by Max Cooper

Cover art courtesy stevenpinker.com

Amongst the scores of letters he attended to every day, Mahatma Gandhi responded to one V.N.S. Chary, on April 9, 1926. Chary’s original letter does not survive, but we may reconstruct from the Mahatma’s response that he raised a particular existential question that has long troubled many practitioners of nonviolence: Is overcoming violence really possible? Is violence not simply an ineluctable feature of embodied existence and human nature? Questions in this spirit have a long history, having been explored by thinkers such as Heraclitus, Freud, Nietzsche, and others, who have often emphasized the essential duality of worldly existence – of the mutual necessity of opposites – for good to exist, so must evil; to know peace, perhaps we must know violence.

In his letter, Mr. Chary appears to have cited examples from the animal world: Hawks eat snakes; snakes eat lizards; lizards eat cockroaches, who themselves eat ants. This violence is simply natural, and it occurs perhaps for a greater good. If beings did not eat other beings, life on earth would not be possible. Beyond Chary’s points, we might also reflect that even our own human bodies are unavoidably violent; besides periodically crushing or inhaling insects unawares, our own white blood cells are constantly exterminating malignant bacteria; if they failed to kill these bacteria, we would die. Is violence not necessary for life, and should we not see it as unreasonable, or indeed impossible, to hope for a renunciation of violence?

Read the rest of this article »

by H. Runham Brown

Editor’s Preface: H. Runham Brown was a British anarchist and secretary of War Resisters’ International. He was appointed in 1931, soon after being released from prison, having served two years for conscientious objection. He authored books about peace and the Spanish civil war, and Hitler’s rise. This article is taken from The War Resister: Quarterly News Sheet of the War Resisters’ International, issue XXXI, Summer 1932. Please also see the archive reference information and acknowledgments at the end. JG

Few people in the West can understand why a man should go on a hunger strike. It appears to them that he is only hurting himself and they would rather hurt somebody else. We do not here ask that so strange an action should be understood, but that a fact should be taken notice of. From time to time a man in prison refuses to take food until his objective has been attained. He is forcing the issue. Such action may be wise or foolish; it depends on the man.

Read the rest of this article »

by A. Fenner Brockway

Editor’s Preface: Brockway’s short article appeared in The War Resister: Quarterly News Sheet of the War Resisters’ International, issue XXVII, Winter 1930-1931. It is another in our series tracing Gandhi’s impact on European and American individuals and movements, and is also another posting in our WRI project category, accessible at this link. Please also consult the notes at the end for biographical information about Brockway, archive reference, and acknowledgements. JG

The method of nonviolence as a positive instrument for securing freedom and justice is being employed in India on a scale never before attempted in human history. The development and results of the Nationalist struggle will be of greatest importance to the future of our movement as a practical contribution to the solution of the world’s problems.

The Indian people have adopted the method of nonviolence for two reasons. With Mr. Gandhi and his immediate followers it has been a matter of principle. Mr. Gandhi sees brute force as the instrument of tyranny and its mentality as the philosophy of tyranny; he cannot therefore adopt it as the instrument and philosophy of freedom. But with many of Mr. Gandhi’s colleagues, nonviolence has been a matter of expediency. The Indian people are unarmed; the British have guns and armoured cars and bombing aeroplanes. Under such conditions the method of force would be suicidal.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vladimir Tchertkoff

Editor’s Preface: The prominent religious figure Vladimir Tchertkoff was Tolstoy’s editor in the latter part of Tolstoy’s life. This letter, dated 9 March 1931 is taken from The War Resister: Quarterly News Sheet of the War Resisters’ International, issue XXIX, Summer 1931, and is another in our WRI project. We have also previously posted several articles by Tchertkoff, including unpublished correspondence with Gandhi and a previously unpublished Tolstoy translation. Please consult the Editor’s Note at the end for further biographical information and links. Tchertkoff’s other articles may be accessed via our WRI Project category. JG

Dear Mahatma Gandhi,

Allow me, on behalf of myself and our Moscow friends, to express our deep and heartfelt joy at your liberation from prison. We earnestly desire for you the necessary strength to continue your righteous and great work. May God help India to attain as quickly as possible that emancipation from foreign dominance that she so fervently desires. We yet more desire for you and ourselves the emancipation of everyone, not only from foreign oppression, but particularly from all servitude of man to man, even though it be within the limit of one and the same race; and especially from the last remnants of that superstition that one can [anymore] protect any righteous cause by force of arms or military preparations.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mohandas Gandhi

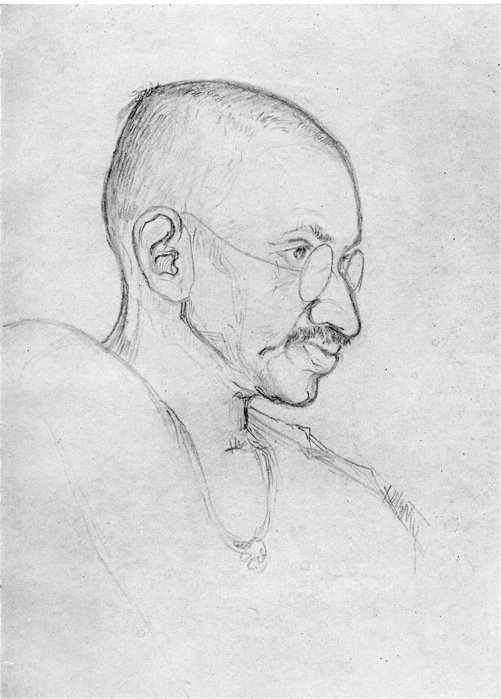

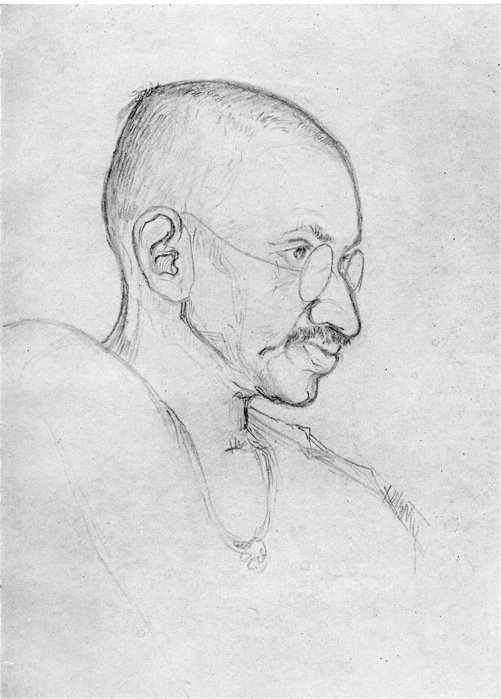

Pencil drawing of Gandhi, 1931, by Kanu Desai; courtesy Golden Vista Press

Editor’s Preface: This article, another in our WRI project, is from The War Resister: Quarterly News Sheet of the War Resisters’ International, issue XXVII, Winter 1930-1931. Pre-World War II, European pacifists were slow to come under the influence of Gandhi. They had disavowed violence in all its forms, but were not always sure that Gandhian satyagraha was an equal commitment. WRI consistently supported Indian independence and self-rule, and about this aspect of Gandhism there was no ambivalence. Please also see the archive reference information and acknowledgments at the end. JG

Here in Gujarat well tried and popular public servants have been arrested one after another, and yet the people have been perfectly nonviolent. They have refused to give way to panic, and have celebrated the arrests, by offering civil disobedience in ever-increasing numbers. This is just as it should be.

If the struggle so auspiciously begun is continued in the same spirit of nonviolence to the end, not only shall we see Purna Swaraj [complete independence] in our country before long, but we shall also have given the world an object lesson worthy of India and her glorious past.

Swaraj [self-rule] won without sacrifice cannot last long. I would therefore like our people to get ready to make the highest sacrifice they are capable of. In true sacrifice all the suffering is on one side; one is required to master the art of getting killed without killing, of gaining life by losing it. May India live up to this mantra . . .

Read the rest of this article »

by War Resisters’ International

Editor’s Preface: These two articles are from The War Resister: Quarterly News Sheet of the War Resisters’ International, issue XXVII, Winter 1930-1931. As we have noted in the preface of the Gandhi statement also posted under this date, the European peace movements were divided over the influence of Gandhian nonviolence. Even by the early 1930s some European intellectuals such as Bart de Ligt were convinced of the possibility of another world war. It is against this dramatic background that the debates about Gandhian nonviolence must be seen. Please also see the archive reference information and acknowledgments at the end, and also consult our WRI project category to access de Ligt’s and other articles on the debate with Gandhi. JG

Article One: A Message to Gandhi

The first message to reach Mahatma Gandhi from British shores after the Civil Disobedience Campaign commenced [1929-30] was from the Executive of the War Resisters’ International. It read: “(We) are watching with intense interest the progress of your campaign in India. In accordance with the principles of the W.R.I, we believe in the possibility of overthrowing imperialism by pacifist means, and we rejoice that you are relying upon the method of nonviolence. We send you our love and sympathy in the hardships and difficulties which you will undoubtedly have to face and assure you that we will do our best by propaganda in whatever circles will be open to us, to assist you in your fight for truth and justice.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

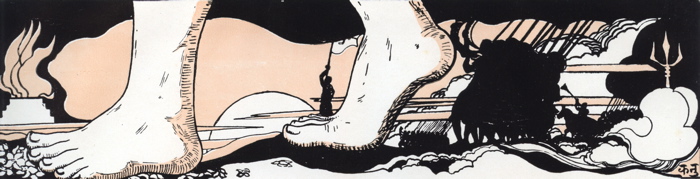

“Gandhi’s Salt March”; color woodblock print, 1931 by Kanu Desai; courtesy Golden Vista Press

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished essay is the text of a speech delivered by Geoffrey Ostergaard (1926-1990) 25 October, 1974 to the Muirhead Society, University of Birmingham (UK), and is another in our ongoing series of rediscoveries of important historical interpretations of Gandhian nonviolence. Ostergaard was one of Gandhi’s most intelligent critics, and we have posted other articles by him. Please see the notes at the end for further information about this text, biographical information about Ostergaard, links, etc. JG

Discussions of nonviolence tend, not unnaturally, to focus on the issue of the supposed merits, efficacy and justification of nonviolence when contrasted with violence. In this paper, however, I propose to pursue a different tack and I shall have little to say directly about the main issue. My object is to explicate the Gandhian concept of nonviolence and I think that this can best be done, not by contrasting nonviolence with violence but by distinguishing two kinds of nonviolence. My thesis, in short, is that nonviolence presents to the world two faces which are often confused with each other but which need to be distinguished if we are to appraise correctly Gandhi’s contribution to the subject.

Read the rest of this article »

by Alex Supron

Editor’s Preface: The University of Rhode Island Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies holds an annual Gandhi Essay Contest for all Rhode Island eighth graders (c. ages 13-14). The essay below, by eighth grader Alex Supron of St. Michael’s Country Day School in Newport, Rhode Island, won first place in the 2012-2013 competition. His essay was selected from a field of 88 entries with 21 finalists. Please see the Editor’s Note at the end for links and further information. JG

Photo of Alex Supron; courtesy web.uri.edu

“Service is not possible unless it is rooted in love and ahimsa. The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in service to others.” This was a tenet of Mahatma Gandhi, one of the greatest leaders in history. Gandhi believed that by living a life focused beyond your own personal needs you are able to better serve humanity and make the world a better place.

He was not alone in these beliefs. Many great leaders throughout history have touted the importance of serving others. Confucius said: “He who wishes to secure the good of others, has already secured his own.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was greatly inspired by Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence and belief in the importance and satisfaction of serving. He felt that if the world were to change it would take the efforts of many: “ Everybody can be great because anybody can serve.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Illustration courtesy mayapur.com

More so than any other major political figure of modern times, Mohandas Gandhi was a man of religion – though perhaps not in the most ordinary sense of the term. No political figure of the last few hundred years brought religion, or more properly the religious sensibility, into the public domain as much as Gandhi. He concluded his autobiography, first published in 1927, with the observation that those who sought to disassociate politics and religion understood the meaning of neither politics nor religion. Indeed, the most pointed inference we can draw from Gandhi’s life is the following: the only way to be religious at this juncture of human history is to engage in the political life, not politics in the debased sense of party affiliations, or the politics that one associates with being conservative or liberal, but politics in the sense of political awareness. After Gandhi, we must clearly understand, as did Arnold Toynbee and George Orwell, that the saint’s religiosity can only be tested in the slums of life.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Cover art courtesy vedicbooks.net

In a lecture given in 1993, the Indian historian Ramachandra Guha proposed to inquire whether Gandhi could be considered an “early environmentalist”. (1) Gandhi’s voluminous writings are littered with remarks on man’s exploitation of nature, and his views about the excesses of materialism and industrial civilization, of which he was a vociferous critic, can reasonably be inferred from his famous pronouncement that the earth has enough to satisfy everyone’s needs but not everyone’s greed. Still, when ‘nature’ is viewed in the conventional sense, Gandhi was rather remarkably reticent on the relationship of humans to their external environment. His name is associated with innumerable political movements of defiance against British rule as well as social reform campaigns, but it is striking that he never explicitly initiated an environmental movement, nor does the word ‘ecology’ appear in his writings. Again, though commercial forestry had commenced well before Gandhi’s time, and the depletion of Indian forests would persistently provoke peasant resistance, Gandhi himself was never associated with forest satyagrahas, however much peasants and rebels invoked his name.

Guha also observes that, “the wilderness had no attraction for Gandhi.” (2) His writings are singularly devoid of any celebration of untamed nature or rejoicing at the chance sighting of a wondrous waterfall or an imposing Himalayan peak; and indeed his autobiography remains utterly silent on his experience of the ocean, over which he took an unusually long number of journeys for an Indian of his time. In Gandhi’s innumerable trips to Indian villages and the countryside — and seldom had any Indian acquired so intimate a familiarity with the smell of the earth and the feel of the soil across a vast land — he almost never had occasion to take note of the trees, vegetation, landscape, or animals. He was by no means indifferent to animals, but he could only comprehend them in a domestic capacity. Students of Gandhi certainly are aware not only of the goat that he kept by his side and of his passionate commitment to cow-protection, but of his profound attachment to what he often described as ‘dumb creation’, indeed to all living forms.

Read the rest of this article »