves to ensuring that the underclass is given justice and opportunity, we will continue to perpetuate the anger and violence that tears at the soul of this nation.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Arvind Sharma

Gandhi poster courtesy rishikajain.com

Truth and nonviolence are generally considered to be the two key ingredients of Gandhian thought. It is possible to pursue one without the other, possible, for example, to pursue truth without being nonviolent. Nations go to war believing truth is on their side, or that they are on the side of truth. The more sensitive among those who believe truth is on their side insist not that there should be no war but that it should be a just war. The most sensitive, however, and pacifists are among these, avoid violence altogether. But it could be argued that in doing so they have gone too far and have abandoned truth, and even justice. Although he was opposed to war, Gandhi argued that the two parties engaging in it may not stand on the same plane: the cause of one side could be more just than the other, so that even a nonviolent person might wish to extend his or her moral support to one side rather than to the other.

Just as it is possible to pursue truth without being nonviolent, it is also possible to pursue nonviolence without pursuing truth. In fact, it could be proposed that a disjunction between the two runs the risk of cowardice being mistaken for, or masquerading as, nonviolence. The point becomes clear if we take the world “truth” to denote the “right” thing to do in a morally charged situation. Gandhi was fond of quoting the following statement from Confucius: “To know what is right and not to do it is cowardice.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Tom Gibian

Sandy Spring School, 2nd Grade Art Work; courtesy grover.ssfs.org/~ksantori/art/2nd_grade.htm

One of the underlying principles of Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence is our capacity for interconnectedness, or as Gandhi was to state it, “the interconnectedness of all beings.” Interconnectedness, or connecting, is also very much at the heart of Quaker concerns.

I remember being in third grade and having to line up and pair off with a classmate to walk down the hallway to some destination beyond our classroom. At Sherwood elementary school, there might have been 29 or 30 nine-year-olds and one teacher. On the day I’m recalling, I was paired off with a kid named Sammy. I was new at Sherwood and someone warned me that Sammy had sweaty palms. As we headed down the hallway, he took my hand. His hand was sweaty, but it didn’t matter. We held hands without embarrassment. We were not self-conscious. We were little, at least relative to the world we were living in, and it could not have been more natural to reach out, to partner, to connect. Later, Sam would be one of the first friends of mine to get a high-performance muscle car in high school. That is a different story!

Read the rest of this article »

by Pope Francis

Giotto, “St. Francis Preaching to the Birds”; courtesy jssincivita.com.

Editor’s Preface: The following is the official Papal message for the 50th World Day of Peace, 1 January 2017. It is, however, the first such ever devoted exclusively to nonviolence, in the tradition of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. JG

1. At the beginning of this New Year, I offer heartfelt wishes of peace to the world’s peoples and nations, to heads of state and government, and to religious, civic and community leaders. I wish peace to every man, woman and child, and I pray that the image and likeness of God in each person will enable us to acknowledge one another as sacred gifts endowed with immense dignity. Especially in situations of conflict, let us respect this, our “deepest dignity”, (1) and make active nonviolence our way of life.

Read the rest of this article »

by Joseph Geraci

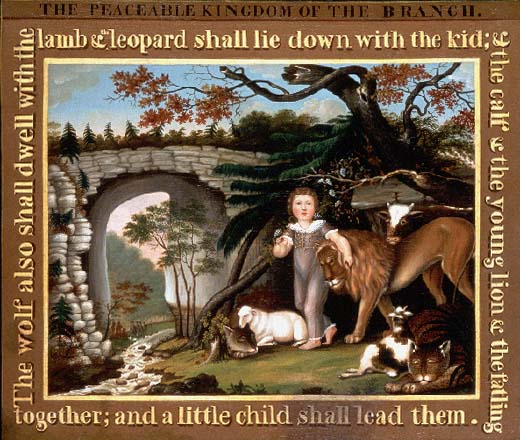

Edward Hicks painting, c. 1823, from the Peaceable Kingdom series; courtesy Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

Peace has been for centuries a universal greeting and sign. We may recall that the World War II military victory V-sign was transformed in the 1960s into a peace symbol; signs of the times. Peace was always more than a simple hello; it was a bestowal of peace on someone, a blessing. In the Middle East, for example, that area of the world so riven by violence, it is perhaps not so strange an irony that a common greeting is (in Hebrew) shalom aleikhem (Peace be with you), and the reply aleikhem shalom (Peace also be with you). In Arabic it is as-sal alaykum (Peace be with you), common to Muslims in Turkey, Indonesia, Central Asia, Iran, India, et al. The response is as-salamu alaykum, and can also be translated as “Peace also be with you”.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

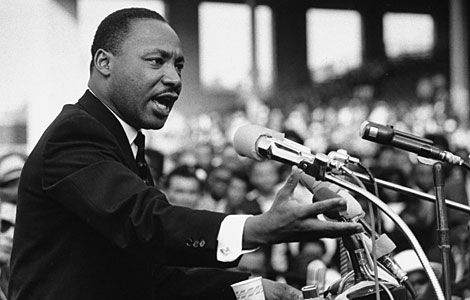

Martin Luther King, at Southern Christian Leadership Conference; courtesy vinaylal.wordpress.com

Whatever the difficulties that Martin Luther King encountered in his relentless struggle to secure equality and justice for black people, and whatever the temptations that were thrown in his way that might have led him to abandon the path that he had chosen to lead his people to the “promised land”, it is remarkable that King’s principled commitment to nonviolence never wavered through the long years of the struggle. “From the very beginning”, he told an audience in 1957, “there was a philosophy undergirding the Montgomery boycott, the philosophy of nonviolent resistance.” His own “pilgrimage to nonviolence” commenced, King wrote in Stride Toward Freedom (1958), with the realization that “the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Michael Sawyer

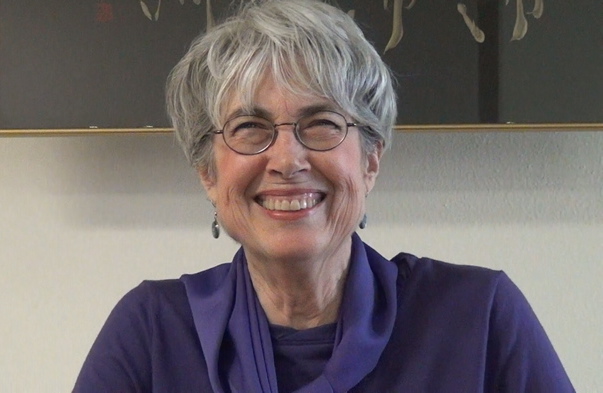

Photograph of Suzanne, 2015; courtesy Jan-Paul Vroom

We mourn the loss of our Natural World editor Suzanne Duarte, who died suddenly of natural causes on December 5, 2015 at her home in Boulder, Colorado.

Originally from California, Suzanne lived for most of her life in the western part of the country where she first came to know and love the wild places of the Earth – the Redwood Forests of northern California, Yosemite National Park, the Colorado Rockies and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of southern Colorado. They were for her the true mentors teaching us about our interconnectedness with nature, which she later recognized in the deep ecology theory of Arne Naess.

Read the rest of this article »

by John Dear

Poster art courtesy azquotes.com

Editor’s Preface: Pope Francis is the first Pope to address the U. S. Congress, and his speech is already being heralded for its stand against poverty, the death penalty and other humanitarian and spiritual concerns central to his papacy. The full speech can be read at this link. Francis also singled out four persons for praise, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Merton, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Dorothy Day, most notably the last three, major figures in the nonviolence movement. Please also see the editor’s note at the end. JG

“Hope and healing, peace and justice!” That’s what Pope Francis called us to this morning as he addressed Congress [24 September 2015]. “Summon the courage and the intelligence to resolve today’s many geopolitical and economic crises,” he said. “Our efforts must aim at restoring hope, righting wrongs, maintaining commitments, and thus promoting the well-being of individuals and of peoples. We must move forward together, as one, in a renewed spirit of fraternity and solidarity, cooperating generously for the common good.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

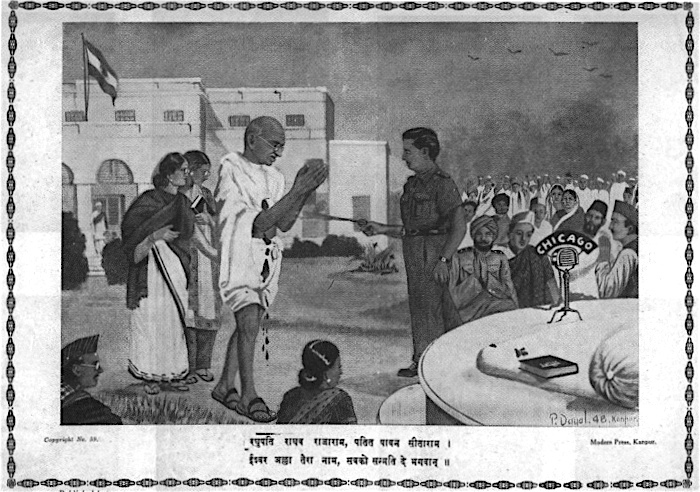

Popular Hindi press representation of Gandhi’s assassination; courtesy Vinay Lal collection

As India marked the 60th anniversary [2008] of Gandhi’s death, the tired old question of Gandhi’s “relevance” was rehearsed in the press. Once past the common rituals, we heard that the spiral of violence in which much of the world seems to be caught demonstrates Gandhi’s continuing relevance. Barack Obama’s ascendancy to the Presidency of the United States furnishes one of the latest iterations of the globalizing tendencies of the Gandhian narrative. Unlike his predecessor, who flaunted his disdain for reading, Obama is said to have a passion for books; and Gandhi’s autobiography has been described as occupying a prominent place in the reading that has shaped the country’s first African American President. Obama gravitated from “Change We Can Believe In” to “Change We Need”, but in either case the slogan is reminiscent of the saying to which Gandhi’s name is firmly, indeed irrevocably, attached: “We Must Become the Change We Want To See In the World.” Obama’s Nobel Prize Lecture twice invoked Gandhi, if only to rehearse some familiar clichés – among them, the argument, which has seldom been scrutinized, so infallible it seems, that Gandhian nonviolence only succeeded because his foes were the gentlemanly English rather than Nazi brutes or Stalinist thugs.

Read the rest of this article »