by John S. Moolakkattu

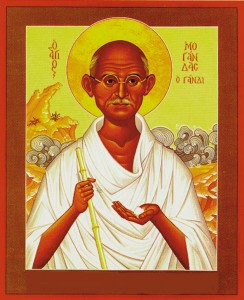

“Mohandas Gandhi of India”;

“Mohandas Gandhi of India”;

original icon by Robert Lentz;

thanks to Trinity Stores

Is Gandhi a human ecologist? If we go by the ideas generated by the environmental movement in India, which is strongly influenced by Gandhi, the answer is a definite ‘yes’. But Gandhi’s place in the ecological movement is yet to be established on a secure footing internationally. Even the recent Encyclopedia of Human Ecology edited by Julia R Miller et al. (2003) omitted Gandhi as one of its entries in its otherwise impressive list. Ecological consciousness, understandably, is a phenomenon that gained momentum only in the last four decades or so. But the roots of it can be traced to worldviews, traditions, culture, religion and folklore. Ecology is the science that focuses on the relationships between living organisms and their environment. Human ecology is about relationships between people and their environment. Human activities impact on ecosystems. Conversely, ecosystems are strongly influenced by the social system in which people live. Our worldview both as individuals and as society shapes the way we formulate our strategies for action (Marten 2001).

Read the rest of this article »

by C. E. M. Joad

In what consists the most characteristic quality of our species? Some would say, in moral virtue; some, in godliness; some, in courage; some, in the power of self-sacrifice. Aristotle found it in reason. It was by virtue of our reason that, he held, we were chiefly distinguished from the brutes. Aristotle’s answer gives, I suggest, part of the truth, but not the whole. The essence of reason lies in objectivity and detachment. It is reason’s pride to face reality, when the garment of make-believe, with which pious hands have hidden its uglier features, has been stripped away. In a word, the reasonable man is a man unafraid; unafraid to see things as they are, without weighing the scales in his own favour, allowing desire to dictate conclusion, or hope to masquerade as judgment.

The reasonable man, then, is detached: detached, that is to say, from the subject-matter which his reason investigates.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vandana Shiva

Gandhi on the Salt March, 1930.

In Hind Swaraj, Gandhi exhorts using ‘soul force’ as a means to seek ‘right livelihood’ – which is what real freedom is all about. Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj has, for me, been the best teaching on real freedom. It teaches the gospel of love in place of hate. It replaces violence with self-sacrifice. It puts ‘soul force’ against brute force. For Gandhi, slavery and violence were not just a consequence of imperialism: a deeper slavery and violence were intrinsic to industrialism, which Gandhi called “modern civilisation”.He identified modern civilisation as the real cause of loss of freedom. “Civilisation seeks to increase bodily comforts and it fails miserably even in doing so… This civilisation is such that one has only to be patient and it will be self-destroyed.”

Read the rest of this article »

Negley FARSON (Special Correspondent for India), The Chicago Daily News:

Bombay, June 21, 1930.

Heroic, bearded Sikhs, several with blood dripping from their mouths, refusing to move or even to draw their ‘kirpans’ (sacred swords) to defend themselves from the shower of lathi blows.

Hindu women and girls dressed in orange robes of sacrifice, flinging themselves on the bridles of horses and imploring mounted police not to strike male Congress volunteers, as they were Hindus themselves.

Stretcher-bearers waiting beside little islands of prostrate unflinching, immovable Satyagrahis, who had flung themselves on the ground grouped about their women upholding the flag of Swaraj (home-rule).

These were the scenes on the Maidan Esplanade, Bombay’s splendid seafront park, where the six-day deadlock between police and Mahatma Gandhi’s followers has broken out in a bewildering brutal and stupid yet heroic spectacle.

Read the rest of this article »

Webb MILLER (Special UP Correspondent for India), The New York World-Telegram, Dharasana Camp, Surat District, Bombay Presidency, May 22, 1930.

Amazing scenes were witnessed yesterday when more than 2,500 Gandhi ‘volunteers’ advanced against the salt pans here in defiance of police regulations. The official government version of the raid, issued today, stated that ‘from Congress sources it is estimated 170 sustained injuries, but only three or four were seriously hurt.’

About noon yesterday I visited the temporary hospital in the Congress camp and counted more than 200 injured lying in rows on the ground. I verified by personal observation that they were suffering injuries. Today even the British owned newspapers give the total number at 320 …

The scene at Dharasana during the raid was astonishing and baffling to the Western mind accustomed to see violence met by violence, to expect a blow to be returned and a fight result. During the morning I saw and heard hundreds of blows inflicted by the police, but saw not a single blow returned by the volunteers. So far as I could observe the volunteers implicitly obeyed Gandhi’s creed of non-violence. In no case did I see a volunteer even raise an arm to deflect the blows from lathis. There were no outcries from the beaten Swarajists, only groans after they had submitted to their beating.

Read the rest of this article »

by Étienne Balibar

The theme I shall address today has all the trappings of an academic exercise. Still, I would like to attempt to show how it intersects with several major historical, epistemological and ultimately political questions. As a basis for the discussion, I will posit that Lenin and Gandhi are the two greatest figures among revolutionary theorist–practitioners of the first half of the twentieth century, and that their similarities and contrasts constitute a privileged means of approach to the question of knowing what ‘being revolutionary’ meant precisely, or, if you prefer, what it meant to transform society, to transform the historical ‘world’, in the last century. This parallel is thus also a privileged means of approach to characterizing the concept of the political that we have inherited, and about which we ask in what senses it has already been and still needs to be transformed. Naturally, such an opening formulation – I was going to say, such an axiom – involves all sorts of presuppositions that are not self-evident. Certain of them will reappear and will be discussed along the way; others will require further justification. Allow me briefly to address several of them.

Read the rest of this article »

![]() “Mohandas Gandhi of India”;

“Mohandas Gandhi of India”;