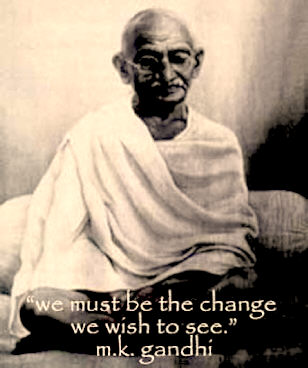

The Gandhi-Reynolds Correspondence in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection: Letters to and about Reginald Reynolds from Mahatma Gandhi, 1929-1946

by Barbara E. Addison

Editor’s Preface: We previously posted Reynolds’ article, “The Practical Application of Nonviolence,” as part of our War Resisters’ International project, found at this link. Both that article and this are additions to our ongoing series on Gandhi’s influence on pacifist and nonviolent movements in Europe and the U.S. Please consult the note at the end of the article for further information about the author. JG

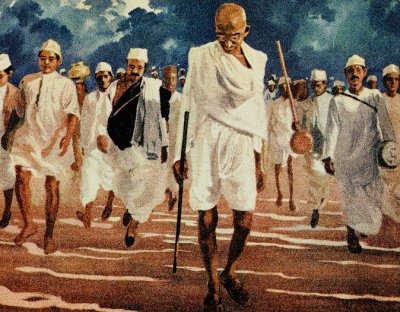

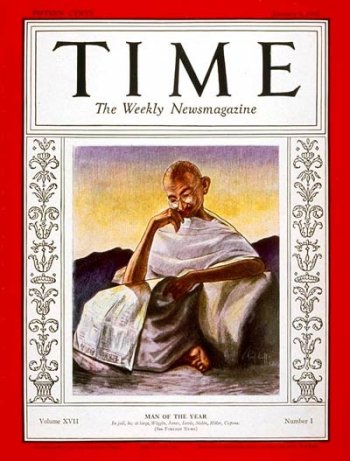

“Gandhi: Man of the Year”; Time, Jan. 5, 1931; courtesy www.kamat.com

Reginald Reynolds, a young British Quaker, corresponded with Mohandas K. Gandhi during one of the most crucial periods in Gandhi’s life and in modern Indian history: the Salt March (Salt Satyagraha) and the beginning of the 1930 Indian civil disobedience campaign against the British Raj. Reynolds was a resident in Gandhi’s ashram (spiritual retreat) at Sabarmati from 1929 to 1930. In March 1930, Gandhi appointed him to deliver a lengthy statement (generally known as “Gandhi’s Ultimatum”) to the British viceroy explaining the reasons for Gandhi’s revolt against British authority. The Gandhi-Reynolds correspondence, written primarily between 1929 and 1932, reveals Gandhi as an indefatigable political strategist, spiritual leader, and warm, attentive friend.

In 1931, Reynolds sold three of his Gandhi letters to Charles F. Jenkins, a prominent Philadelphia businessman and manuscript collector. He was parting with the correspondence in order to raise funds for his British-based organization, “The Friends of India.” He told Jenkins: “I find myself able to help them by surrendering some of my most valued possessions,” adding that he had many other letters, but had selected these as the ones with which he felt he could best part. “The rest are far too personal and precious to part with at all, and a fortune would not purchase them!” (1) The letters apparently were left to the Swarthmore College Peace Collection in Jenkins’s will, and were added to the collection in 1952. Reynolds himself donated sixteen of his “personal and precious” letters to the Peace Collection some time between 1952 and his death in 1958. Barbara Addison’s article, including scans of all the original documents, may be accessed at this link, “Gandhi Letters in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection.” (2)