by Vinay Lal

Cover art courtesy Vinay Lal

The enterprise of making a nation is fraught with violence. People have to be not merely cajoled but browbeaten into submission to become proper subjects of a proper nation-state. Overt violence may not always play the primary role in producing the homogenous subject, but social phenomena such as schooling cannot be viewed merely as innocuous enterprises designed to ‘educate’ subjects of the state. One of the most widely cited works to have put forward this argument with elegance and scholarly rigor is Eugen Weber’s Peasants into Frenchmen, where one learns, with much surprise, that even in the Third Republic, “French was a foreign language for half the citizens.” The making of France entailed not only the modernization of the rural countryside but creating, often with violence, proper subjects of a proper nation-state. The making of the United States offers another narrative of the role of violence in the production of the nation-state, with the extermination of Native Americans long before and much after the ‘Revolutionary War’ constituting the most vital link in the long chain of violence that marked the emergence of the United States.

Postcolonial thought, attentive as always to the politics of nation-making and nationalism’s complicity with colonialism, bestowed considerable attention on the various phenomena that can be accumulated under the rubric of violence; however, it had almost no time to spare for a pragmatic, ethical, or even philosophical consideration of nonviolence. The violence of the nation-state may have always been present to the mind of postcolonial theorists, but generally this was reduced to the violence of the colonizer. One thinks, of course, of Fanon, Cesaire, Memmi, and many others in this respect. In those works that have underscored the complicity of nationalist and imperialist thought, a principal motif in the work (say) of Ranajit Guha, the violence of indigenous elites also came under critical scrutiny. (See, for example, Guha’s Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1999) It is characteristic of most social thought in the West that it has been riveted on violence – here, postcolonial thought barely diverged from orthodox social science, mainstream social thought, or the general drift of humanist thinking. Nonviolence is barely present in intellectual discussions. We see here history’s continuing enchantment with ‘events’; nonviolence creates little or no noise, it merely is, it only fills the space in the background.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Book cover art courtesy navajivantrust.org

A celibate for the greater part of his life, Mohandas Gandhi continues to attract nearly unrivalled attention – often for the sex that did not take place. Even his friends and admirers, who revered him for bringing ethics to the political life, or for never demanding of others what he did not first demand of himself, were quite certain that Gandhi was unable to comprehend that a woman and a man might enjoy a perfectly healthy sexual relationship with each other. Nehru, seldom critical of the personal life of his political mentor, was convinced that Gandhi harboured an “unnatural” suspicion of the sexual life; and he deplored, as did many others, Gandhi’s strongly held view that sexual intercourse, other than for purposes of procreation, had no place in civilised life – not even among married couples. The Marxists have long subscribed to the view that Gandhi was a “romantic”, a hopeless idealist and even hypocrite; to this a chorus of voices added the thought that Gandhi was an insufferable “puritan”.

Gandhi’s discomfort with the sexual life, according to one widely accepted strand of thought, commenced when his father passed away shortly after his marriage to Kasturba. Though the young Gandhi liked to nurse his ailing father, one evening he was unable to contain his urge to share a night of ribaldry with his young wife. He had just withdrawn to the bedroom when a knock on the door announced that his father had passed away. Gandhi was, it has been argued, never able to forgive himself his transgression, and became determined to master his sexual drive. A more complex narrative links his renunciation of sex to his firm conviction, first developed during the heat of a campaign of nonviolent resistance to oppression in South Africa, that it compromised his ability to be a perfect satyagrahi. Many commentators have pointed to his failure to consult with Kasturba before he took a vow of celibacy at the age of 37 as a sign of his cruelty and tendency to be self-serving.

Read the rest of this article »

by Thakurdas Bang

Peace News poster; courtesy peacenews.info

UNESCO’s famous opening sentence declares, “Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defence of peace must be constructed.” What shall be the nature of such a society or community where the defence of peace is firmly laid? Surely such a community would be homogenous and interpersonal. As Gandhi said, “We can realise truth and nonviolence only in the simplicity of village life . . . Man should rest content with what are his real needs . . . Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s need but not for every man’s greed. No one will be idle and no one will wallow in luxury. It will be a community in whose management all members freely and fearlessly participate. It must have a unity and a sense of purpose. Such a community will surely be based on social and economic equality.”

If we examine the condition of the recently liberated Asian and African nations and especially of India on the basis of these criteria, what do we find? Although political liberation has been secured, political power is still highly centralised and has not filtered down to towns and villages. The people still look to the government for everything. Everybody talks of rights, and few lay stress on duties. The blind copying of the Western democratic structure with its paraphernalia of political parties and decisions by majority has transformed every village and town into a warring camp. Villagers do not meet to discuss their problems and participative democracy is still a distant reality. Economic equality is a long way off and people are in acute poverty: large numbers of the unemployed live side by side with the rich steeped in their luxury. Chinese Communism is knocking at the door of India, yet the Indian rich evade taxation, and any legislation that might set limits on land. Nobody lays a stress on duty. Education in self-reliance and mutual cooperation is the crying need of the hour. How to bring about this psychological change leading to the corresponding institutional change?

Read the rest of this article »

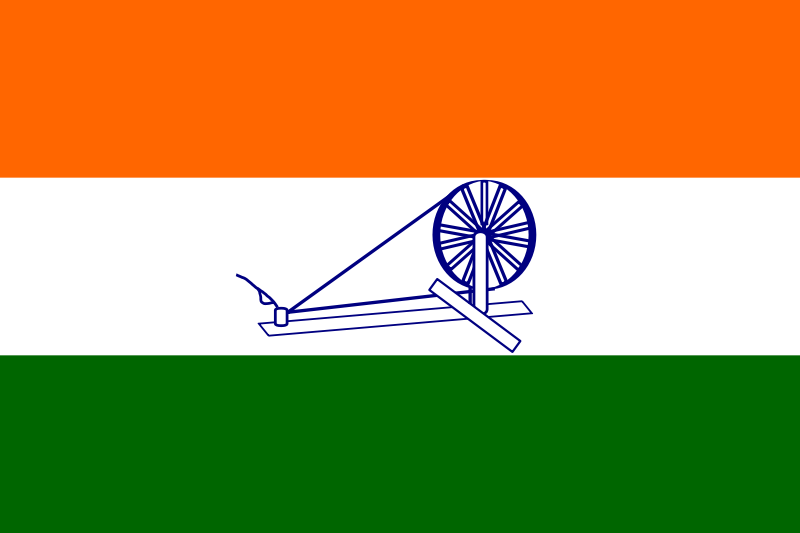

by Devi Prasad

Gandhi’s “Swaraj Flag”, 1931; courtesy en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flag_of_India

Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of freedom is illustrated by that statement in which he clearly said that India would truly be free when freedom reaches the door of the most dilapidated hut in the poorest village of the country. He said that when the British leave the country, swaraj (freedom) will of course reach New Delhi, but until it goes to every hut, and every village feels freedom (swaraj) in his own life, it will not be of much meaning. What he meant was that until the common man of India lives a life of dignity and fearlessness, India will not achieve the freedom of his concept. He once stated: ‘One sometimes hears it said: “Let us get the Government of India in our own hands and everything will be all right.” There could not be greater superstition than this. No nation has thus gained its independence. The splendour of the spring is reflected in every tree, the whole earth is then filled with the freshness of youth. Similarly, when the swaraj spirit has really permeated society, a stranger suddenly come upon us will observe energy in every walk of life . . . Swaraj for me means freedom for the meanest of our countrymen. I am not interested in freeing India merely from the English yoke. I am bent upon freeing India from any yoke whatsoever.’ At another occasion he said: ‘Self-government means continuous effort to be independent of government control whether it is foreign government or whether it is national.’

Read the rest of this article »

by Charles Petrasch

Poster of Marx, Gandhi, and Hahnemann, the founder of homeopathy; courtesy arvindarora40.blogspot.nl

Editor’s Preface: Charles Petrasch was a French journalist working for the French newspaper Le Monde, and in the 1930s was their London correspondent. This interview was conducted in English on 29 October 1931, while Gandhi was in London to attend the Round Table Conference, being held by the British government to discuss constitutional reforms in India. Gandhi wanted self-rule or swaraj. To put pressure on the British government he had organized in India a boycott of British goods, especially cotton and cloth products from the northern English Lancashire mill towns. Gandhi’s sympathies were with labor, and while in England he visited the Lancashire mills to express solidarity, and was warmly received by the unions and workers. It was in this context that the interview took place. Petrasch wrote at the time: “My Indian friends and I had drawn up a list of questions which we wished to put to Gandhi before his departure from London, and we wrote down his replies as the interview went on.” Petrasch’s Indian friends were Marxists, and the interview appeared in Labour Monthly, a Marxist magazine founded and edited by Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) theoretician Rajani Palme Dutt (1896-1974). There was an ongoing dialogue between Gandhi and the Indian and European Marxists, some of it rancorous, as might be surmised by the asides in this interview. We have posted several other articles about Gandhi and Marxism, accessible through our search function. See the note at the end for further textual information regarding publications and dates. JG

Charles Petrasch: In your opinion, what is the method by which the Indian princes, landowners, industrialists and bankers acquire their wealth?

Mohandas K. Gandhi: At present by exploiting the masses.

Read the rest of this article »

by Krishna Kumar

Gandhi poster courtesy izquotes.com

Rejection of the colonial education system, which the British administration had established in the early nineteenth century in India, was an important feature of the intellectual ferment generated by the struggle for freedom. Many eminent Indians, political leaders, social reformers and writers voiced this rejection. But no one rejected colonial education as sharply and as completely as Gandhi did, nor did anyone else put forward an alternative as radical as the one he proposed. Gandhi’s critique of colonial education was part of his overall critique of Western civilisation. Colonisation, including its educational agenda, was to Gandhi a negation of truth and nonviolence, the two values he held uppermost. The fact that Westerners had spent ‘all their energy, industry, and enterprise in plundering and destroying other races’ was evidence enough for Gandhi that Western civilisation was in a ‘sorry mess’. (1) Therefore, he thought, it could not possibly be a symbol of ‘progress’, or something worth imitating or transplanting in India.

Read the rest of this article »

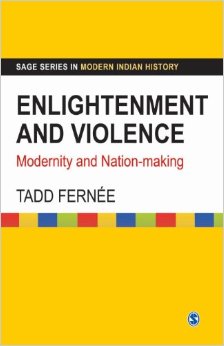

by Tadd Graham Fernée

Cover art courtesy sagepub.in

The sea changes in 20th century experience provide the ground for dismantling the often tacit colonial paradigm which erased non-Western viewpoints, and for incorporating the wider human experiences of modernity, development, progress, scientific achievement, secularism, the nation, justice, ethics and aesthetics. A case is made in my book, Enlightenment and Violence: Modernity and Nation-Making, for an Enlightenment ideal grounded in identifiable values committed to nonviolent conflict resolution, rather than a single cognitive worldview claiming a ‘new’ monopoly on ‘truth’. Modern science, in itself, yields no fixed picture of things, nor provides the comfort of a single fixed worldview. It follows that the Enlightenment heritage should shift from totalizing epistemic claims to the ethical core of Enlightenment in nonviolence. Where claims to total truth or moral certitude justify mass murder – even on grounds of modern secular ideologies – the Enlightenment has been fundamentally betrayed. From this perspective, the book is an auto-critique of the many-sided universal Enlightenment heritage. It comparatively studies nation-making patterns, experiments and revolutions in terms of the criterion of non-violence as an ideal normative value.

Read the rest of this article »

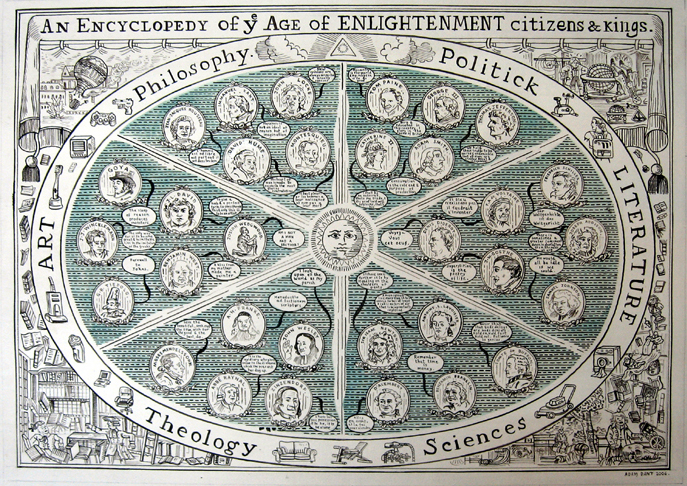

by William J. Jackson

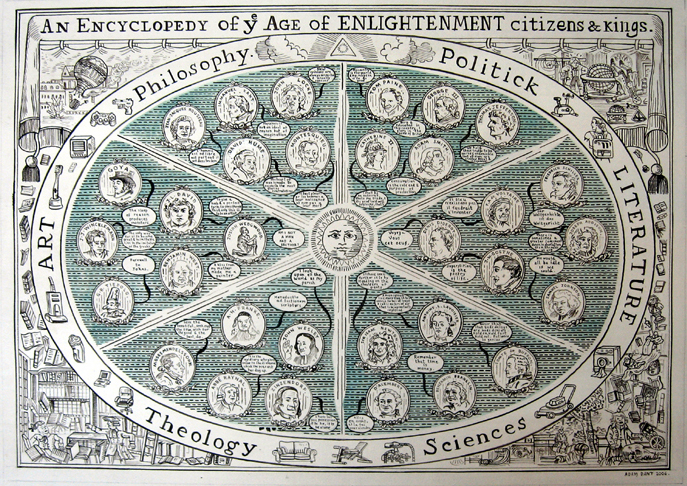

19th century print of the Enlightenment, courtesy adambaumgoldgallery.com

Tadd Graham Fernée’s new book, Enlightenment and Violence: Modernity and Nation-Making, causes readers to consider some timely issues. I will begin by mentioning some of the issues it has caused me to mull over and explore, questions the book raises both directly and indirectly.

Chronologically, the European Enlightenement ran from 1650-1800. It was a period of remarkable advances in rationality, science and technology, and also a time of new social theories and revolutionary acts of violence ushering in the modern age. Typical dictionary definitions describe the Enlightenment as an eighteenth century movement of philosophical thought which explored the potential of the empirical method in science, questioned authority, and developed new political theories. While many people think of the Enlightenment as dead and gone, it is possible, and reasonable, to see it in another way. It can be seen as a time of blossoming advances which are still bearing fruit, of ongoing intellectual probes and experiments still giving birth to new sets of viewpoints and refinements which are capable of being informed by non-Europeans now, long after the chronological period of the original phase of the Enlightenment has passed.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mohandas K. Gandhi

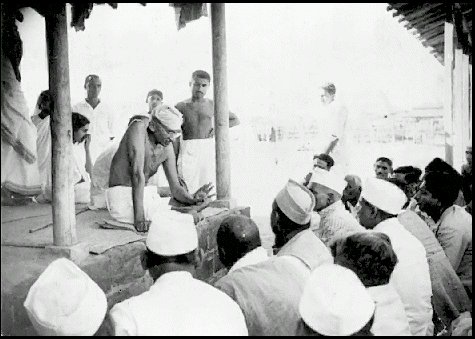

Gandhi teaching his followers; courtesy mkgandhi.org

Editor’s Preface: Gandhi highly valued education as an essential part of his nonviolence program, and insisted it be included in the daily life of the various ashrams that he founded. (1) If regular classes were held for children, adults were also asked to learn spinning, weaving, cloth making, and a host of other skills. It was not until 1909, however, that Gandhi began to systematize his thoughts, in the essay that follows. It is, in fact, Chapter 18 of one of his most important and influential works, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, presented as a series of questions and answers between the fictitious, if sometimes obtuse “Reader”, and answers by a knowing “Editor”, both of whom, needless to say are Gandhi. Hind Swaraj was written in a flurry of work between 13 and 22 November 1909 while Gandhi was on board the Kilnonan Castle sailing back from England to South Africa. Although he continued to write about education in Young India, Indian Opinion, and other of the periodicals he edited, the text that follows is recognized as his first attempt to outline the basics of a curriculum consisting of language, Indian civilization, and ethics. Please consult the notes at the end for further bibliographical information. JG

Reader: In the whole of our discussion, you have not demonstrated the necessity for education; we always complain of its absence among us. We notice a movement for compulsory education in our country. The Maharaja Gaekwar has introduced it in his territories. (2) Every eye is directed towards them. We bless the Maharaja for it. Is all this effort then of no use?

Editor: If we consider our civilization to be the highest, I have regretfully to say that much of the effort you have described is of no use. The motive of the Maharaja and other great leaders who have been working in this direction is perfectly pure. They, therefore, undoubtedly deserve great praise. But we cannot conceal from ourselves the result that is likely to flow from their effort. What is the meaning of education? It simply means knowledge of letters. It is merely an instrument, and an instrument may be well used or abused. The same instrument that may be used to cure a patient may be used to take his life, and so may knowledge of letters. We daily observe that many men abuse it and very few make good use of it; and if this is a correct statement, we have proved that more harm has been done by it than good. (3)

Read the rest of this article »

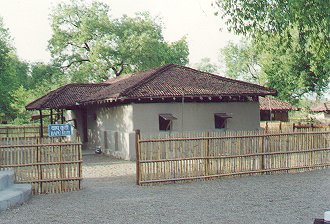

by Dr. Abhay Bang

Sevagram Ashram, c. 1960s; courtesy mkgandhi.org

As a child growing up in the 1960s I went to an amazing school. Today, I feel helpless and sad because I’m unable to offer such an education to my son, Anand. “Our childhood was so different. Things have changed beyond recognition,” old timers often moan and groan about the past. Still, my heart is heavy. You may ask what was so different about my school?

From grades four to nine I studied in a school which followed Gandhi’s Basic Education tenets (Nai Taleem), located at Sevagram ashram in Wardha, founded by Gandhi in the 1930s. Education should not be confined within the four walls of the classroom mugging up boring subjects away from Mother Nature. Gandhiji’s Nai Taleem strongly believed that children learnt best by doing socially useful work in the lap of nature. This is how children’s minds would develop and they would imbibe a variety of useful skills. To implement such a system of education, the great poet and Nobel Prize winner, Rabindranath Tagore, at the behest of Gandhiji sent two brilliant teachers to Sevagram. Mr. Aryanakam came all the way from Sri Lanka and Mrs. Asha Devi from Bengal. This duo combined Gandhi’s educational methodology with Tagore’s love for nature and the arts. My parents, followers and friends of Gandhi, were involved with this educational experiment right from the start. The school tried out many novel experiments in education. Here, I will attempt to recall some of these.

Read the rest of this article »