by Acharya K.K. Chandy

Edward Hicks, “The Peaceable Kingdom”; courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.; nga.gov

Editor’s Preface: In the writings about Gandhi’s constructive programme, there are rarely any attempts made to compare it with historical precedents. Acharya Chandy has had the insight that William Penn’s Peaceable Kingdom of Pennsylvania is an apt precursor of a Gandhian community. This previously unpublished article continues our research project at the International Institute for Social History (IISG) in Amsterdam. Please consult that category for other articles, and the project’s statement of purpose. Please also see the notes at the end for acknowledgments, biographical details, and especially a note on the condition of the text. JG

In a context where the survival of the species through nuclear war or environmental degradation has become a main anxiety of the day, ignoring the warnings given by Christ and Gandhi would be to our peril as individuals and nations. Gandhi said, “In every state in the world today, violence, even if it were for so called defensive purposes only, enjoys a status which is in conflict with the better elements of life. The organisation of the best in society should be (our) aim, and this could be done only if we succeed in demolishing the status which has been given to militarism.” (Harijan, Augustus 24,1947) Uncompromising nonviolence, Gandhi said, is adequate to meet any situation – personal, social, political, economic, national and international. As Christ said, “Put up your sword, all who take the sword die by the sword … Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good.” (Matt. 26:52)

Read the rest of this article »

by Sita Kapadia

M. K. Gandhi and wife, Kasturba, 1902; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Mahatma Gandhi’s legacy to the world is immeasurable; his life and work have left an impact on every aspect of life in India; he has addressed many personal, social and political issues; his collected works number more than one hundred volumes. From these I have gleaned only a few thoughts about women and social change.

In 1940, reviewing his twenty-five years of work in India concerning women’s role in society, he says, “My contribution to the great problem lies in my presenting for acceptance truth and ahimsa (nonviolence) in every walk of life, whether for individuals or nations. I have hugged the hope that in this woman will be the unquestioned leader and, having thus found her place in human evolution, will shed her inferiority complex … Woman is the incarnation of ahimsa. Ahimsa means infinite love, which again means infinite capacity for suffering. And who but woman, the mother of man, shows this capacity in the largest measure? … Let her translate that love to the whole of humanity … And she will occupy her proud position by the side of man … She can become the leader in satyagraha.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Raghavan N. Iyer

Poster illustration courtesy en.wikisource.org

Most political and social thinkers have been concerned with the desirable (and even necessary) goals of a political system or with the common and competing ends that men actually desire, and then pragmatically considered the means that are available to rulers and citizens. Even those who have sought a single, general, and decisive criterion of decision-making have stated the ends and then been more concerned with the consequences of social and political acts than with consistently applying standards of intrinsic value. It has become almost a sacred dogma in our age of apathy that politics, centred on power and conflict and the quest for legitimacy and consensus, is essentially a study in expediency, a tortuous discovery of practical expedients that could reconcile contrary claims and secure a common if minimal goal or, at least, create the conditions in which different ends could be freely or collectively pursued.

Read the rest of this article »

by Anil Nauriya

When I am contradicted it arouses my attention, not my wrath.

I move towards the man who contradicts me: he is instructing me.

The cause of truth ought to be common to us both. Montaigne

The debates on Gandhi’s role as a personality and as a symbol of Indian nationalism will go on; the purpose of this article is mainly to draw attention to some points of methodology which, when overlooked, lead to erroneous and even absurd results.

First, analysis confined to comparing the positions of any individuals or organizations at a single arbitrarily chosen point in time is inadequate. Gandhi as well as his critics were continually evolving. The movement in their positions is often of more significance than their points of view at any isolated moment.

Read the rest of this article »

by Sean Chabot

Dust jacket courtesy Oxford University Press; global.oup.com

In her preface to the 1965 edition of Conquest of Violence (see References at the end), Joan Bondurant makes a strong case for distinguishing nonviolent action as duragraha or Gandhian satyagraha. She argues that duragraha involves pressuring opponents based on a de facto prejudgment that they are wrong, through passive resistance, and through symbolic violence. In a later essay (posted previously here), she adds that it is a form of stubborn or willful resistance seeking to demonstrate that opponents are necessarily wrong; that resisters are inherently righteous; and that the purpose of nonviolent action is to gain predetermined objectives by winning battles with opponents. In contrast to satyagraha (i.e., firmness in seeking truth through the power of love), duragraha aims at gaining tangible concessions from power-holders in the short-term rather than transforming social relationships and creating in the long run alternative ways of life benefiting everyone, especially the most oppressed. Bondurant emphasizes these distinctions, because she feels that most of the so-called Gandhian struggles during the 1960s are actually examples of duragraha, not satyagraha. In her eyes, this misunderstanding severely limits the political, ethical, and transformative potential of these struggles.

In the 1960s, Gene Sharp—the undisputed pioneer of nonviolent action and civil resistance studies—responded very differently to Gandhi’s legacy. Unlike Bondurant, Sharp invokes Gandhi to define nonviolent action as “a technique used to control, combat and destroy the opponent’s power by nonviolent means of wielding power”, without carefully conceptualizing satyagraha or considering how it diverges from duragraha (Sharp 1973: 4). By erasing these differences, and by focusing on conventional power politics instead of situational ethics, his The Politics of Nonviolent Action articulates a generic and simplistic understanding of nonviolent action that applies to many cases of unarmed resistance throughout history and across the world. In the process, he normalizes duragraha as a pragmatic and strategic form of nonviolence, thereby hollowing out Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha while continuing to use Gandhi’s name to popularize his own approach. Since the 1970s, Sharp has quickly become the most influential figure in the field, serving as mentor to fellow civil resistance authors like George Lakey, Peter Ackerman, Jack Duvall, Michael Randle, Howard Clark, April Carter, and of course Mary King.

Read the rest of this article »

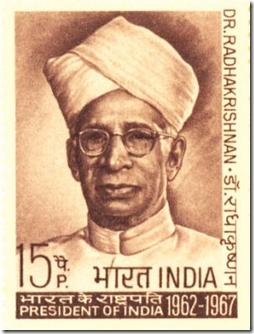

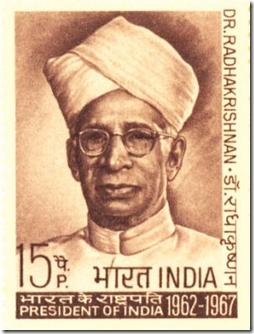

by Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Editor’s Preface: When Dr, Radhakrishnan wrote this essay in 1962 for the Gandhi National Memorial Fund, New Delhi he was the second President of India and one of India’s foremost contemporary philosophers. A relatively unknown essay, it is another in our series of discoveries from the War Resisters’ International archive. For an archival reference and biographical information about Dr. Radhakrishnan please see the notes at the end. JG

Indian commemorative postage stamp; courtesy librarykvpattom.wordpress.com

Many parts of the world are eagerly and enthusiastically awaiting the centenary of Gandhi [2 October 1969]. We here in India await it too. Though he belonged to the world, he also belongs to our country. As the London Times remarked: “No country other than India, and no religion other than Hinduism could have produced a Gandhi.” So he belongs to us in a very special sense. There are several ways in which he has worked for the country and the world. He was a great nationalist leader. He was a liberator of the enslaved. He taught the doctrine of a love that never fails. He was a moral genius who tried to chasten himself first before trying to exert any kind of influence on others. In all these ways he has helped us.

It is over thirty years ago that I put to Gandhi three questions: (1) What is your religion? (2) How are you led to it? (3) What is its bearing on life? He gave the following brief answers: “I used to say, ‘I believe in God’, now I say, ‘I believe in truth’. ‘God is truth’, that is what I am saying and today I say, ‘Truth is God’. There are people who deny God. There are no people who deny Truth. It is something which even the atheists admit.” Here he was not enunciating any new proposition. He was merely declaring fundamental truths that have come down to us from the environment in which he lived, the environment which nourished him. He took up two things. Speak the truth, do the right thing: truth and right action. He called them ‘Truth and Ahimsa’. These were his principles. Truth is not something we can casually work at. It requires considerable travail of the human spirit to cultivate harmony between the inward and the outward.

Read the rest of this article »

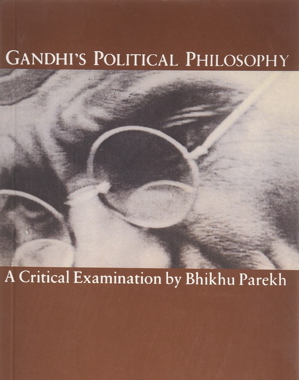

by Bhikhu Parekh

Dust jacket art courtesy Palgrave Macmillan; palgrave.com

Marxist interpretations of Gandhi contain important and valid insights that are, however, oversimplified; the picture is more complex and messy. The Congress under Gandhi’s leadership was not a party of the upper middle class. Although it did not reject the institution of private property, it assigned the State a considerable regulative and redistributive role, stressed the pursuit of social justice, and was not an advocate of unrestrained capitalism. To say, as some Marxists do, that since Congress did not advocate the abolition of the capitalist mode of production it was therefore a spokesman for capitalism, is to take too simple-minded a comment on the range of political possibilities open to radicals. Congress was essentially a middle class party, constantly reaching out to new groups and interests on both sides of the economic consensus in a way that was neither wholly capitalist nor fully socialist and not heavily biased towards a particular group. Rightwing and leftwing ideas grew up around its petit bourgeois core and both shaped and were in turn shaped by it. Nehru put the point well: “Even our more reactionary people are not so rigid in their reactions as they are probably in Europe and America. And even our most advanced people are somehow influenced by Gandhiji. He created connecting links between conflicting interests.”

The flow of political influence and the process of moral sensitisation between the different groups proceeded in both directions. The haute bourgeoisie influenced the Congress and enjoyed a measure of political power as the Marxists argue, but they were also required to recognise the legitimate demands of the poor and the oppressed. The middle and upper class peasantry did from time to time link up with the bourgeoisie, but it also retained its independence, threw up leaders of status and class loyalty, and influenced Congress policies on important matters. Many of these leaders were not created by or in any way indebted to the bourgeoisie, and had come to power on the basis of their personal sacrifices and leadership of peasant struggles. They had constituencies which they could not lightly ignore and whose interests they could not subordinate to those of some other class. The Marxist commentators exaggerate the situation when they claim that Gandhi delivered the peasantry to the capitalists.

Read the rest of this article »

by Nirmal Kumar Bose

Illustration art courtesy behance.net

Editor’s Preface: This article is the text of a speech delivered at the World Pacifist meeting in Shantiniketan, India, 1-5 December 1949, and continues our War Resisters’ International archive series. Nirmal Kumar Bose was an important figure in Gandhi’s life in the 1930s and 40s, and the author of an important diary of his life in Gandhi’s ashrams. For more biographical details please see the Editor’s Note at the end, along with an archive reference and a link to a pdf reproduction of the entire, original article. JG

India has tried to follow the principles of satya and ahimsa, truth and nonviolence, through centuries of her history. The actual application of these concepts has varied over the centuries and they have also been successfully employed in the solution of numerous problems relating to personal life or even group-life, where the group was based upon common religious experience.

Read the rest of this article »

by Purushottama Bilimoria

Indian actor Bagadehalli Basavaraju poses in classrooms as living statue of Gandhi; courtesy thebetterindia.com

Mohandas Karamchand [Mahatma] Gandhi adopted the metaphysics of a broadly-conceived Hindu religious thought for his social critique, out of which he developed a distinctive educational philosophy, which gave particular emphasis to truth and nonviolence, or the teaching of peace. In his social thinking he gave immense importance to what he called a ‘balanced’ form of education. By this he meant balanced as to needs, i.e. the necessities of life, against wants, i.e. whatever one yearns to possess, acquire or enjoy out of desire; and, more significantly, balanced as to internal values against a disproportionate concern with the externals (1948: 52). By ‘externals’ is meant the goods people generate and the sorts of activities, planning and manoeuvres people carry out in the normal course of living in order to meet the demands of commerce, material accessories, personal welfare and reproduction, and which are at the same time instrumental in sustaining the community.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Anti Iraq War protest, Washington, D.C., Sept. 15, 2007, courtesy Wikipedia.org

“We chose to be in the sights of the weapons of our own troops. For a few days, we were just as vulnerable as the Iraqi people. Explosions were occurring all over the city from missile attacks by our fleet in the Gulf.” Jim Douglass

Street Spirit: Gandhi referred to campaigns of nonviolent resistance as “satyagraha” — holding firmly to truth. What are the essential steps in building satyagraha campaigns, both in Gandhi’s era and in our time?

Jim Douglass: The most basic thing is the commitment of the people who seek to engage in such a campaign. There would have never been satyagraha campaigns in Gandhi’s life if he hadn’t created communities out of which they could be waged. The ashrams in South Africa and later in India were the bases of his work. And even though the number of people living in community and taking vows of nonviolence was small, those people were totally freed to work together and to respond to the specific evils they focused on. As Gandhi always taught, you can’t take on everything in the world, so you focus by identifying a social evil, as for example we did in the Trident campaign.

Read the rest of this article »